Thanks to Mark Metcalf for scanning in this document and publishing it on his blog.

More material about resistance to the Poll Tax in Hackney can be found on this site here.

A PDF version of this pamphlet (and others by HCDA) is available here.

HACKNEY COMMUNITY DEFENCE ASSOCIATION

Set up in the summer of 1988, the Hackney Community Defence Association is a campaigning organisation which works in Hackney to challenge police attacks against the community. HCDA holds regular meetings on alternate Wednesdays, where all aspects of its work are discussed.

There are five main areas of HCDA’s work:

- Legal defence: HCDA takes up cases of people who have suffered police injustice.

- Police monitoring: HCDA monitors police activity in the area.

- Public events: HCDA engages in political activity by raising the issue of police injustice in the community.

- Para legal support: HCDA provides para-legal support to campaigns who are likely to find themselves in confrontation with the police.

- Community Defence: HCDA seeks to build confidence and strength within the community so that people can readily challenge police injustice.

If you want to learn more about HCDA write to HCDA, the Family Centre, 50 Rectory Road, London, N16 7QY. Or leave a message on the answerphone on 071-249 0193.

Cover photo by David Hoffman

Contents

I. Introduction

II. Background

III. Organisation of the demonstration

IV. Thursday March 8th

V. Arrests

VI. Not guilty

VII. Personal accounts

VIII. What the papers said

IX. Conclusion

A PEOPLES’ ACCOUNT OF THE HACKNEY ANTI-POLL TAX DEMONSTRATION ON MARCH 8TH 1990

INTRODUCTION

On Thursday March 8th 1990, Hackney Council met at the Town Hall to set its poll tax charge for the financial year 1990/91. The Hackney Against the Poll Tax Federation (HAPTF) organised a mass lobby of the meeting. An estimated 5,000 people attended the demonstration outside the Town Hall which developed into a confrontation between police and protesters with many people injured and 57 arrested. Inside the Town Hall Hackney Council set a poll tax charge of £499. It is normal practice for the Metropolitan Police to compile reports into public disorder incidents. Home Secretary, David Waddington, demanded an urgent Scotland Yard report into the Hackney disturbance the very next morning. However, such reports are specifically prepared to meet the state’s needs for the policing of public disorder, and are never made public. In all matters to do with policing it is important that the community, and its representative groups, compiles its own reports. This report has been compiled by Hackney Community Defence Association (HCDA) in association with some of the people arrested on March 8th.

BACKGROUND

I. Against the Poll Tax

The scale of opposition to the poll tax has taken many people by surprise. Who could have imagined Tory councillors resigning in protest against a Tory Tax? The opposition of working class people was expected, but few Labour councillors have taken such a principled stand.

The Labour Party’s refusal to organise demonstrations against the poll tax has led to the growth of an independent political campaign across the country. In the absence of any other form of organisation, an alliance has emerged which includes disillusioned Tory voters, left groups, and the dispossessed people of Britain. Resistance to the poll tax has been co-ordinated through a well orchestrated campaign of civil-disobedience; in Scotland many people have not paid a penny one year after its introduction. In England and Wales, where the tax has been introduced one year later, many have declared their intention not to pay.

The campaign has united sections of the population who have very different ways of protesting against unpopular measures. After a decade of high unemployment, the replacing of social security with harder to get income support and widespread cuts in public services, there are many people who believe they now have little to lose by all-out confrontation.

Public demonstrations against the poll tax have drawn together on the streets those people opposed to the tax in principle, because it is unfair and infringes on civil liberties, and those who see the poverty which the tax imposes as the last straw. Both sections of the population are equally determined to express their opposition to the tax. A long tradition of free speech and the right to protest is being continued.

The poll tax directly affects council workers and members of the community who rely on the services provided. Many councils have had to make widespread cuts in order to keep poll tax bills down. Hackney Council’s poll tax rate of £499 includes £10 million cuts in services; these include the closing down of the George Sylvester Sports Centre and of the Media Resources Centre, 100 redundancies as a result of a 15% cut in grants to the voluntary sector, and cuts in education, social services and environmental services.

On the other hand, the poll tax is far more expensive to administrate than the old rates system. Thus money is being taken away from services to implement the tax, provoking outrage among council workers and members of the community affected.

It is important to stress that broad sections of the population have not suddenly’ raised their voices against one unpopular piece of government legislation. Since 1977, when the Labour Government commenced making public expenditure cuts, the welfare state has been under consistent attack. At issue is not simply how local services are to be paid for, but whether the welfare state itself is going to survive into the twenty first century. In effect the poll tax summarises over a decade of Thatcherite attacks against the working class.

II. Living in Hackney

Radical history

Hackney has a radical tradition which matches its poverty and deprivation. This radicalism has not been significantly based in the Labour Movement, primarily because the area is not a home to any large scale industry. However, on issues which transcend purely economic affairs, Hackney has been in the forefront of political struggles. Three of the most important mass movements this century have been strongly based in Hackney and the East End of London – the Suffragettes, the Communist Party and the anti-fascist movement. It should therefore come as no surprise to discover a strength of feeling and determination against the poll tax in Hackney.

Unemployment/employment

Hackney is generally recognised as one of the poorest boroughs in Britain, enduring unemployment rates far higher than the national average. In the four years 1984 – 87, when statistics bore some resemblance to reality, over one in five of the working population was registered unemployed, more than double the national average. The largest employer in Hackney is Hackney Council. On December 1st 1988 it had a workforce of 8,619. All of these jobs have been threatened by rate capping in recent years, and now by the poll tax. A quick glance at the Department of Employment’s statistics for 1986 shows that out of 75,302 jobs in Hackney. 36,771 (49%) were in local government, transport, construction, distributive trades, and clothing manufacture, all low paid jobs. Only 2,575 (3.5%) worked in the higher paid engineering industry, and despite its proximity to the City of London and the new yuppie paradise docklands area, only 5,009 (6.6%) jobs existed in finance, banking and insurance.

Housing

Hackney suffers from homelessness, poor housing stock and inadequate back up services. Alongside the large council housing estates Hackney has a large private rented Sector (18.7% in 1981 compared to a national average of 11%), which is notorious for poor quality. In 1987 Hackney Council investigated 1,670 new cases of homelessness. This figure does not include the many ‘homeless’ people living in squatted accommodation. With recent estimates putting the number of squatted properties at 3,500, Hackney contains the largest squatter community in the country.

Out of 46,072 council properties in 1988, 13,450 (29.2%) were considered to be in an unsatisfactory state (i.e., properties which are either unfit for living in, or lack basic amenities, or in need of basic repairs). Private sector stock is generally older than the post war council stock and council estimates suggest that over half (6,000 homes) are in an unsatisfactory condition.

Alongside the imposition of the poll tax, council tenants have seen their rents, excluding the old rates, increase by about double the rate of inflation. Private tenants have not generally had their rents reduced to take the Poll Tax into account and therefore have to find an extra £41.58 a month per member of household.

Health

A recent report by the City and Hackney Health Authority entitled “Health in Hackney” found that the local population is “suffering from “poverty and multiple disadvantages”.

The report, which was published soon after the announcement that a planned extension to the Homerton Hospital would not go ahead, disclosed high levels of food poisoning, heart disease, tuberculosis, and one in six smoking related deaths.

Race

Over half of Hackney’s population is made up of people of non-British descent. It has become far too easily accepted that black and ethnic minority Communities suffer the highest levels of unemployment, work in the lowest paid jobs, live in the worst housing conditions, and suffer a high frequency of police harassment.

Policing

Hackney police have built up national notoriety in the past 20 years for brutality and racism. Since the death of Aseta Simms in Stoke Newington police station in 1971, there have been five other suspicious deaths in Hackney’s police stations, including the shooting of Colin Roach in 1983.

There have also been a growing number of reports of cases of brutality and misconduct, including the well reported case of Trevor Monerville in 1987. Police oppression has been met by determined resistance. Throughout the eighties there was a succession of community campaigns which culminated in the setting up of the Hackney Community Defence Association in the summer of 1988.

As in other inner city areas the police in Hackney have increasingly concerned themselves with public order policing. More and more, the police have acted as a force engaged in social control, rather than crime control. They have taken every opportunity to destroy any growing sense of community by criminalising sections of the population and closing down public meeting places.

