A PDF version of this pamphlet (and others by HCDA) is available here.

ON THE BORDER OF A

POLICE STATE

A campaigning pamphlet on three government reports on the police and a campaigning strategy for challenging the emergence of a police state.

HACKNEY COMMUNITY DEFENCE ASSOCIATION

HACKNEY TRADE UNION SUPPORT UNIT

Copyright. Hackney Community Defence Association

and Hackney Trade Union Support Unit

September 1993.

HACKNEY COMMUNITY DEFENCE ASSOCIATION

Hackney Community Defence Association (HCDA) campaigns against police crime and oppression. HCDA provides support for the victims of police crime,. It has prepared criminal defence cases and is presently supporting more than 30 civil actions against the police. HCDA publicly exposed drug dealing by Stoke Newington police officers.

HACKNEY TRADE UNION SUPPORT UNIT

Hackney Trade Union Support Unit (TUSU) campaigns to rebuild militant trade unionism. TUSU provides advice on employment rights and trade unions, supports strikers, runs recruitment campaigns and produces a quarterly union bulletin in English and Turkish It has developed close links with the local Turkish and Kurdish community.

COLIN ROACH CENTRE

HCDA and TUSU joined together to set up the Colin Roach Centre. Named after a young black man killed in the foyer of Stoke Newington police station, the centre is a politically independent resource for community groups and trade unionists.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

THREE REPORTS

White Paper on Police Reform

Inquiry into Police Responsibilities and Rewards

Royal Commission on Criminal Justice

Implications

FIGHTING BACK

Community Defence Campaigns

A Role for Trade Unions

Campaigning for Reform of Police Powers

LURCHING FROM CRISIS TO CRISIS

Chronology

INTRODUCTION

In 1980 Lord Denning dismissed an action by the Birmingham Six against the West Midlands Police for assault. He said if the men were to win “This is such an appalling vista that every sensible person in the land would say: It cannot be right that these actions go any further.”

To some degree he was right: the legal establishment’s belated admission that innocent people had been fitted up threw the criminal justice system into crisis. The Guildford Four were released from prison in October 1989 and the Birmingham Six in March 1991. The release of the Birmingham Six was accompanied by the setting up of the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice, with a brief to make recommendations on how to avoid future miscarriages of justice.

For two years, up until the publication of the Commission’s report on 6 July 1993, the police have been widely criticised (see Chronology, below). The political agenda was dominated by the crisis in the criminal justice system and the need to restore police credibility.

The police have been attacked from all sides:

- failure to cope with rising crime figures

- ineffective use of resources

- outdated management practices

- racial, sexual and sex orientation discrimination

- internal police complaints investigations

- obsessive secrecy

- lack of political accountability

- abuses of power as exposed by community defence campaigns.

In the space of a week, the political agenda changed. On 28 June the government published its White Paper on Police Reform. On 30 June the report of the Inquiry into Police Responsibilities and Rewards (the Sheehy report) was published and the Royal Commission reported on 6 July.

These three documents have radically shifted the debate away from the crisis facing the police and criminal justice system to the problems the police face in fighting crime, and the overbearing expense of the criminal justice system. They collectively conclude with recommendations to strengthen the corporate powers of the police.

This pamphlet is about the threat of a police state in Britain and how it can be challenged. For black communities, living in inner city areas, a police state already exists. Powerless people living in criminalised communities are targeted by the police for attack. Many of the celebrated miscarriage of justice victims are Irish. Although unconnected with the IRA, these people suffered years in jail as a result of Britain’s war with Ireland. The government’s refusal to contemplate their innocence for so long indicates the lengths to which the state is willing to go to protect its interests. Other people – trade unionists, political activists, squatters, travellers and football fans – also have first hand experience of police oppression.

For most people attacked by the police, injustice represents a disturbance to their everyday lives. They are assaulted or fitted up and life goes on – unemployment, money worries, bad housing, poor schooling, or whatever. The victims of police crime suffer an isolating experience. They may have to go to court and plead innocent to a fabricated charge or make a complaint against a police officer or sue the police. The victim just wants to put the unhappy episode behind them and get on with their lives. In these circumstances, campaigning has been left to single issue defence campaigns and lawyers, who have to deal with injustice all the time.

Police crime is not even recognised. It is called malpractice, wrongdoing, injustice, racism and anything else but crime. The police attempt to address the problem of police crime internally, by a complaints procedure and not by criminal law. The most regular crimes committed by police officers are conspiracy to pervert the course of justice, perjury and assault. To date not a single police officer connected with the celebrated miscarriage of justice cases has been convicted of a criminal offence. There has been a reluctance to bring charges in the first instance. When three ex-Surrey detectives were eventually tried in court, for fabricating evidence against the Guildford Four, the prosecution prepared a feeble case and the men walked free. It is standard practice for the authorities to cover up police crimes of this nature. When police officers engage in a bit of straightforward criminal endeavour, like Stoke Newington officers’ drug dealing, the police complaints procedure falls apart and spends years examining itself behind closed doors.

The issue of policing is far too important to be left to lawyers, and it is too deep rooted to be challenged by single issue campaigns. Police injustice affects the whole population. Not everybody in a community has to be assaulted or fitted up to live in fear of the police. It is enough that people know it happens, and that little can be done about it. The majority of the population does not suffer directly from the powers of the police, but we are all influenced by their political role. The police define crime, and report to the government on what needs to be done. The police are the source of many stories for the local press, radio and TV. Where criminal offenses have not been committed, the police question people’s behaviour and assume the role of moral guardians. Nobody has been charged in connection with the recent so called “home alone” children, but the police informed the whole nation about their “irresponsible” mothers.

There are two policing issues which need addressing. Firstly, the prevalence of police crime and the lack of adequate formal means of redress. And secondly, the increasing power of the police as a corporate institution and their intervention in the political arena.

The last time police powers were on the political agenda was in the mid-eighties, during the miners strike and Wapping dispute, the Broadwater Farm, Brixton and other disturbances and when the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) and the 1986 Public Order Act (POA) became law. At that time Municipal Socialism was at the height of its influence and Labour run local authorities, including the Greater London Council, played an important part co-ordinating challenges to the police’s power. Today, municipal socialism is dead, and there doesn’t appear to be anybody to take up the fight.

This pamphlet aims to do three things. Firstly, it outlines the key proposals contained in the White Paper, Sheehy and Royal Commission reports as they effect the police. Secondly, it attempts to provoke a public debate on the police. And thirdly, as part of that debate, it proposes a twofold strategy for fighting back against the police in our communities and trade unions on both an individual basis, supporting the victims of police crime, and on a political level – fighting the emergence of a police state.

Note: The British government also has responsibility for policing in the six counties of Ireland. This pamphlet does not discuss policing in Ireland, we accept that Irish people have the right to decide for themselves how to challenge police powers in their own country.

THREE REPORTS

The government is planning to replace the 1964 Police Act with a new bill later this year. The White Paper on Police Reform outlines the government’s proposals for change. It examines the roles of the Home Secretary, Police Authorities and Chief Constables and recommends changes which will transfer powers presently held by the Home Secretary and police authorities to Chief Constables.

The White Paper is supported by the Sheehy report into police responsibilities and rewards. Sheehy’s findings are essentially concerned with the internal management structure of the police and recommends bringing “sound business practices” to the police. The government intended incorporating Sheehy’s recommendations into the new Police Bill, but is now negotiating with police representatives as a result of their opposition.

Whereas these two reports deal with the administration and management structure of the police, the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice deals with matters of law concerning the investigation of crime and the criminal justice system. It is intended to form the basis of criminal justice legislation in the next parliamentary session. We are only concerned with the Royal Commission here as far as it concerns the police.

WHITE PAPER ON POLICE REFORM

Police authorities do not have much power. London doesn’t even have one. The Metropolitan Police Service is answerable only to the Home Secretary. The 42 police authorities are sandwiched between a Home Secretary with the power of veto and Chief Constables who are in a position to ignore them. However, they include a majority of locally elected councillors, alongside appointed magistrates, and bring the only element of democracy to policing.

The White Paper purports to be concerned with police performance and accountability. In summary its main recommendations are as follows.

Chief Constables’ new powers

- Responsibility for manpower levels to be transferred from Home Secretary.

- Responsibility for civilian staff to be transferred from police authorities.

- Responsibility for vehicles, uniforms and equipment to be transferred from police authorities.

- Responsibility for maintenance and management of buildings to be transferred from police authorities; proposed.

These recommendations add to Chief Constables considerable powers. They already have total control over police operations. According to the Home Office, 80% of expenditure on the police is spent on pay (Royal Commission Report; Chapter 1, para 19). Therefore, by giving Chief Constables responsibility for staffing levels, they will have full control over 80% of their budgets. And, vehicles, uniforms, equipment and buildings will account for a large proportion of the remaining 20%.

Police authorities

- To consist of 16 people. Eight members to be elected councillors, three to be magistrates and five to be appointed by the Home Secretary.

- Chairperson to be appointed by Home Secretary and salaried.

- Responsibility for ensuring Chief Constables’ annual budget and performance reports meet Home Office and local requirements.

- Responsibility for setting annual budgets in consultation with Chief Constables, which is liable for capping.

- Responsibility for police community consultation. Responsibility for monitoring finances and performance.

- Responsibility for publishing performance results for comparison with other forces. Can ask Chief Constables to retire with the Home Secretary’s approval.

The major change recommended here is for the government to assume greater control over police authorities through the Home Secretary’s appointment of five members and a salaried chairperson.

Home Secretary’s role

- Responsibility for key police authority appointments (above).

- Responsibility for policing London through appointment of an advisory committee.

- If police authorities fail to discharge their statutory duties, the power “to put matters right”, including the power to overrule budgetary decisions.

- Responsibility for cash limited funding. It is undecided whether Home Office to provide 100% funding.

- Power to determine boundaries of police force areas.

Despite much public pressure, the government has decided against setting up a Metropolitan Police Authority. The government has also reserved the power to reduce the number of police forces through amalgamation.

Police duties

- An end to standard eight hour working shifts.

- Devolving police responsibilities from central command to local control.

Introduction of a two tier disciplinary procedure which distinguishes between work related misdemeanors and matters of public concern. - Proper attention to be given to police training at all levels.

- Increased recruitment of special constables.

On the specific details of police management, the White Paper refers to the Sheehy inquiry.

INQUIRY INTO POLICE RESPONSIBILITIES AND REWARDS

The report of the Inquiry into Police Responsibilities and Rewards – the Sheehy report – is a thorough analysis of police management. It comes as no surprise that the police have denounced it so vehemently. The report systematically takes the police apart, and recommends putting it back together with a programme of inducements and penalties which will divide senior from junior ranks and set officer against officer. The Sheehy report contains 272 recommendations, too many to go into much detail here. We simply attempt to give a brief summary.

Rank structure

The inquiry found that the police are top heavy and recommends the middle ranks of Chief Inspector, Chief Superintendent and senior rank of Deputy Chief Constable are abolished. 5,000 posts to go with 3,000 more constables recruited. Six ranks to remain – Constable; Sergeant; Inspector; Superintendent; Assistant Chief Constable; Chief Constable.

Pay levels

The inquiry found that the present pay scales guarantee pay rises regardless of responsibilities and performance. It recommends ending index linked annual pay awards. Pay to be related to non-manual private sector rates. Up to Assistant Chief Constable rank, pay scales to be determined by a complicated 12 point matrix based on responsibilities, working conditions, experiences, skills and performance. Pay for Assistant Chief Constables and above to be determined primarily according to performance.

Pay differentials

If Sheehy’s recommendations are introduced, starting salaries for recruits will be lower than at present. Constables and Sergeants salaries will be reduced slightly. Inspectors salaries will increase by about 5%. Superintendents will be entitled to a 10% performance bonus which, if achieved, will increase their earnings by about 8%. Assistant Chief Constables and Chief Constables salaries will carry 30% bonuses.