As in Brixton and Notting Hill, black people and their pubs, clubs and cafes have specifically been targeted. In August 1988, 200 police sealed off the Clapton Park estate while the home of a community leader was raided under the pretext of looking for drugs. Two weeks earlier the home of another community leader on the estate had been raided without a search warrant. Armed police raids against black clubs, with press photographers in tow, took place on several occasions in 1988. These raids were linked to much media hype about Jamaican ‘Yardie’ gangs.

The Turkish and Kurdish communities have been subjected to police immigration raids throughout the years. After 37 people were arrested following such a raid in February 1989, 5,000 people, mainly Turkish and Kurdish refugees, took to the streets in protest.

The police have also singled out squatters and their meeting places for harassment. In 1986 the Three Crowns public house in Stoke Newington was forced to close after a series of violent police raids. In 1988 a community centre set up by squatters on Northwold Road, N16, was closed down by the police. In the last two years the Cricketers pub has been subjected to regular police raids. On one occasion, a Territorial Support Group unit entered the pub and ordered people to leave. Outside in the street more police officers started to abuse the people on their way home, and one person was viciously assaulted. The Stamford Hill estate in Stoke Newington developed into a squatting centre with over 120 flats squatted. In the spring of 1988 Hackney Council, needing to defend a failing housing policy, decided to renege on its non-eviction policy and announced that there was to be a mass eviction.

Squatters put up determined resistance by barricading the estate against bailiffs and police. It was only when riot police charged the estate that the council successfully evicted the squatters.

Over the years Hackney has seen many public demonstrations. The marches following Colin Roach’s death in 1983 were attacked by the police leaving many people injured and arrested. More recently, the police adopted heavy handed tactics against the Third Annual “We Remember” Commemoration, held in January 1990.

Demonstrations covering a broad range of issues, from immigration raids to support for the ambulance drivers, have been heavily policed in attempts to intimidate protesters and criminalise protest. Based on these experiences the community’s expectations of the police at demonstrations is that there will be far too many in attendance, and they will behave in an aggressive manner.

III. A week of demonstrations against the Poll Tax

On Monday March 5th, Haringey Council met at the Civic Centre to set its poll tax rate. A demonstration of some 500 people disrupted the meeting and caused it to be abandoned, there were 13 arrests. Throughout the week mass demonstrations against the poll tax across England and Wales featured on TV news programmes and in the press. The media focused on the confrontations between protesters and police, highlighting the numbers of injuries and arrests.

By the time the early evening TV news on Thursday March 8th reported that Hackney Council was about to set its poll tax rate, a large crowd had already assembled outside Hackney Town Hall. Hackney’s radical history, the prevailing economic conditions, a long standing breakdown in police community relations, and the gathering momentum of a nationwide campaign against the poll tax, seemed to make it inevitable that a confrontation would follow.

ORGANISATION OF THE MASS LOBBY

I. Hackney Against the Poll Tax Federation

The Hackney Against the Poll Tax Federation (HAPTF) is affiliated to the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation. Its principal role is to co-ordinate the activities of the Anti-Poll Tax Unions which have been organised on Hackney’s housing estates. The unions’ work is devoted to preparing for the non-payment campaign, and mobilising support for demonstrations against the poll tax.

II. HAPTF preparations

The HAPTF’s main concern in organising the mass lobby of Hackney town Hall was to get people to attend. Posters were fly-posted and leaflets distributed around Hackney by the Federation and local Anti-Poll Tax Unions.

The HAPTF did not pay any attention to the stewarding of the demonstration, nor did they prepare any contingency plans in readiness for confrontation between police and protesters. The HAPTF did not have any stewards at the demonstration who might have controlled the situation at the outset, or help people who might get caught up in any violence. As well as the HAPTF, other organisations mobilised for the mass lobby. Most Importantly the Joint Shop Stewards Committee (JSSC), consisting of the main council unions, distributed leaflets advertising the event. The JSSC agreed to provide a public address system for a rally to be held outside the Town Hall. Speakers at the rally were to include representatives from the HAPTF, Anti-Poll Tax Unions and trade unionists.

Ill. HCDA preparations

Although not ‘officially’ approached by any of the organisers, HCDA recognised the potential for confrontation and arrests two days prior to the event. Four solicitors were contacted and asked to be on standby for the evening of March 8th to represent persons arrested. 2,500 bust cards were produced giving protesters information on what to do if arrested, a telephone number to call, and an appeal for witnesses. 500 bust cards were left at the Mare Street NALGO office for distribution among the council unions. Two photographers were contacted to take photographs of people being arrested.

THURSDAY MARCH 8TH

I. Chronology of events

The times given in this chronology of events are all approximate. Because the situation developed very quickly, and many incidents took place at similar times, we have kept to 15 minute intervals to outline what took place. After the first arrest in front of the Town Hall, at approximately 7.15pm, 57 arrests were made. Numerous police charges and sporadic fighting took place throughout the mid-late evening, and many missiles were thrown at the police. The demonstration was effectively over by 9.30pm, although isolated incidents continued late into the night.

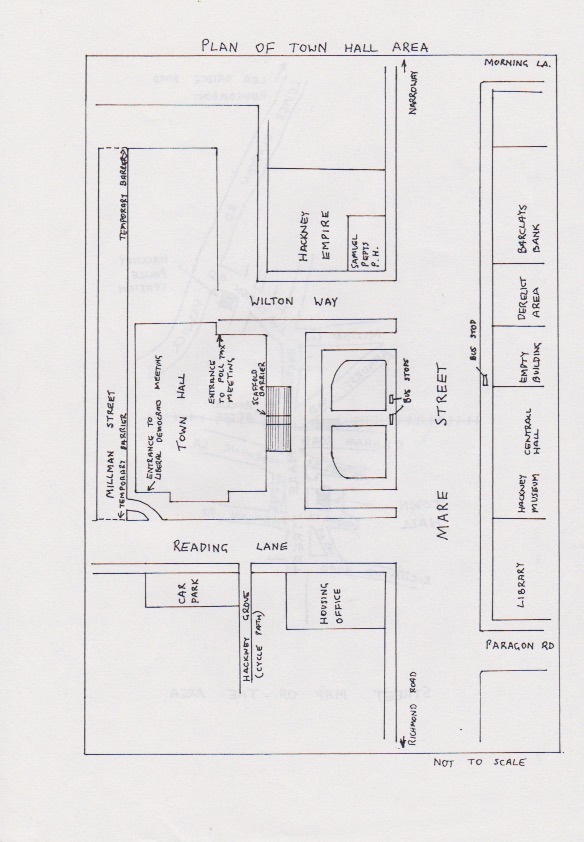

6.00pm People begin to assemble outside Hackney Town Hall, about 200 present. The lower windows of the building and those of the Housing Office in Reading Lane have been boarded up. A private security firm Is patrolling the inside of the Town Hall with dogs. A scaffolding barrier has been erected by the council on the steps to the main entrance of the Town Hall forming a narrow passageway up the steps. At the foot of the steps in front of this passageway 10-15 police officers are situated under the command of a superintendent, a few police officers are at the top of the steps by the main doors. Plain clothes police are also in evidence on the steps, outside the barriers, and on Wilton Way beside the Hackney Empire.

Police officers are much in evidence around the building. The police headquarters is behind barriers cordoning off both ends of Hillman Street behind the Town Hall. Green buses containing police reinforcements are parked in this area along with many police vans. Barriers guarded by police officers. The HAPTF is setting up a stall directly opposite the Town Hall steps. Militant has a stall on the right hand side of the square facing the building. HCDA members are distributing bust cards. Many of the demonstrators are handing out leaflets to passers by on Mare Street.

Police tell the organisers that 25 people will be allowed into the Council Chamber public gallery to hear the poll tax debate. In the Assembly Hall at the side of the town Hall, 200 people are to be allowed into the Liberal Democrat’s public meeting at which Paddy Ashdown is speaking.