The rationale behind the increased pay for senior officers is that their responsibilities will be increased as a result of legislation proposed in the White Paper (including greater management responsibilities over junior ranks).

Job security

The inquiry found that police “jobs for life” are a privilige not enjoyed by other workers and recommends the introduction of fixed term contracts of 10 years on recruitment and then every five years. Contracts can be ended for misconduct, poor performance or on structural grounds (ie in the interests of the force).

Pensions

Recommends increasing retirement age from 55 to 60, an end to fast accrual of pensions after 20 years service and restrictions to grounds for medical retirement.

Pay related conditions

The report recommends an end to open ended sick leave, housing, overtime payments and other allowances.

ROYAL COMMISSION ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE

The debate on miscarriages of justice has focussed on the belief that something went wrong. The fact that police officers committed criminal offenses to secure wrongful convictions has been conveniently ignored. The Royal Commission did not consider the problem of police crime and its detection.

Even the wrongful convictions of innocent people was too much for the Commission. It preferred to look at the problems the police have in convicting the guilty. In the main it recommends the strengthening of the police and the prosecution by entrenching and safeguarding their powers at the expense of defendants rights.

Independent supervision of police

The Commission does not recommend any form of independent supervision of the police at any level or stage. In police stations it considered, and rejected, the need for an independent, non-police, custody officer to be responsible for suspects welfare and charging. Instead the Commission recommends the strengthening of the existing Custody Officer position, and the appointment of an officer above the rank of sergeant in busy stations.

Although the Commission recommends the setting up of an independent miscarriage of justices review authority, with powers to refer cases to the Court of Appeal, it does not provide it with investigative powers. It would supervise police investigations and ask for an outside force to be called in. [The same limited powers are already available to the Police Complaints Authority (PCA).]

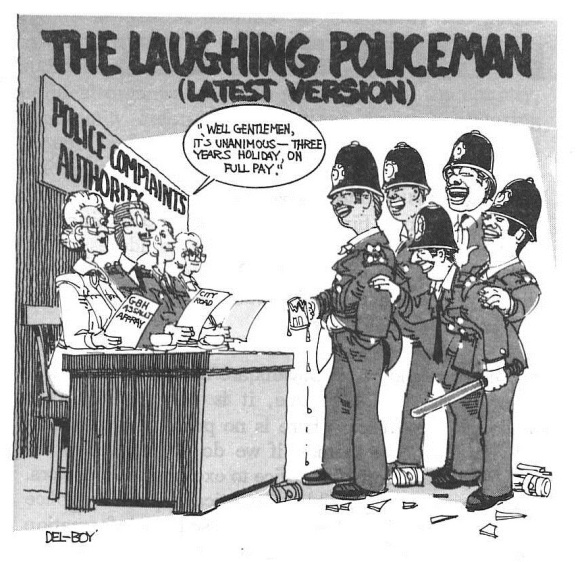

Police complaints

There are no recommendations for independent investigations of police complaints, nor for changes to the PCA. There are six recommendations:

- An end to the double jeopardy rule which means police officers cannot be the subject of disciplinary proceedings if acquitted of a criminal charge regarding the same incident.

- The standard of proof required to find a complaint to be reduced from ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ to ‘on the balance of probabilities’.

- Where civil actions have been brought, disciplinary action to be considered. Dismissed officers to seek damages for wrongful dismissal instead of appealing to the Home Secretary.

- Where courts criticise officers, a formal mechanism to be established to inform chief officers. Compilation of national statistics on police disciplinary affairs.

In addition, the Commission recommends setting up a “helpline” for officers to speak to senior officers about malpractice.

Police complaints are rarely proved because of imbalances in the police’s favour. Widespread public criticism of the police, and the succession of high profile miscarriage of justice cases through the Court of Appeal, forced the Appeal judges to respond to public pressure. In January 1991, Lord Chief Justice Lane ruled in the case of John Edwards, that if a defendant makes an allegation against a police officer which is similar in time, place and nature to a previous case, where the officer has been disbelieved by a jury, then the defendant has the right to cross examine the officer in court about that previous case.

This was a landmark judgement which has allowed juries to be informed, to a limited degree, about officers’ work records, and then make up their own minds. The Royal Commission recommends that legislation is introduced to withdraw this right, and that the defence should only be entitled to cross examine about disciplinary actions which have been proved and are similar to the defendant’s allegation.

Confessions

A common way in which the police fit people up is by “verballing” – the fabrication of conversations they allege to have had with the suspect at any time in custody. The Commission does not recommend excluding this evidence, it proposes that after consultation with a solicitor, the suspect is given the opportunity to comment on the alleged comments at the beginning of a taped interview.

There has been a great deal of publicity about the police’s pressurising vulnerable people into making confessions which are often unsupported by other evidence. The Commission does not recommend an end to the use of uncorroborated confessions, it proposes that judges issue juries with warnings in such cases.

Strengthening the police

Other principal ways in which the Royal Commission’s recommendations will strengthen the police are:

- By allowing investigating officers to continue interviewing suspects after they have been charged. At present, as soon as there is enough evidence to charge a suspect with a criminal offence interviews must cease.

- By providing the police with the power to set bail conditions. At present the police can release defendants on unconditional bail; only a magistrate can set conditions. The majority of suspects are released from police stations on unconditional bail, if the police are given the power to apply conditions they will be in a position to punish suspects before trial.

- By requiring the defence to disclose the substance of its case to the prosecution. This will give police officers the opportunity to concentrate their investigations on disproving the defence case instead of proving the defendant’s guilt. This recommendation goes against the universal principle in criminal law that a person is innocent until proved guilty.

- By denying people the right to elect jury trial in a significant number of cases. This will condemn defendants to trial in what were called Police Courts and are still known as such in working class communities.

Safeguards for suspects

The Commission recommends video recordings in custody areas and proper adherence to the Police and Criminal Evidence Act Code of Conduct.