6.30pm About 700 people present. The Joint Shop Stewards Committee falls to provide a public address system, and HAPTF members discuss whether to commence the rally with a stand-in megaphone. A contingent of Socialist Workers Party arrives and takes up a position directly opposite the police facing the Town Hall steps on the other side of the service road. SWP placards against the Poll Tax are handed out to demonstrators. Demonstrators begin to chant slogans against Thatcher (“Maggie, Maggie, Maggie – Out. Out, Out”) and against the poll tax (“No Poll Tax, No Poll Tax, No Poll Tax,…”). In the fading light TV arc lights are turned on and directed at the crowd.

6.45pm About 1500 people present. Large numbers of anarchists/squatters begin to arrive and take up positions directly opposite the police lines, and in front of the SWP contingent. A small number of people in this section of the crowd appear to be drunk and carrying cans of beer. The HAPTF attempts to hold their rally from the Town Hall steps.

Due to the absence of an effective PA system the speeches are inaudible beyond a limited area. After a couple of speeches the rally is abandoned.

7.00pm The crowd quickly swells to about 3,500. The make up of the demonstration is predominantly white, with equal numbers of men and women. There is a lot of pushing and shoving, and a few missiles are thrown at the police, mainly fruit and empty cans, by people directly in front of the police lines. The odd bottle and heavier missiles are thrown from towards the rear of the crowd. A line of Territorial Support Group (TSG/riot police) officers. wearing flat caps, forms up in front of the Town Hall steps.

7.15pm About 4,000 people present and the crowd still growing. The Town Hall steps are packed with people. The densest part of the crowd is standing on the right hand side (facing the Town Hall). A lot of pushing and shoving in front of the Town Hall and more missiles are openly thrown at the police by people in the front of the crowd. Protesters chant at the police “Out of the way”. A significant number of people, about 1500, are standing on the grass in the square opposite the Town Hall. The first arrest takes place. Two police officers from the steps, one in the front line and one free standing on the steps, arrest a white male from the left hand side (facing the Town Hall). He is dragged by police to a van parked in Reading Lane. Abuse is hurled at the police in response to the arrest. A short while later there is a big surge by the crowd and more arrests take place. Protesters are arrested trying to help others who have already been arrested. Some protesters run from the fighting and others run towards the fighting. By 7.30pm more and more missiles are being thrown at the police including a few small smoke bombs and flour bombs. the power on the TV arc lights is increased, illuminating the whole area in front of the Town Hall.

7.30pm 4,500 to 5,000 people present. For a short moment there is an eerie kind of silence before hand to hand fighting breaks out between police and protesters on the left hand side (facing the Town Hall) in front of the steps. Police officers hold their ground on the steps and more people are arrested. Officers who enter the crowd suffer violence when they get cut off from the police lines. A protester climbs onto the balcony above the main entrance facing the square. He is handed a large banner saying “Pay no Poll Tax” and is warmly cheered by the crowd. He stays on the balcony for about 30 minutes coming down just after 8.00pm.

7.45pm There is a concerted effort by demonstrators to overrun police lines and gain access to the building through the main entrance. The police maintain their position and skirmishes follow at the foot of the steps.

The focus of the demonstration begins to shift away from the main entrance to Reading Lane. Some protesters follow the police and arrested persons, and fighting continues.

Liberal Democrat leader Paddy Ashdown is shouted down by the crowd as he is interviewed by TV news. About 200 people try to force their way into the Liberal Democrat’s meeting. Police reinforcements come from the rear of the. Town Hall and form a cordon across the entrance to the meeting. The situation calms down and police let people into the meeting. About 100 demonstrators enter the meeting with the people going to hear Paddy Ashdown speak. There is no attempt to disrupt the meeting but protesters try to go from the hall through to where the council meeting is taking place in the Council Chamber. They are chased out of the Town Hall by security guards with dogs, and police move into the meeting to throw out protesters. There are no arrests at this stage. Town Hall windows are broken by demonstrators in Reading Lane. Police press protestors up against the car park fence, forcing many to retreat over the fence into the car park.

A convoy of about 10 TSG vans arrives and moves into Reading Lane from Mare Street. Demonstrators and bystanders standing on Reading Lane by the Housing Office scatter as the vans arrive. 40-50 riot police form a cordon across Reading Lane in front of the side entrance to the Town Hall. Some TSG vans remain parked on Mare Street and some riot police move into the area facing the Town Hall.

8.00pm There is a big push by about 400 people towards the entrance of the Liberal Democrats’ meeting. Many of these people have moved from the fighting in front of the Town Hall. They are met by the police cordon. At this time there is a change of mood among protesters who become more actively anti-police. About 200 demonstrators fight with police. An industrial refuse bin is turned over and rolled towards the police line, and a road traffic sign is used as a makeshift battering ram. The police retreat down Reading Lane and regroup by entrance to Liberal Democrat’s meeting. Police then make a few small charges.

Police from behind the Town Hall charge demonstrators standing by the entrance to the Liberal Democrats’ public meeting. Police dogs move into the car park and demonstrators climb the fence and escape down cycle path towards Richmond Road. Missiles are thrown at police throughout this period.

8.15pm Until this point the police had on the whole soaked up a section of the crowd’s violence against them with remarkable restraint. However, the increased involvement of the TSG unleashed a police assault on the whole demonstration with indiscriminate attacks and arrests.

Riot police in Reading Lane draw truncheons and charge into the crowd. At the corner of the Town Hall the police line breaks up as police charge down Reading Lane towards Mare Street, and across in front of the Town Hall into the square. Bystanders on the periphery of the demonstration, including families and the elderly, are caught up in the police charge. Police do not appear to make any arrests, but single out demonstrators by lashing out with their truncheons. Many people are screaming and some push-chairs are overturned by the charging police.

Demonstrators spill onto Mare Street and a conscious decision is made to bring the traffic to a standstill. About 40 of the 800 demonstrators in the road sit down. There are about 2,000 people in the Mare Street area, in the road and on the pavements opposite the Town Hall. The character of the demonstration changes. Many of the original protesters leave and are replaced by younger people. A motorcyclist is knocked off his bike. The crowd parts to allow an ambulance through Mare Street and cheers the crew.

8.30pm Glenys Kinnock arrives for International Women’s Day festival at the Hackney Empire in Mare Street. About 12 demonstrators, some masked, surround her car, hurling abuse and kicking the car.

Police charge along Wilton Way from the Town Hall to Mare Street. As they reach Mare Street they meet the main body of the demonstration which repulses the charge. For a brief moment the police appear to lose control of the situation. Demonstrators chase the police back down Wilton Way. Police re-group, draw truncheons and charge at the demonstrators who scatter.

8.45pm Demonstrators throw bricks and debris at police lines in Mare Street from behind a fence enclosing a derelict area. About 70 police clear Town Hall square and drive a wedge into the demonstration on Mare Street opposite the Town Hall. Police block Mare Street by Richmond Road, then after 10 – 15 minutes appear to realise it is a tactical mistake.

Scuffles continue between police and protesters in Mare Street opposite the Town Hall. Police begin to move people away from Town Hall area in the direction of the Narroway.

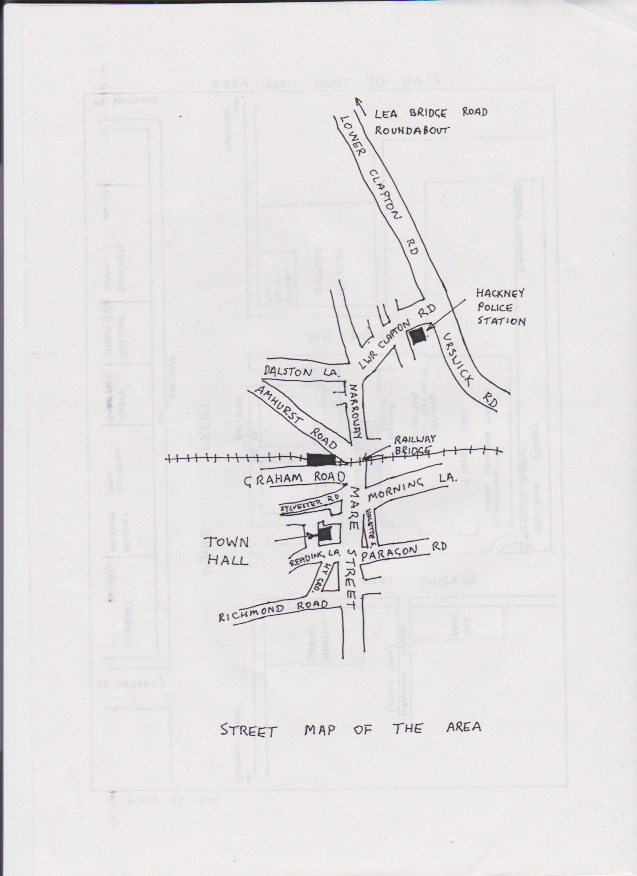

Groups 30-40 strong converge on Morning Lane to make a crowd 100 strong. The crowd moves down Morning Lane onto Mare Street, causing the police to back off. The crowd turns right into Mare Street and tears up paving stones to smash shop windows. Joined by more demonstrators to make up a total of about 200, they enter the Narroway and more shop windows are smashed.

9.00pm Although many people remain in Mare Street opposite the Town Hall, the poll tax protest is drawing to a close. more arrests are made as people resist police attempts to end the protest. Protesters cordoned off by police near the library are unaware of the situation developing in the Narroway.

200 strong crowd in groups of 10-15 move through the Narroway smashing the windows of business premises and setting fire to litter bins. The crowd moves through the Narroway very quickly, there is not much looting, as protesters concentrate on causing damage. At the end of the Narroway some people return in the direction of the Town Hall; about 100 move up Lower Clapton Road in the direction of Hackney police station and continue to damage some shops.

A brick is dropped on a woman police officer from the railway bridge over Mare Street.

9.15pm Police arrive in the Narroway.

About 75 people in small groups converge on Hackney police station. Windows are smashed and police lock the main entrance. A police car speeds round the corner and stops outside the police station. One PC and a WPC get out of the car and run towards the police station. They then turn round and run back up Lower Clapton Road where they are surrounded and attacked by demonstrators. The empty police car is overturned.

About 12 mounted police come out of the police station and charge up Lower Clapton Road in the direction of the Lea Bridge roundabout.

Although batons are drawn the police do not appear to use them. The police return along Lower Clapton Road at a trot harassing bystanders and people who have come out of the pubs to watch.

9.30pm Police reinforcements arrive, by which time it is all over apart from a few isolated incidents.

II. Emergency legal cover

Throughout the evening of March 8th, from 7.00pm until 3.00am the next morning, HCDA volunteers answered telephone enquiries and arranged solicitors for those people arrested. The first notification of an arrest came at 7.55pm from the duty sergeant at City Road police station, followed by another call at 8.15pm. No further calls reached HCDA from City Road police station. HCDA received one call from the duty sergeant at Leman Street police station. HCDA subsequently learnt that defendants were being told by the police that HCDA’s phone had been disconnected because the phone bill had not been paid – thus defendants were denied their right to make a phone call.

Between 11.00pm and 2.00am HCDA volunteers attended City Road and Leman Street police stations and telephoned through details of persons arrested so that they could be put in contact with solicitors. HCDA volunteers also visited Homerton Hospital to advise any injured persons who might be arrested at the hospital.

ARRESTS

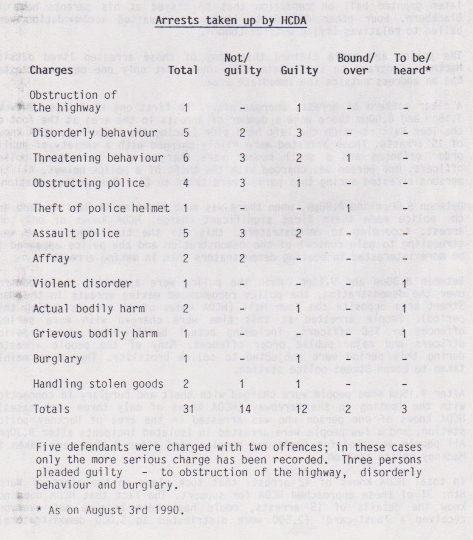

I. Overview

According to police figures, 57 people were arrested on the evening of March 8th. Nine people appeared at Old Street Magistrates Court on the morning of March 10th. At those hearings three persons pleaded guilty to offences and were severely dealt with by the magistrates. One man pleaded guilty to affray (throwing tomatoes), and was ordered to go to an attendance centre for 36 hours (he has since been arrested again for involvement in the Lambeth poll tax demonstration despite the fact that he was not there); another defendant was fined £250 for spitting on a policeman’s back; another was fined £50 for disorderly behaviour.

Six defendants pleaded not guilty to a variety of public order offences. One person charged with assault, criminal damage and disorderly conduct was remanded in custody. His solicitor appealed against the decision and he was later granted bail on condition that he stayed at his parents home in Blackburn. Four other defendants living in squatted accommodation were bailed to relatives living outside London.

The police and media claimed that many of those arrested lived outside Hackney. Contrary to this claim HCDA found that only one person arrested had do address outside the immediate area.

A clear pattern of arrests emerges after the first one at 7.15pm. Between 7.15pm and 8.00pm there were a number of arrests in the area at the foot of the Town Hall steps on the left hand side (facing the building), HCDA knows of 15 arrests. Those arrested were mainly charged with a variety of public order offences and a small number were charged with assaulting police officers, one person was charged with the theft of a police helmet. All the persons arrested during this period were taken to City Road police station.

Between 8.00pm and 8.30pm, when there was much fighting in Reading Lane and the police made their first significant charge, HCDA knows of only one arrest. According to demonstrators, this was the time when police were struggling to gain control of the demonstration and the police appeared to be more interested in beating demonstrators than in making arrests.

Between 8.30pm and 9.15pm, when the police were asserting their control over the demonstration, the police recommenced making arrests in the Mare Street area opposite the Town Hall (HCDA knows of 14 arrests during this period). People arrested at this time were charged with more serious offences by TSG officers, including actual bodily harm against police officers and major public order offences. Many of the people arrested during this period were subjected to police brutality. They were mainly taken to Leman Street police station.

After 9.15pm some people were charged with theft and burglary in connection with the looting in the Narroway (HCDA knows of only three such cases). HCDA knows of one person who was arrested in the area of Hackney police station, and a few people were arrested in isolated incidents after 9.30pm. All people arrested for theft and burglary and after 9.15pm were taken to Hackney police station.

In total HCDA knows of 42 arrests that took place on the night of March 8th; 31 of these approached HCDA for support. The fact that HCDA does not know the details of 15 arrests, could have been because not everyone received a ‘bust-card’ (2,500 were distributed to 5,000 demonstrators).

However, it is more likely that the majority of unaccounted arrests were of those accused of looting which, according to our information, was carried out by people unconnected with the demonstration. Those persons were unlikely to have had any information concerning HCDA.

Out of the 31 people who contacted IICDA, 28 pleaded not guilty to their charges. By August 3rd, 25 of these cases had been heard resulting in 14 acquittals, nine convictions and two bind overs. Two persons, Russell Duxbury and Neil Harding, received prison sentences. Russel Duxbury was convicted of assaulting a police officer at Old Street Magistrates Court on May 22nd and received a three month prison sentence in addition to a three month suspended sentence for a previous offence. His release date from Pentonville prison is August 8th 1990. Neil Harding received a 12 month prison sentence for affray (see below) at the Inner London Sessions House on July 23rd. At the time of writing he is being held in Brixton Prison. Gill Rogers was convicted of assaulting a police officer (see below) at Old Street Magistrates Court and received a 28 days suspended prison sentence.

II. Three cases

Below we briefly describe three cases of people arrested at the demonstration.

Gill Rogers

Gill Rogers and her four children live in Hackney. On Thursday March 8th she went with her 18 year old daughter, Kelly, to Hackney Town Hall to protest against the poll tax. She didn’t go looking for trouble, and told her neighbour, with whom she left her other children, that they would be home by nine o’clock.

Gill and Kelly arrived at the Town Hall at 6.45pm and joined the crowd in front of the building chanting slogans against the poll tax. Gill felt it was a good natured protest and did not see any trouble from where she and Kelly were standing.

Some time after 8.00pm, Gill and Kelly were ready to go home and started walking across Mare Street towards the library. Some people were sitting down in the road, and the traffic was at a standstill. They lingered briefly to see what was going on, and were moved down the road by two policemen along with other demonstrators.