IMPLICATIONS

Members of the establishment are not much interested in the administration of justice, an expensive and messy business which always goes wrong, so they cobbled together a scrappy report which concentrates on cost cutting. However, 80% of the £6.8 billion spent on the criminal justice system in 1991 was spent on the police and forensic science service. The Commission states that police resources are outside its remit and refers to the Sheehy report on this issue (Chapter 1; para 19). The Commission only concerns itself with cutting costs at the expense of defendants.

The Royal Commission’s report is about as well thought out as the poll tax, with the same principles in mind. Like the welfare state, the British economy cannot support justice, so it is looking for ways to dismantle it.

Management models, man management and the legitimate use of physical force are much more appealing to the establishment’s imagination. The only thorough report presented in the summer of ’93 is Sheehy’s on the restructuring of police management, and cutting policing costs. Sheehy really got his teeth into the police, and how they have responded. 23,000 off-duty policemen from all round the country attended an evening rally in Wembley. Britain’s senior policeman, Paul Condon, stated the report “undermines the office of constable”. In response to police pressure, the Home Secretary, Michael Howard, has had to hastily convene meetings with police representatives. For the government there is method in this madness. The powers of the police have increased to such a degree that, although they are servants of the state, their autonomy is a threat to the state. The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) is an unelected and unaccountable organisation of police employees of the rank of Assistant Chief Constable and above. It has assumed the role of a national police force and even represents Britain on a formal level in the European Commission. The way in which ACPO mobilised police squads across the country during the 1984-5 miners strike must have caused quiet concern in government circles.

We are living in a time when society is rapidly changing. The past 30 years have seen social and economic experiments in public ownership followed by privatisation, economic crises, unemployment, poverty, collapsing services, etc. External changes are being forced on Britain with a changing relationship with the United States, European Union and challenges to the sovereignty of Parliament. The British nation state itself is being transformed. In this situation, strong police powers are necessary to the maintenance of order and their autonomy is a threat to the government. The government wants a strong police force, an undemocratic police force which is answerable to the government. This poses a dilemma for the government, it cannot achieve the impossible. Worse still, the government has to accept that the police have already assumed political powers and are established at the heart of the political process.

The three reports address different aspects of this problem and recommend changes which will maintain a strong, anti-community police force, with allegiances to the state. The three reports dovetail nicely with each other. What the Royal Commission does not consider, Sheehy looks at, and the White Paper provides a general overview for the government. The consequences of the three reports, if implemented, will be to separate senior police officers from the junior ranks, and formally draw them into the political decision making process.

The government’s immediate problem is the lack of control over individual police officers and their loss of credibility at a time of increasing crime. The police are unaccountable. The government does not want to take away police officers’ immense powers. It only wants to determine when, where and against who they can be used. If individual officers use excessive powers, a mechanism is needed for holding them to account – not to the law, to the police.

The government perceives the problem as a management issue, not a legal problem. They have refused to address the problem by legislative changes to the criminal justice system. This could have been done by restricting police powers, either by giving them to somebody else or allowing for independent investigation of the police. The government preferred to give the problem to Sheehy to deal with as a management issue. He recommends empowering senior officers with tighter controls over the junior ranks who have responsibility for policing the streets. The powers of individual police officers are to be controlled by giving police management responsibility for deciding whether an officer’s fixed term contract is going to be renewed or how much s/he is going to earn in which particular job. Police performance plays a central part in the Sheehy report. It is an officer’s performance, good or bad, which will determine his or her salary and retention in the job. In order to be effective, there have to be easily recognisable work performance indicators which senior officers can apply. At the heart of this system lies the proposed new police disciplinary procedure – a two tier system which distinguishes between poor work practices – lateness, untidiness, rudeness, etc. – and what the authorities call “matters of serious public concern”, what we call police crime. Thus, police crime cannot be dealt with by the criminal justice system, it has to be covered by the police disciplinary procedure. It becomes the responsibility of senior police officers to decide if a “disciplinary offence”, not a criminal offence, has been committed and what the penalty should be. For this system to work, an easier method of disciplining officers would be a great help. The Royal Commission has obliged by making six recommendations to the disciplinary procedure which will strengthen police management.

While Sheehy recommends strengthening police management within the force, the White Paper strengthens senior officers by transferring powers to Chief Constables and disempowering police authorities. The White Paper legitimises existing practices by formally transferring responsibilities to Chief Constables which they had already assumed. In this way, Chief Constable’s political powers have been formally recognised by the government.

For the government, the most important role of police authorities is not to hold the police to account, it is to liaise between the police and the community: “They [police authorities] will help to build a partnership between the police and the local community by explaining what people can do to support the police in their work. This will oblige them to involve the public in the work of the police.” (White Paper; Chapter 4, para 15; their emphasis). The government’s strategy of legitimising the position of senior police officers in the political arena is wrought with dangers. If proposals in the three reports are introduced as recommended, senior police officers will become some of the most powerful individuals in the country. They will be supported by an elitist ACPO, which if the number of forces are reduced, will become even more exclusive. Britain is on the border of becoming a police state.

There is a devious logic to the governments thinking, but the political powers of the police are such that they are fighting back against Sheehy on all fronts. Condon found the government out straight away, and stated in an interview with the Observer that Sheehy “undermines the office of constable” (Observer 25 July 1993). Condon is right, the government is attempting to use management methods to check legal powers.

The police have informed the government that they do not accept Sheehy’s report, and following a meeting with ACPO on 27 July, Howard said: “It is clear that changes will have to be made,” (Guardian 28 July 1993). Sheehy himself summed up the problem: “Police are just ordinary persons with special powers. If we give them jobs for life; there is a tendency to feel special … which can affect their attitude to the public in a negative way.” (Independent 31 July 1993).

The police are setting the agenda. Senior and junior ranks have united against a weak government which has lost direction since the departure of Margaret Thatcher. It is probable that senior officers, who have a lot to gain financially from Sheehy, believe the government does not have the will to implement the report’s recommendations and they are supporting the junior ranks in their anti-Sheehy campaign. However, negotiations are continuing, and there is a possibility that senior officers will side with the government on the issue of fixed term contracts, and junior officers will maintain some of their financial perks. Alternatively, it may be that the police believe they are able to resist all reforms, and we are not so much moving towards a police state, but have already arrived.

It remains to be seen what compromises are eventually thrashed out, but legislation is heading in the direction of the police becoming a stronger corporate institution, with many of the oppressive powers of individual officers untouched.

FIGHTING BACK

Working class communities are confronted by two related problems. Firstly, police crime, as committed by individual officers and which need to be addressed by community defence camapigns. Secondly, the increasing powers of the police, which require a political campaign to demand legal changes.

Police crime and police powers are two different issues. In order to challenge one, it is also necessary to challenge the other. There is no point in challenging individual officer’s crimes, if we do not challenge the authority that allows the police to exercise such powers. Likewise, it is not possible to politically question police powers unless that challenge is based on information collected by taking up individual cases of police crime. Campaigns around these two issues give meaning to each other.

COMMUNITY DEFENCE CAMPAIGNS

Community defence campaigns challenge police crime in a practical way and cope with people’s real needs. They represent a political defence against police repression Community defence campaigns can be set up by anyone in response to attacks by the police against members of a community. They either arise spontaneously or are set up by community groups or political organisations. In some areas of the country, community defence organisations, police monitoring groups and community law centres, have ongoing defence campaigns which strengthen their communities’ understanding of the police and their abilities to organise effectively.

There are five main elements to community defence campaigns:

- victim support

- legal support

- investigating the police

- seeking redress

- publicity.

Victim support

Many of the cases of police crime involve assaults by police officers. The victims are then fitted up with criminal charges against their assailants. The most common charges are assault, threatening behaviour, disorderly conduct and obstructing an officer in the course of their duty. All these charges can be used to legitimise a police officer’s assault on the victim.

It can be an extremely isolating and traumatic experience to be assaulted by a police officer. The very institution we are supposed to turn to for protection, is responsible for our fear. Similarly, being fitted up by the police leaves victims feeling powerless and at the mercy of a legal system which has misplaced emphasis on the honesty of police officers.

Community defence campaigns allow people to meet others with similar experiences and knowledge of police crime. They can be referred to counsellors experienced in policing issues. By discussing factual aspects of their cases, victims can overcome their powerlessness and are able to deal more effectively with their situation. This is particularly the case if the victim has to defend themself against criminal charges in court. The presence of a number of supporters gives confidence in the alien environment of a court room, which is the police officer’s second home.

Legal support

A good, specialist solicitor is the first priority for any victim of police crime. Whether a person has to defend themselves against a criminal charge, make a complaint or sue for damages, a good solicitor with experience of police crime is essential. A good solicitor should then instruct a similarly specialist barrister.

Community defence campaigns can advise victims on the best solicitors to use, and perhaps more importantly, how to sack a bad solicitor. Once a working relationship has been established, defence campaigns can then act as a bridge between lawyers and their clients to the advantage of all parties.

Community defence campaigns can also do some of the work which solicitors rarely do – going out looking for witnesses, taking photographs and doing community “scene of the crime investigations”.

If a victim is not entitled to legal aid, and no solicitor is able to take on the case without charge, community defence campaigns are able to prepare a full legal defence case with a “McKenzie’s friend” available to help in court.

Investigating the police

There are two basic sources of information available on crimes against a person – the assailant and the victim. Witnesses are a secondary source of information. The same is true of police crime. The police officer responsible and the victim – whether assaulted or fitted up – are most likely to know what happened. By taking up individual cases of police crime as described above, community defence campaigns automatically start investigating the police. The more cases a campaign takes up, the better its information on the police.

This can be added to by storing every scrap of information which is available on the police – police publications, public statements, court reports, media reports, etc.

By rooting their work in individual cases of police crime, community defence campaigns can develop a coherent picture of the police. This provides an important basis for challenging the political power of the police in our communities. Hard factual information gives credibility to community defence campaigns and allows them to speak as community representatives.

Seeking redress

The victims of police crime want justice. They want redress. They want the individual officer responsible charged and put through the criminal justice system. They want them sacked. Unfortunately, none of this is likely to happen, and the best means of gaining redress is by suing the police for damages.

Civil actions are a legal means for gaining financial compensation for damages; they are not concerned with holding people to account for their actions. Civil actions are not brought against individual police officers, but against that officer’s employer, the force Chief Constable. The police are able to avoid court hearings by offering financial settlements which victims are obliged to accept. This means that civil actions only have a limited effect in challenging police crime. However, they are the most effective means of redress available and can allow victims to state their case against the police in open court.

Seeking redress through the police complaints procedure is unsatisfactory at every stage of the process. The principle problem is that the police investigate themselves. Police officers first have to be convinced that a crime was committed, and then relied upon to collect together the evidence against colleagues. At every stage of the procedure, victims’ motives are questioned and they can be accused of criminal intentions for pursuing their complaint. Very rarely do police complaints result in disciplinary action, much less in criminal proceedings. However, it is important to record complaints against the police through a solicitor or with the support of a community defence campaign.

Publicity

Community defence campaigns are necessary due to the absence of anybody else to challenge the police. Publicity is needed to inform people of what is happening An informed community is a strong community; people will know what to do if they are attacked by the police. The purpose of publicising police crime is to stop it, to pressurise the authorities into doing something about it.

A ROLE FOR TRADE UNIONS

Trade unionists are no strangers to police crime. Historically, the police have played the role of strikebreakers and some of the most excessive acts of police violence have taken place on picket lines. ACPO has planned how to deal proactively with mass picketing. They have looked at public order policing tactics around the world and devised their own methods of crowd control, as outlined in their unpublished public order manual. These methods were first put into practice during the 1984-5 miners strike at the Battle of Orgreave on 18 June 1984, when police cavalry charged pickets.

The basic strategy used by the police in these situations is to attack. There is no pretence at maintaining public order, containing disorder in a geographical area or protecting innocent bystanders. The purpose of police violence in these situations is to physically prevent a person from picketing, and persuade them that it is against their personal well being to picket in future.