Suddenly, a policeman grabbed Gill, and another took hold of Kelly, and frogmarched them down the road in the opposite direction to which they were going. Gill heard Kelly call out to her. She looked round and saw a policeman twisting Kelly’s arm up behind her back and, with his other hand, digging her repeatedly in the kidneys. Naturally distressed at this sight, Gill moved towards her daughter, trying to get between Kelly and the policeman. Gill was immediately swamped under a sea of blue uniforms, and was held by three or four police officers in a doubled up position. She managed to take hold of Kelly’s hand, who was crying, and told her to leave her and go home. Gill was then dragged off to a nearby police van.

After a while Gill was joined in the van by a young man who had been arrested and the vehicle sped off to City Road police station, getting lost on the way. At the police station Gill objected to having her fingerprints taken before she was informed that the police have the right to do this under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act.

At 12 midnight Gill was charged with assaulting a police officer; the police claimed that she hit a police officer around the head three or four times. She was eventually let out of City Road police station at about 12.30am having spent more than three hours in custody.

On Thursday July 5th 1990, Gill Rogers appeared at Old Street Magistrates Court and was found guilty of assaulting a police officer. She was given a 28 days suspended prison sentence and ordered to pay £25 costs.

Kate Millson

Kate Millson lives in Hackney and works in a centre for the unemployed in South London. An active trade unionist all her working life, she went to Hackney Town Hall on March 8th to protest against the poll tax.

Kate arrived at the Town Hall at 6.10pm and went to stand on the steps to the front entrance. She witnessed people getting arrested in front of the Town Hall some time after 7.00pm and was quite concerned for their welfare.

Despite the trouble that was going on around her, Kate was determined to remain outside the Town. Hall and maintain her right to demonstrate peacefully.

At about 8.30pm Kate was in Mare Street along with many other demonstrators. All of a sudden she was swept along with the crowd running down Mare Street towards the Hackney Empire, she stepped aside at the junction with Wilton Way and stood on the corner.

At this time police officers drew their truncheons and charged into the crowd along Wilton Way from the Town Hall towards Mare Street. Right beside where Kate was standing three women fell over one another as they tried to escape the violence. A policeman running past hit one of the young women on the head with a great deal of force with his truncheon. Kate helped the woman up and asked her if she was alright. A police officer then told her “mind your own fucking business”, to which Kate retorted “it is my business”.

The police officer began pushing Kate towards Morning Lane telling her to go home. She was angry at the way in which she was being treated and said “I am 38 years old and do not need to be told when I have to go home.”

The police officer continued to push Kate and pulled her suede jacket causing it to tear. Eventually, he let go of her jacket and she was able to see the amount of damage caused. She then asked him for his number, which she could not see in the poor light, saying that she would be making a complaint and seeking compensation. At this point the police officer said “You want my number? You can have it, you’re nicked.”

Kate was then handcuffed by the police officer and with another officer led to a police van in Wilton Way. She waited in the van for 15 to 20 minutes while other people were arrested before being taken to Leman Street police station.

At the police station the officer who arrested Kate could not be found, so she was left sitting on a bench, still handcuffed. She thought her period had started and asked what she should do if she needed to go to the toilet. To this an officer replied, “You say ‘please may I go to the toilet'”. When Kate said she thought she had started to menstruate and needed sanitary protection the police officers were quite embarrassed, released her handcuffs, provided her with a sanitary towel and escorted her to the toilet.

Eventually a black police officer came into the custody room and Kate was informed that he was her arresting officer. Kate said this could not be true as the police officer who arrested her was white and clean shaven, and this officer was black and had a moustache.

The black officer then proceeded to inform Kate that she had shouted out “You fascist bastard” at a police officer on the steps of the Town Hall. She was charged with threatening behaviour. Having been held in police custody for over three and a half hours Kate was released at 12.30am. She had been refused her right to make a phone call, and had her photograph and fingerprints taken.

When Kate attended Old Street Magistrates Court on March 29th the additional charge of assaulting a police officer was brought against her.

At Old Street Magistrates Court on Monday May 14th, Kate Millson was found guilty of threatening behaviour and assaulting a police officer, despite the existence of photographic evidence which contradicted the police story.

She was fined £50 for each charge.

Kate Milison appealed against the guilty verdicts. At Kennington Crown Court on Thursday August 3rd she won her appeal overturning the magistrate’s decision. She is now preparing to take out a civil action against the Metropolitan Police.

Neil Harding

Neil Harding has lived in Hackney for seven years. He recently began a business enterprise scheme to set up his own music publication business. A week before March 8th, Neil pulled a muscle in his back which caused him much pain and restricted his movement. On Thursday March 8th at about 8.10pm he decided to go to the anti-poll tax demonstration.

Neil walked down the cycle path joining Reading Lane to Richmond Road, to find police and protesters fighting beside the Town Hall. He stayed and watched for some minutes before walking back along the cycle path and up Richmond Road to Mare Street, and then to a place opposite the Town Hall. By the time Neil reached Mare Street protesters had blocked the traffic. He chatted briefly to some friends at about 8.45pm. There were many people in the area and missiles were being thrown at a line of about 30 police officers who stood facing Mare Street in front of the Town Hall square.

Neil heard somebody near him shout “Police!”, and everybody around him scattered. Because of the injury to his back, Neil could not run and stood his ground to face a police officer running in his direction. He expected the officer to continue running past him, after the people who had been throwing missiles. Instead, the police officer shouted out to Neil that he was under arrest. Neil did not move, and made no attempt to resist arrest.

The police officer took hold of the sweat shirt Neil was wearing, and in one movement, threw him head first into a bus shelter, causing him to fall to the ground. The officer then held him on the ground.

Other protesters came forward to try and rescue Neil. One attempted to push the police officer away from him, and another took hold of him under the arms and tried to pull him upright. A woman police officer quickly arrived on the scene and pushed the other protesters away. Neil was again pinned down in the gutter, with the arresting officer’s knee forced into his stomach, and his left hand around his throat. With his free hand the police officer radioed for assistance.

When police reinforcements arrived Neil was dragged to his feet and marched across the Town Hall square, which the police had cleared of protesters, to a police van.

At Leman Street police station Neil was charged with affray, being accused of throwing bricks and debris at the police, and causing actual bodily harm to a police officer.

On Monday July 23rd 1990 Neil Harding was found guilty of affray and actual bodily harm at the Inner London Sessions House. He was sentenced to 12 months imprisonment.

NOT GUILTY

On Friday July 27th 1990, Chas Loft was acquitted of affray at the Inner London Sessions House. The jury took less than half an hour to reach a unanimous verdict. This is Chas Loft’s story.

On March 8th I went to the anti-poll tax demonstration at Hackney Town Hall. I was looking forward to it as I knew there would be a good turn-out. When I arrived I was surprised to see a large number of police on the Town Hall steps, and the Town Hall was boarded up. These two things suggested that the ‘authorities’ had adopted a confrontational attitude to the protest.

I spent the next hour wandering around the Town Hall square looking for friends and joining in the chanting. There was a good atmosphere Of defiance and strength among the crowd with all kinds of people present.

At about 7.20pm I joined the crowd in front of the Town Hall steps. It was like being at the front of a packed gig, with little freedom of movement and sudden waves of pushing and shoving. When I got to the front I saw a policeman shouting “come on then” at the crowd, he was very threatening, beckoning us with clenched fists. Further along the line a policeman was holding a woman by the hair and punching her repeatedly in the face. These were officers from the TSG, identified by their flat caps.

Until I went on this demonstration I thought I had no illusions about the police. But when I actually got to the front of the crowd and saw how violent they were, I was frightened. As I turned to get away from the scene I was grabbed by one of the TSG. Someone tried to pull me away from him and I ended up on the ground. As I was getting up I heard someone say “get this one”, and I was grabbed and dragged away towards Reading Lane. At this point I was amazed rather than frightened at what was happening to me. I was not surprised that the police were arresting people for no reason, but I couldn’t believe it was happening to me. I started shouting “I haven’t done anything” and someone shouted “it’s alright, I’ve got photos”, which didn’t seem much use to me at the time.

I was put in a police carrier in Reading Lane and a police sergeant told me that I had been arrested for shouting, swearing and kicking a police officer; it was as if he was reciting a mental list. I was made to sit at the back of the van next to the police officer who had arrested me. When I complained that I’d done nothing, he said that he was going to take me to a closed van and give me a “fucking good kicking”. When we arrived at City Road police station the same officer told the desk sergeant to hurry up because he wanted “to get back to the fun.”