It was during the miners strike that the political power of the police became most evident. ACPO effectively co-ordinated the government’s defeat of the strike by controlling the national movement of police squads against miners’ pickets.

The police will continue to use violence in the future to stop effective picketing. Trade unionists can organise against police crime in several areas:

- organising defence campaigns

- underwriting members legal costs

- providing courses on police crime, public order legislation and legal rights.

Organising defence campaigns

Trade union branches, councils, districts or regions can organise defence campaigns in the same way as any other community can.

Trade unionists need to organise themselves as effectively as the police when on picket duty. This means delegating responsibility for different tasks. Spotters need to watch police movements and keep written and photographic records, police violence and arrests need monitoring, first aid and legal support needs organising, and everybody needs debriefing when it’s all over.

It is legal for people to defend themselves against unlawful police violence, and to protect people near them. It is becoming increasingly necessary for people to have basic training in self defence in order that police violence can be resisted and to undermine the use of the police as strike-breakers.

In the event of arrests, trade unions can provide solicitors and co-ordinate defence campaigns. Fundraising can be organised to pay fines and to support prisoners and their families. Trade unions can also affiliate to local community defence campaigns and work with them to challenge police crime.

Underwriting legal costs

Defendants charged with minor offenses, such as obstructing the police and disorderly conduct, are often denied legal aid. Recent changes to the legal aid system means even fewer people are entitled to free legal representation.

Trade unions can support members who are victims of police crime by underwriting their legal costs. If union officers are properly informed of the details of a case, and if the victim is represented by a good solicitor, the victim should win the case and the court will award them costs. The union will not have paid a penny, and the victim will have felt better for knowing that, were they to lose the case, they would not have had to pay legal costs as well as any other penalty.

Civil actions are far more costly than criminal defence cases. However, with proper legal advice, and support from the membership, trade unions could also underwrite legal costs for civil actions by members.

Training courses

Trade union welfare officers can be trained to deal with police crime and to provide a service for members. Trade union solicitors can also be given specialist training in police crime.

The greatest need for training is for shop stewards. Courses can be organised on the 1986 Public Order Act and its particular reference to picketing laws, public order policing, basic legal rights and general aspects of police crime.

CAMPAIGNING FOR REFORM OF POLICE POWERS

At the moment the police are having everything there own way. Their mobilisation against the Sheehy report demonstrates their immense power. Not a word has been said in condemnation of their activities. Any other group of workers, manual or professional, would have been condemned and vilified by the media. It is as if nobody has the courage to stand up to the police. It is in the interests of democracy, or what is left of it, to have a public debate on police powers. This final section of the pamphlet contributes to that debate by proposing that some of the powers currently held by the police should be transferred to a separate body.

The problem of who polices the police is ageless. Regardless of the structure of society, the police will always have immense powers which are difficult to control. It is ridiculous to say dispense with the police, we are entitled to protection from anti-social elements in our communities.

The central role of the police is to maintain law and order. In unequal societies this means protecting the privileges of the rich and powerful against the poor and powerless. Any attempt to campaign for popular reforms to the police will operate with the knowledge that capitalism will only accept limited changes. However, 1990’s Britain is a divided state, even the rich and powerful are squabbling over Britain’s position in Europe. And one Home Secretary’s resolve to reform the police, may not be the same as another’s. Kenneth Clarke was committed to reforming the police and appointed his friend, Sheehy, to show him the way. When Clarke was promoted to Chancellor, and Michael Howard took over, his first decision was to allow the police to test US side handled extendable batons on the streets, which Clarke had opposed. Perhaps Clarke would not have caved in so quickly to ACPO and the Police Federation’s demands for changes to Sheehy’s recommendations.

It is necessary to fight police crime in our communities and it is essential that the growing political powers of the police are opposed.

Basis of police powers

The police’s basic powers are the powers to arrest suspects, investigate crime and charge suspects. Until the 1985 Prosecution of Offenses Act set up the Crown Prosecution Service in October 1986, the police also had the power to conduct prosecutions. Since the 1829 Metropoitan. Police Act established the police, they have steadily increased their political influence on the basis of these powers.

Although the police’s power to use coercive force is important, it is not fundamental. It is their power to take away a persons liberty, and then collect together the evidence to justify their imprisonment, which is awesome. The powers of arrest and investigation compliment each other and insidiously amplify police powers in an ever increasing spiral towards absolute power. We have now reached a stage where their powers have become counter productive to their role as a law enforcement agency, and even for maintaining public order.

The police’s monopoly over criminal investigations gives them control over information. That information has been used to envelop police operations in secrecy, to cover up criminal acts and form the basis of criminalisation programmes against whole communities and political and trade union activities.

Criminalisation of individuals and communities is the means by which the police have assumed immense political powers. The marginalisation of working class, Black, Irish and other minorities, allows the police to behave as an oppressive power in these communities. If they so wish, the police can criminalise any community they perceive to be a threat to social order. Thus miners became criminals during the miners strike, printers at Wapping and women at Greenham Common.

People are influenced by police stereotypes of criminals, unless experience tells them different. Most people are eager to accept police statements, because to do otherwise would be to question the very institution entrusted with their personal protection.

Individual police officers internalise these stereotypes and put them to practical use in their daily work. When a police officer stops a suspect, they do so on the basis of their own preconceptions of who is a criminal. By arresting that person, they add to the statistical definition of criminals. Even if a person is released without charge, or acquitted by a court, the police are in a strong position to comment. Thus, acquitted persons are not necessarily innocent. According to the police, they cannot convict criminals because the justice system is collapsing as a result of imbalances in favour of suspects. The police’s political powers have already undermined the presumption that a person is innocent. Arrested persons are now presumed guilty.

Individual police officers powers are frightening in communities of working class, powerless and criminalised people. Matters are made worse by the fact that the police have discretionary powers of arrest. There are many opportunities for officers to turn a blind eye in exchange for a favour. This leaves working class people insecure and dependent on the “good will” of police officers.

Significantly, the vast majority of cases of police crime involve individual police officers playing a central part in the arrest, investigation and charging of suspects. Many of these cases depend on the word of the police officer against the victim. The police officer responsible for an assault, a verballing or any other form of fabricated evidence, becomes the source of all information necessary for a criminal investigation and ultimately the conviction of the victim.

One power too many

Is it in the interests of justice that one person should have the power to accuse another person of a criminal offence, arrest that person, collect together the information to charge them, and then be the chief prosecution witness in a court of law which might result in their conviction and sentencing? These are the powers invested in individual police officers, and the police have sole responsibility for providing checks on this system. The situation raises serious constitutional problems with the office of constable.

On a general level, the entrusting of the powers of arrest and investigation to one institution has become the cause of the crisis in the police. There is a direct link between the police’s criminalisation programmes and their poor clear up rates of crime.

On the one hand, police resources are channelled into controlling criminalised communities and not fighting crime. On the other hand, the police’s control over information allows them to deflect public criticism and protect their economic privileges.

The decision to take away from the police the power to prosecute was made in the interests of efficiency, and for the prosecuting authority the CPS – to check the standard of evidence collected by the police.

The independence of the CPS has been questioned ever since it was established. But it is a very junior partner to the police, in history and powers. The CPS has to believe police officers and accept their advice to a great extent, otherwise it will disempower itself and become unable to prosecute.

It is proposed here that the separation of the power to prosecute away from the police is a step in the right direction. A further separation of the power to arrest from the powers to investigate and charge will significantly reduce the corporate powers of the police.

A separate criminal investigations service

By taking away the police’s powers to investigate crimes and charge suspects, police officers will be left with the power to make arrests. If an officer witnesses a criminal offence being committed, if a suspect is reported to the police, or information is forwarded to the police by an independent criminal investigations service, the police can arrest the suspect and hand them over to that separate body to investigate the alleged crime.

Police officers will continue to have responsibility for crime prevention and all other policing duties.

The existence of an independent criminal investigations service, with its own entrance qualifications, professional standards and associations, will automatically introduce a strong inquisitorial element into the criminal justice system. When the independent agency investigates criminal allegations, it will also look at the role of the arresting officer.

A criminal investigations service would have responsibility for interviewing suspects and witnesses, conducting all aspects of criminal investigations and charging suspects.

Criminal investigations staff will not have the power to make arrests – they will have to ask the police to do this. Neither will they have the legitimate right to use force, although they will investigate the police’s use of force.

The separation of the powers of arrest and investigation will introduce checks and balances to the criminal justice system. This is necessary not only for the protection of innocent people, but also for the protection of our communities from crime and for the establishment of effective law enforcement bodies.

ON OUR OWN

Working class life is a daily struggle for survival. People who have been attacked by the police want to get on with their lives without the extra worry of challenging police oppression. Politically minded people who get involved in community defence campaigns, for whatever reason, are hard stretched to deal with practical everyday problems, never mind considering ways of campaigning for police reform.

Somehow, we have to go on the offensive. For too long community defence campaigns have operated as pressure groups on the Labour Party, expecting them to take up the political issues raised by police crime. The Labour Party has turned its back on working class people, particularly black and unemployed working class people, who do not have “consumer power”.

Independent community organisations and militant trade unionists have to take on the task for themselves. We have the experience of police crime, we have a political understanding of the issues and we have credibility in our communities. Working class communities, and their representatives, have to strike out and seek alliances to campaign for reform of the police.

LURCHING FROM CRISIS TO CRISIS

1989

August: West Midlands Serious Crime Squad disbanded.

October: Guildford 4 released from prison by the Court of Appeal.

1990

February: Court of Appeal releases first West Midlands case from prison.

March: Fighting with police breaks out at anti-poll tax demonstrations throughout the country.

Trafalgar Square anti-poll tax riot.

July: Oliver Pryce killed by Cleveland police.

£50,000 damages awarded to Kevin Thorpe against Greater Manchester Police arising out of Manchester students’ demonstration against Home Secretary Leon Brittan in March 1985.

October: Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) publishes statement of common purposes as a response to widespread public criticism.

December: Seven Metropolitan Police officers are sacked for assaulting Gary Stretch in November 1987.

The Home Secretary, Kenneth Baker, announces 700 extra police officers across the country.

Metropolitan Assistant Commissioner Wyn Jones goes on extended leave pending investigation of unauthorised links with Asil Nadir.

Merseyside Assistant Chief Constable, Alison Halford, suspended from duty by Merseyside Police Authority after having complained to the Equal Opportunities Commission of sexual discrimination.

1991

January: John Edwards (W. Midlands case) conviction quashed;

Lord Lane rules that police officers can be cross examined about cases where juries have disbelieved their evidence.

PC Surinder Singh wins £20,000 compensation for racial discrimination against Nottinghamshire Police after he was refused promotion to the CID.

February: Wiltshire police pay out £28,000 damages to 18 people for damages arising out of the Battle of the Beanfield, Stonehenge, in June 1985.

March: Birmingham 6 released by the Court of Appeal. Home Secretary Baker announces the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice.

April: Vandana Patel murdered by her husband in Stoke Newington police station domestic violence unit.

Police Complaints Authority (PCA) triennial report shows record level of complaints;

PCA calls for changes to police disciplinary procedure.

May: 24 hour armed response vehicles (ARV) start patrolling London’s streets.

June: Four West Midlands officers cleared of perverting course of justice and perjury. Maguire 7 convictions quashed by the Court of Appeal.

July: 39 miners receive £425,000 damages from South Yorkshire police seven years after Battle of Orgreave in June 1984.

August: Ian Gordon shot dead by West Mercia police when carrying an unloaded shotgun.

Rioting in Oxford and Cardiff.

September: Rioting in Newcastle following the death of two joy riders in a police car chase.

November: Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield, senior officer at Hillsborough football disaster in April 1989, when 95 people died, retires from South Yorkshire police on medical grounds and avoids disciplinary action.