The time I spent in the police station was pretty uneventful. I was held in an an unlit cell for about four hours before being charged and released.

My first court appearance was very frightening because until then I did not know what I was supposed to have done. It was only when I read the police statements, and saw that I was supposed to have lashed out at police officers and kicked one, that I realised I was in serious trouble.

Some time after this I attended an HCDA meeting for March 8th defendants. I was shown photographs taken by HCDA of my arrest and began to realise the significance of what had been said to me when the police were carrying me away. From the photos two witnesses to my arrest were identified and quickly traced.

My solicitor was fairly confident that I would be acquitted, but he seemed to have some difficulty understanding the facts of my case. In early July I rang him and was told that my case would probably be up in a couple of weeks. By this time two more witnesses, who had been standing near me just before my arrest, had been found (one by HCDA and one by myself after scrutinising a picture in the ‘Guardian’ showing the crowd immediately

before I was arrested).

I met my barrister to go through the details of my case on Thursday July 12th. I was feeling good about my chances and my barrister agreed with me that we should ask for more time to prepare the case as statements had not been taken from all the witnesses. He told me to contact my solicitor the next morning so that the statements could be taken.

Then, all of a sudden, everything fell apart. When I phoned my solicitor the next day I learned he had gone on holiday. The same afternoon his secretary rang to tell me I was up in court on Monday July 16th at 10.00am and that my barrister could not make it as he had to go to a funeral.

Over the weekend HCDA took statements from my remaining two witnesses and arranged for all my witnesses to get to court. I discussed my situation with HCDA and I decided that if the stand-in barrister could not get the case adjourned I could sack him and appear unrepresented, forcing the judge to adjourn it.

I went to court determined to follow this through. However, my barrister told me that the judge could force me to defend myself. He was pretty aggressive about it and at one point told me that he wasn’t going to represent me anyway. After all this, my trial was adjourned because one of the police officers was going on holiday the next day.

On Thursday July 26 I turned up at court for trial. My barrister, the stand-in again, had another case to finish before my case could get underway. He finished in one court at 10.45am and came straight over to represent me at 11.00am.

My barrister’s cross examination of the police was pathetic. He concentrated on the structure of the TSG and a possible breakdown in police communications. This all seemed irrelevant to me as the police officers in the witness box claimed to have seen me aim blows at police officers and kick one.

At one stage I called my barrister over to me and told him to ask why the police had said in their statements that I was facing them when arrested while I was running away. He managed to trap one officer on this point, when he said he couldn’t remember if I was facing him or not. I watched the officer hesitate, and waited in vain for my barrister to point out that it wasn’t a question of memory because the contradiction was in his statement, written on March 8th shortly after I had been arrested.

When the prosecution’s case was over I could not believe that my barrister had failed to trip them up. I was sure that I would be convicted.

In the lunch break I spoke to my barrister and was gobsmacked when he said he wanted to change the defence case. One of the police officers had misinterpreted a photograph of me getting arrested and had then been contradicted by another officer. This was totally irrelevant to me as my barrister had virtually ignored their claim to have seen me attack police officers. But here he was asking me to abandon most of my evidence and that of my witnesses. By now I felt completely demoralised and so I agreed to his suggestion.

Luckily for me the support and advice I received from HCDA gave me the confidence to speak to my barrister and insist that I would be sticking to my original defence.

When I came to give evidence I actually enjoyed it. After four months of worry, and all the police lies, it was my first chance to tell people what really happened. Because the whole incident was so ingrained on my memory, I had no trouble dealing with the prosecution barrister when she cross-examined me. After my evidence two witnesses were called, the photographer who had been so crucial to my defence, and a witness who had been traced from one of his photographs.

By the end of the day I felt fairly confident. However, I could not get over my frustrations at the missed opportunities of the morning. With the evidence all heard, the summing up was to take place the next morning. That evening I made a list of all the points I wanted my barrister to make in his summing up. I’m glad I did because he mentioned all my points and, after my acquittal, bragged that he prepared his speech just five minutes before entering the court.

I was acquitted despite my barrister and thanks to HCDA, my witnesses and my own efforts. Now that it is all over this is how I feel about my case.

Firstly, I was found not guilty, but I served a four months sentence in so far as throughout that time my whole life was dominated by the prospect of a prison sentence or a heavy fine.

Secondly, the whole legal system is there to process the defendant. My barrister told me to leave all the worrying to him, all I had to do was be there. If I had done that I’d probably be in prison now. I discovered that it is essential to work on your case yourself and remember that you instruct your solicitor and barrister. Just because someone has a law degree doesn’t mean they know it all. It is very hard to avoid being sucked into the legal factory without the involvement of defence campaigns or organisations like HCDA. Apart from anything else, the actual physical presence of HCDA and my family and friends enabled me to handle the intimidatory atmosphere of the court.

Thirdly, I won. What does this mean? I won the right to carry on with my life. I have found it difficult to put the case behind me, not least because my barrister did not ask the questions I wanted asked. I wanted everyone to know, not only that there was ‘reasonable doubt’ as to my guilt, but that two police officers sat down and made up a pack of lies against me. I very much regret not defending myself, as HCDA suggested to me on a few occasions. I would love to have had one of those bastards in the witness box, not knowing what to say, and squirming in the knowledge that the whole court knew he was lying. This is the hardest thing for me to think about. I ‘got off’, but I didn’t do anything. The police ‘got away with it’, even if they didn’t convict me. They didn’t need to. They scared me and messed up my life for a bit, a conviction would only have been the icing on the cake.

Finally, the ‘authorities’ used my case, and others like it, to pretend that a load of hooligans went down to the Town Hall that night and attacked the police. the only hooligans I saw were wearing blue uniforms, and anyone who fought back has my respect.

PERSONAL ACCOUNTS

In this section of the report, we have recorded four personal accounts by people who were on the demonstration. The views expressed in these accounts do not represent the views of HCDA.

“Not like a riot”

I got the bus with my partner from Stamford Hill to Hackney Town Hall, arriving there at 5.30pm. There was already quite a large crowd. The Town Hall windows and doors were boarded up and three lines of police were standing on the steps by the front entrance. Between the entrance and the police there was a small group of protesters and public speakers.

With my partner, I went to the front of the crowd, where people were chanting anti-Thatcher and anti-poll tax slogans.

After a short while the crowd became more compact and swayed with the force of people. Some people started throwing things which caused the crowd to move away. There were several surges with people being pushed from the back into the line of police. At one point we were pushed right to the front and we both fell over. I was frightened and struggled to get back on my feet and move back into the crowd. I saw my partner fall over in front of me, and while he was trying to stand up two policemen grabbed him and, although he hadn’t done anything wrong, carried him away.

I panicked. I thought 1 must try and see where they were taking my partner. I saw another woman running to stay with her arrested partner, the police considered this to be an attack and she was hit very hard by two officers. Other policemen were grabbing anybody in their way and with much force throwing them aside. Frightened, I went back to the entrance of the Town Hall.

At about 7.45pm a young man got on the Town Hall balcony above the entrance. He waved a banner and the crowd cheered him.

People started moving to the right hand side entrance of the Town Hall. I saw the TV cameras interviewing the Liberal Democrats’ leader, Paddy Ashdown, and I though this was why interest was moving to that part of the building. People were throwing things at the lights on the porch and shouting, Some people were trying to gain access to the building.

Suddenly the police get outrageously aggressive. They started forcing people down the side street [Reading Lane] towards the square saying “Right everyone, time to go home.” I went to the protest with the intention of making a stand, a peaceful protest – I did not want to go home. I tried to stand still, but I saw other people being hit and arrested when they did not retreat. I began moving into the square.

Because I am short, I was especially aware of other women about my height, 5′ 4″, being beaten up if they tried to stand still, or make any objection to the police behaviour. I got thrown out of the way by the police on one occasion and, very frightened, ran to get away from the trouble.

At one point the police charged at us very aggressively forcing us back into the square. By this time the crowd had blocked the main road, stopping buses and cars. A police Car Came up the road and was stopped by the crowd, an ambulance was then allowed through.