Four West Midlands police officers charged with conspiracy and perjury in connection with Birmingham 6 arrests.

Winston Silcott’s conviction for murder of PC Blakelock quashed by the Court of Appeal; Engin Raghip and Mark Braithwaite released from prison pending formal appeal hearing in December. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) announces that DCS Graham Melvin, in charge of Blakelock investigation, to be charged with conspiracy and perjury.

December: £55,500 damages awarded to Elizabeth Marks against Greater Manchester Police arising out of demonstration against Leon Brittan at Manchester University in March 1985.

1992

January: Ian Bennett shot dead by West Yorkshire police in Halifax when brandishing a replica gun.

February: Stefan Kiszko murder conviction quashed by the Court of Appeal.

Two Metropolitan police officers jailed for actual bodily harm.

March: OAP, Mrs Marie Burke, awarded £50,000 damages against Metropolitan police arising out of her arrest by Hackney police in January 1989.

May: Judith Ward released on bail by the Court of Appeal pending the quashing of her murder conviction.

Director of Public Prosecution, Barbara Mills, announces there will be no prosecutions of W. Midlands Serious Crime Squad officers.

July: Home Secretary Kenneth Clarke appoints BAT Industries chairman, Sir Patrick Sheehy, to lead an inquiry into police responsibilities and rewards.

Pearl Cameron sentenced to 5 years for conspiracy to supply crack cocaine. Revealed in court that she was supplied by a serving Stoke Newington police officer, later to be identified as DC Roy Lewandowski.

Darvell brothers murder convictions quashed by the Court of Appeal

September: Home Secretary Clarke calls for sacking of “poor performers” at Police Superintendents Association annual conference.

Devon Chief Constable, John Evans, tells the Bar Conference – police are “losing confidence in the criminal justice system” because of imbalances which favour suspects.

October: Frank Critchlow receives £50,005 out of court damages from the Metropolitan Police for a series of police raids against the Mangrove Community Centre in February 1988.

Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Sir John Woodcock, tells International Police Conference that police culture must change to restore public confidence.

November: Stoke Newington’s DC Roy Lewandowski receives 18 months prison sentence for theft from a murder victim’s home and misfeasance in a public office.

December: Two Humberside police doctors convicted of killing a remand prisoner by prescribing lethal drugs in Grimsby police station in September 1990.

ACPO launches 11 point statement on police ethics and principles.

Cardiff 3 murder convictions quashed by the Court of Appeal.

1993

January: Paul Condon takes over as Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis.

Police Complaints Authority announces seven W. Midlands Serious Crime Squad officers to face disciplinary charges and 102 to be informally disciplined.

£100,000 damages awarded to William King against Merseyside Police after he was assaulted at Tuebrook police station February:

Home Secretary Clarke refuses to refer Bridgewater murder convictions to the Court of Appeal.

Home Office study reveals 90% of female police officers have been harassed by male officers and as many as 800 have been sexually assaulted.

First of Stoke Newington cases at the Court of Appeal; Francis Hart and James Blake’s have their manslaughter convictions quashed.

Court of Appeal orders re-trial of Malcolm Kennedy for murder in Hammersmith police cell.

March: Four Stoke Newington drugs convictions quashed by the Court of Appeal.

Survey by the Independent newspaper shows the police are arresting and charging fewer suspects.

CPS announces that three officers in Darvell case are to be charged.

Condon informs House of Commons select committee that police officers are warning offenders because of the amount of paperwork involved in charging.

Home Secretary Clarke proposes a new two tier police disciplinary system for dealing with minor matters and serious misconduct.

April: Two more successful West Midlands appeals brings the total to 15.

May: Three former Surrey detectives are acquitted by a jury of fabricating evidence against the Guildford Four.

Court of Appeal quashes two more Stoke Newington drugs convictions bringing the total to eight.

June: Taylor sisters’ murder convictions quashed by the Court of Appeal.

New Home Secretary, Michael Howard, allows police to test US side handled extendable batons on the streets.

Metropolitan police pay out £87,000 damages to three trade unionists assaulted during the Wapping dispute in January 1987.

Ivan Fergus’ assault and intent to rob conviction quashed by the Court of Appeal.

Scotland Yard’s Operation Jackpot report into allegations of corruption at Stoke Newington police station sent to the DPP.

Government White Paper on police reform published.

Sheehy Report on police responsibilities and rewards published.

July: Royal Commission on Criminal Procedure report published.

Police cordon off City of London with “ring of rubber” and armed road blocks.

23,000 off duty police officers attend Wembley rally against the Sheehy Report.

Members of 40 police authorities hold a rally to condemn the White Paper on police reform.

August: Joy Gardner dies in hospital. Condon announces suspension of three SO1(3), specialist immigration squad, officers involved in her detention and suspends squad’s operations until an internal review is completed.

JOIN

HCDA:

Cost for individual membership £5 waged & £2 unwaged per year, and £25 per year affiliations for organisations.

TUSU:

Cost for individual membership £5 waged & £2 unwaged per year, and £25 per year affiliations for organisations.

Colin Roach Centre:

Cost for individual membership £5 standing order per month waged and £1 per month unwaged. Affiliations for organisations £50 per year.

Colin Roach Centre, 10a Bradbury Street, London, N16 8JN.

OTHER PUBLICATIONS

HCDA:

A peoples’ account of the Hackney Anti-Poll Tax Demonstration on March 8th 1990. £2 (photocopied).

A Crime is a Crime is a Crime. A report into police crime in Hackney presented to the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice. £1

Fighting the Lawmen. On Stoke Newington police’s drug dealing: containing personal accounts and how HCDA exposed the scandal. £1.

TUSU:

A trade union approach to access for people with disabilities. £1.

Employment rights at work. In English and Turkish. 50p.

Available from HCDA or TUSU, Colin Roach Centre, 10a Bradbury Street, London N 16 8JN.

Phones: HCDA – 071-249 0193 TUSU – 071-249 8086

Pingback: HCDA – On The Border Of A Police State, 1993 | The Radical History of Hackney