I stayed in the square and watched the police make various charges towards the people in the road. Eventually I saw the police make a charge straight into the middle of the crowd splitting it into two groups. At the same time a line of police came from the Town Hall and forced everyone from the square to join a section of the crowd in Mare Street. We were then moved down the street in the direction of the Narroway. I stayed near the police line because I felt I was being denied my right to make a peaceful protest, but anyone who didn’t move down Mare Street was beaten or arrested.

As we were being forced down Mare Street, some young people ran to the shopping centre and started breaking windows and setting fire to litter bins. It was not like a riot, with looting, it all seemed hopeless and unconnected with the protest against the poll tax.

At this point I gave up and walked to the end of Mare Street. Only a few people were left in this area, some were sitting on the church wall shouting at people to stay and protest against the poll tax, other people were saying that mounted police had arrived. I walked home to Stamford Hill.

“Two demonstrations”

As chairperson of the Hackney Against the Poll Tax Federation, I was one of the organisers of the anti-poll tax demonstration. I arrived at the Town Hall at about 6 o’clock and was shocked to find the lower windows, and those of the housing office in Reading Lane, boarded up. On the steps directly in front of the main entrance a scaffolding barrier had been erected making a passage to the main door. This cordoned off section was occupied by a squad of uniformed police. A small crowd had gathered on the pavement just across the service road in front of the Town Hall.

I found the HAPTF secretary only to hear the bad news that the PA system we were expecting to be brought by the Joint Shop Stewards Committee had not turned up. I was also told that a security firm was patrolling inside the Town Hall with dogs. Only forty people were going to be allowed into the public gallery of the Council Chamber through a side entrance.

With access to the building severely limited and without a PA to address the rally, we were faced with a massive problem. How could we co-ordinate the protest? I helped set up a table on the path opposite the Town Hall, by which time the crowd was rapidly growing. I particularly noticed one man who was wearing an expensive suede jacket and casual clothes, was listening to a personal stereo, and was clearly out of his head on something. He kept demanding the placards I was laying out on the table. He finally grabbed two and walked off. The next time I saw him he was at the front of a crowd up against the police pushing the placards into the faces of the nearest two police officers.

A stand-in megaphone arrived while the HAPTF secretary was being interviewed by a TV team. When he finished we quickly discussed what to do about the rally, planned to begin at 6.30pm. Of most concern to us was the arrival of a large group of SWP supporters, with placards and megaphone, clearly planning their own actions. There was a lot of confusion at this stage. People were milling around in a strange atmosphere of expectancy, heightened by the boarded up building in front of us and the presence of TV and radio crews.

By the time we made our way to the Town Hall Steps to begin the rally, the SWP had moved like a phalanx directly in front of the police and started a loud and insistent chant. The steps had filled up and the crowd was rapidly swelling. I started to address the crowd over the megaphone, speaking about the Council meeting going on inside the building. It was clear that I was not making any impression above the volume of noise. By now it was getting dark and the TV crews were positioning arc lights at the top of the steps. I handed the megaphone over to someone with a louder voice and went down into the crowd. It was almost impossible to hear what he was saying.

Two or three more people tried to address the crowd over the megaphone before we gave up. The noise level was impenetrable, the size of the crowd much larger than we had expected. A mention on the early evening news had attracted more people than our leaflets. We had no hope of influencing the situation with our slender resources. My previous anxiety to control what was happening gave way to exhausted detachment. From the steps I could see people hanging out of bus windows as they drove along Mare Street. In front of the steps there was a dense crowd of mainly young people, in a semi-circle around the square there were families, older people and onlookers. I went down to join them.

Scuffles broke out. I couldn’t see why, but I could see that the TV lights trained on people had the effect of raising the temperature. Finding themselves literally in the limelight increased the excitement in that part of the crowd and among the police. And that, for the most part, was all that TV viewers saw. They didn’t see the large numbers of people standing back around the square in the shadows. But these people were just as angry with what the council was doing behind closed doors and boarded up windows. You could tell their feelings by the way they clapped and cheered when a young man climbed up on the balcony overlooking the square with a large “Pay no Poll Tax” banner. Occasionally the crowd was split up by a police charge.

To my mind there were two demonstrations. One was active, the section that surged round to the side entrance in Reading Lane when it was discovered that Paddy Ashdown was addressing a meeting, and then stopped the traffic in Mare Street. And the other was passively watching, moving out of the way when trouble came their way.

Later that night the active demonstration was in Mare Street, the steps were almost deserted. I showed a friend the way to the nearest toilets in the Florfield pub. Returning ten minutes later there was a police cordon across Reading Lane. A police officer informed us that we couldn’t get through to the Town Hall, it was now a “sterile area”. We then decided to make our way home.

“Love to have a go”

I arrived at the Town Mall at 6.10pm on the night of March 8th. I recognised many faces in the crowd of about 400. I had walked to the demonstration through the back streets, where I had seen a large number of buses and vans with police sitting in them.

I wasn’t surprised to see the Town Hall boarded up as I had been told about it earlier in the day. I had also been told about groups of young people hanging around the Town Hall asking ‘what time’s the riot?’

I wanted to do something, so I helped to give out the HCDA bust-Cards. Initially this involved walking in and out of the crowd, and I took the opportunity to chat to people I knew. As the crowd continued to grow it became impossible to continue walking about, so I stood in one spot on Wilton Way and gave out the bust-cards to people as they arrived. The majority of people were only too willing to take the cards. Some older people on the fringes of the demonstration said they didn’t need them, as did some casually dressed young men who looked like plain clothed police.

As the crowd continued to grow, a fairly large number of people who I would describe as squatters began to arrive. Virtually all of these people collected bust cards and then moved into the area directly in front of the police at the bottom of the Town Hall steps. This area was filled almost exclusively with squatters. Members of the Socialist Workers Party were lined up behind the squatters chanting slogans.

The first arrests came after many things had been thrown at the police. After I had finished giving out bust cards I joined the protest on the Town Hall steps. From there I watched members of the crowd throw bottles, beer cans and the occasional placard at the police. I saw one smoke bomb thrown. Many of the missiles missed the police and hit other demonstrators. I cannot recall seeing a single police officer getting hurt and being taken away as a result of the crowd’s actions. At the front, a number of people were spitting on police officers and some were making gestures of defiance, such as ‘V’ signs. Officers from the left hand side of the Town Hall began to arrest a number of people and as they were pulled away quite a large number of people tried to rescue them.

A black lad managed to scramble on to the balcony and hoisted above his head a ‘Pay No Poll Tax’ banner. He was greeted with tremendous applause and cheering by the crowd. The lad was clearly enjoying himself, but after a few minutes the crowd lost interest in him and you could see the anxiety on his face. He was obviously worried about the risk of getting arrested when he got down.

At this point a number of people announced that Paddy Ashdown was speaking at a Liberal Democrat’s rally at the side entrance to the Town Hall, many people started moving in that direction. The lad on the balcony saw his opportunity to climb down, and was assisted by people on the steps near him.

As we moved towards the Paddy Ashdown meeting, police got out of their vans and buses. A number of people managed to get into the hall and were quite forcibly removed. Hand to hand fighting broke out as the police struggled to retain control. As the crowd moved away from the side of the Town Hall a number of people decided to stop the traffic on Mare Street. People were extremely happy and shouting loudly. Some people sat in the road, but most people didn’t bother.

I walked along to the area close to the Hackney Empire and saw a car being escorted by the police. Someone shouted that it was Glenys Kinnock and there was a lot of booing. A number of people were kicking the car and were brutally attacked by police officers who quickly ran to the area. I saw one demonstrator viciously thumped and knocked over before being arrested. One young black lad looked to be badly hurt as he was pulled into a police van.

A young white lad had been knocked off his motorbike and an ambulance turned up to take him away. As the ambulance drove through the crowd there was a huge cheer and applause. The crew were smiling and waving back. Earlier, a St John’s ambulance had been refused the right to travel through because, in the words of some demonstrators, ‘they had scabbed on ambulance workers’.

At about 8.45pm the police must have decided to try and clear everyone from the area and began making charges to the left and right.

Thinking back on the demonstration I am critical of many of the organisations involved. It was the Poll Tax Federation who organised the demonstration, but they took no account of just how angry people were. Surely they must have known that the presence of so many police around our boarded up Town Hall was bound to be seen as provocative. The union leaders involved in organising the demonstration were incompetent for not providing a PA system so that a rally could take place. The two main political parties behind the demonstration, Militant and the Socialist Workers Party, earned no respect from me that night. Militant supporters, of which there were very few present, stayed well away from the main body of the demonstration. The Socialist Workers Party, while chanting extremely loudly and encouraging others to have a go, did little more than this.

In conclusion, it has to be said that there were a few people who turned up with the intention of attacking the police. The police were able to launch a number of attacks against angry but peaceful demonstrators, who were not on the whole prepared to defend themselves. It seemed to me that by the end Of the demonstration many people would have loved to have a go and attack the police, and only did not do so because they were not organised.

Sacked for an extended tea break

March 8th was International Women’s Day at the Hackney Empire. As an employee of the theatre I went to work as usual. On my way into the building I couldn’t help but notice the crowd that was gathering in the Town Hall square to protest against the poll tax.

I was working in the upper circle of the theatre, the door of which directly faces the Town Hall. Whilst tearing tickets I watched more and more people come to voice their disapproval of this unjust tax. I could hear their anger as they saw that the Town Hall was boarded up, and that the majority of them would not be allowed into the meeting. Somehow, bypassing the barricade of police who were guarding the Town Hall, a young black guy managed to climb up onto the balcony overlooking the square.

The crowd roared, some shouted to him to break in and disrupt the meeting. After this I went upstairs into the Empire. After about half an hour of the show I decided to take my tea break and join the demonstration.

Outside the mood had changed. People were getting angrier, and frustrated. Anti police and Thatcher songs were being chanted with the crowd throwing things and spitting at the police.

Suddenly, the crowd surged forward and the police, who had previously been calm, retaliated. I was standing in the middle of the crowd. I was being pushed from the rear, and the people in front of me were trying to escape the police truncheons, for a moment I felt as if I would be crushed to death. But the whole crowd seemed to disperse backwards onto Mare Street.

Then everybody seemed to go mad. It was war, with the police charging into the crowd, not caring who they hit and certainly not caring who they arrested. A group of about 150 people sat down in Mare Street trying to stop the traffic, but a police charge dispersed them.

I saw a friend of mine who told me she had been tending to an injured journalist. “I was standing there cleaning his eye” she said, “and all of a sudden this plain clothes policeman arrests him.”

I don’t know how long it was before the police started to push the crowd towards the Narroway, surrounding the Empire and denying anyone entry, but when I tried to get back to work I was unable to. I told them I worked there, but they said I would have to walk the long way round. It was approaching the interval and I knew I should be back at the theatre.

As I walked round, I ventured up the Narroway to see what was going on. People were smashing up the shops, especially Marks and Spencers and MacDonald’s, but I didn’t see any looting.

Finally, after about three quarters of an hour, I got back into the Empire and resumed my duties; my tea break should have been for fifteen minutes.

The following day I was sacked from my job. The reason given was that I had left my post to join the demonstration. Even though I explained the situation, that I could not get back into the building, the Hackney Empire’s management felt that my dismissal was warranted. I have taken my case to the Transport and General Workers Union, and they are currently dealing with it.

WHAT THE PAPERS SAID

“POLL TAX MOB LOOTS SHOPS” read the front page headline in the ‘Sun’ of Friday March 9th; “MOB RULE” blurted ‘Today’: “LOOTERS ON RAMPAGE” screamed the ‘Daily Mirror’. A photograph of a man throwing a missile through MacDonald’s window featured in four national newspapers.

“PM BLAMES MILITANCY ON LABOUR” said the ‘Guardian’, likewise the ‘Times’ “THATCHER HITS AT MILITANT OVER POLL TAX”.

These were the two themes which dominated the national press coverage of the Hackney anti-poll tax demonstration. The “gutter press” focused on the looting that took place, and the “quality press” concentrated on Militant’s involvement in the campaign against the poll tax, but still found space to highlight the looting. The looting theme was returned to on Saturday 11th with many papers visiting the Narroway to speak to shopkeepers and assess the damage to the 43 shops which had their windows smashed. The most notable exception to the national press’s coverage was the ‘Independent’ whose March 9th frontpage headline read “POLICE BATON-CHARGE POLL TAX PROTESTERS”. And Hackney’s local, the ‘Hackney Gazette’, gave a more balanced report on the events of the evening under the satirical headline “A TAX OF DERISION: ATTACKS OF HATE….”.

In general the press did what they do best – sensationalise events in order to sell their newspapers. The violence was attributed to Socialist Workers’ Party, Militant and anarchist agitators (the ‘Times’ even went to great lengths to explain how anarchists have co-ordinated anti-poll tax protests as a disciplined force), there was, however, no mention of what it’s like to live in Hackney.

Margaret Thatcher, never one to miss an opportunity to politick at Labour’s expense, was given much space to attack Militant and the 30 Labour MPs who had stated their intention not to pay the poll tax. These MPs, she intimated, were directly responsible for the violence, a conclusion she reached while 400 miles from Hackney in Glasgow. Paddy Ashdown, a veteran of the British Army’s ongoing campaign against Irish nationalists, was there on the night, so he was more than qualified to compare the Hackney scenes to those he had witnessed in the six counties. Did he, we wonder, secretly feel the need for the same solutions? Hackney’s own chief of police, Chief Superintendent Niall Mulvihill, came over as the personification of reason itself, as he explained how local people had the right to demonstrate and had done so in a peaceful manner only to be upstaged by a small hard core of agitators.

As might have been expected by the people who attended the demonstration, the media’s coverage of events bore little resemblance to what took place that night. Militant hardly figured at all in the demonstration, and there was actually very little looting. Although protesters did take out their frustrations on business premises, the damage only occurred after the police forcibly ended the demonstration by pushing people in the direction of Hackney’s shopping centre.

CONCLUSION

This report has tried to put the events in Hackney on March 8th in the broader context of political protest against the poll tax. ‘Criminalisation’ has been a cornerstone of the government’s policing policy throughout the 1980’s, but nowhere is the criminalisation of legitimate protest seen more clearly than in demonstrations against the poll tax. In the ‘Daily Express’ of March 9th, Thatcher said of the Hackney demonstration “It is precisely the type of violence we have seen before at Grunwick, in the coal strike and at Wapping, and it is the negation of democracy.” On Saturday March 31st, the eve of the introduction of the poll tax in England and Wales, a national demonstration marched from Kennington Park to Trafalgar Square. Again there were running battles between police and demonstrators with widespread damage caused to London’s West End. The events of that day, the massive police follow-up operation to make more arrests, and the severity of the courts in sentencing, confirms that the government, police and courts are sparing no expense to criminalise the protest against the poll tax.

The criminalisation of protest is a political strategy by which the government, police, courts and media, combine to portray demonstrators as criminals engaged in illegal activity. For the strategy to work there has to be a high number of arrests followed by convictions in the courts. The only means by which the organisers of demonstrations can challenge criminalisation is by setting up defendants’ campaigns, and by winning the court cases, in order to demonstrate that the policing of protest is a political not a legal concern.

Labour controlled Hackney Council has always prided itself in running local services with an open door policy. On the evening of March 8th, when important decisions were to be made concerning the future of Hackney, the Town Hall was boarded up, private security guards with dogs patrolled the building, and only a few members of the public were allowed into what should have been a public meeting. It was inevitable that such actions were going to provoke hostility amongst demonstrating residents. It is evident that in the early part of the demonstration, until 8.00pm, protesters were attempting to gain access to the Town Hall. In order to do so they had to overrun police lines, and police officers were used as a buffer against an angry crowd.

Following the spate of demonstrations against the poll tax across the country in the days preceding the Hackney demonstration, the Hackney Against the Poll Tax Federation should have been aware of the likelihood of a disturbance. The Town Hall unions, who had become aware of the security arrangements earlier in the day (including the mounting police presence), must have known that the council had set a course for confrontation. Yet no attempts were made to organise stewards for the demonstration. much more importantly, the absence of a public address system meant that the planned rally could not go ahead. 5,000 people attended a demonstration without a focus and without speeches to listen to; what else were people going to do other than hurl abuse at the police officers between them and the subject of their anger?