Alongside the generalised anti-racism of the Black Lives Matter protests, it has been great to see specific demands emerge. Some of these have been very practical, such as the removal of colonial or racist statues or support for campaigns around deaths in custody such as the United Friends and Family Campaign. Others, such as defunding the police, would appear on the surface to be much more idealistic or longterm.

For some people, challenging the role of the police is strictly off-limits. A token reform here and there, alongside a rabid competition to give the cops as much money as possible, is what mainstream political debate looks like in the UK in the 2020s. But a growing number of people are not satisfied by that. Here is a handy four minute introduction:

Defunding the police is not a new demand and perhaps previous campaigns can inform the current debate.

In February 1983, Hackney Council’s Police Committee resolved to withold the Council’s £4 million donaton towards the cost of the Metropolitan Police – “the precept”. This was put to a full meeting of the Council on 23rd of February which adopted the following motion:

That the Council take whatever steps are open to it to withold the payment of the police precept both as an expression of anger at the state of policing in Hackney and with a view to bringing home to the Government the community demands for an independent inquiry into policing in Hackney.

Quoted in Policing in Hackney 1945-1984

Hackney People’s Press (#87 Feb 1983) quoted Councillor Patrick Kodikara:

“30 per cent of the ratepayers of Hackney are black. Why should the Council pay the police to practise repression on us?”

The motion was passed – with all of the Labour and Liberal councillors voting in favour – and all of the Conservative councillors voting against.

The next issue of Hackney Peoples Press (#88 March 1983) was a bit more cynical:

“The Council’s statement of intent not to pay the precept of £4 million this year is just a gesture. The law does not allow them to withold the money, and, this year at least, they are not going to break the law. But by making the gesture they are indicating that they are paying up under protest, and are joining other London boroughs who have already reached the same conclusion: they pay over ratepayers money each year to the police yet London is unique in the country in not having an elected police authority”

And sure enough, the Council was told by its legal advisers in March that it could not legally withold the money and the precept was paid – I assume in time for the next financial year in April 1983.

The Policing in Hackney book mentions the Council’s decision generating a great deal of media attention, which I’ve not yet been able to track down, but imagine was suitably unsupportive and outraged.

This was all spun by Hackney Central MP Clinton Davis in Parliament:

“My own local authority may be very frustrated—sometimes with justification—by some of the actions, or the inaction, of the local police. The suggestion of the withdrawal of the police precept is, however, an empty but unacceptable gesture which increases the anxiety of many of my constituents—particularly the elderly—that the police are suddenly to be withdrawn. But of course that will not happen.

When I spoke to Councillor [Brynley] Heaven, the chairman of the police liaison committee, he readily agreed that it would not happen. It is a gesture—a vote of no confidence in the police—but I do not believe that such a gesture is justified by the circumstances. If we are to make constructive criticisms about the police, as sometimes we must and as I do today, it does not add to the authority of those who support such criticism to join in every meaningless gesture and every attack on the police.”

Two years later, Hackney Council would verge closer to breaking the law when it refused to set a “rate” (essentially the equivalent of Council Tax now) in response to the Thatcher government’s efforts to restrict local government spending.

This incident of almost defunding the police did not emerge spontaneously from a “loony left” council with nothing better to do. It was the culmination of years of terrible policing resulting in a number of community campaigns…

Background to the motion to defund the police

(This timeline covers the most significant events. Examples of the much more common day to day police corruption and harassment are covered in Chapter 8 of Policing In Hackney).

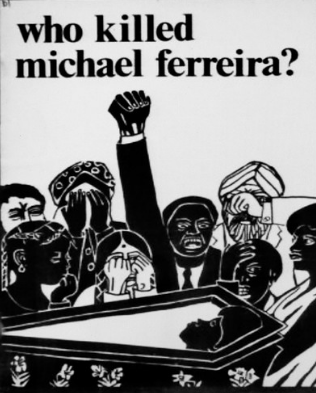

December 1978: Black teenager Michael Ferreira is stabbed during a fight with white teenagers in Stoke Newington. His friends take him to the nearby police station, where the cops seem more interested in questioning them than assisting Michael, who dies of his wounds before reaching hospital.

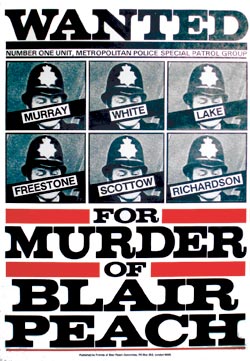

24th April 1979: Hackney resident Blair Peach is killed during a protest against the National Front in Southall. 14 witnesses saw him being hit on the head by a policeman. It was generally understood then, and is widely believed now, that Peach was killed by an officer from the notorious Special Patrol Group. The SPG’s lockers were searched as part of the investigation into the death, uncovering non-police issue truncheons, knives, two crowbars, a whip, a 3ft wooden stave and a lead-weighted leather cosh. One officer was found in possession of a collection of Nazi regalia.

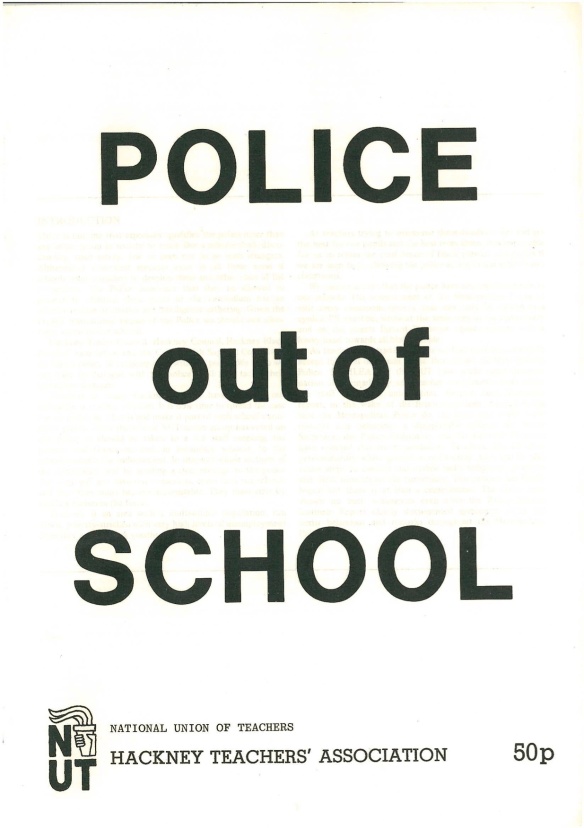

The failure of the police to properly investigate the murder of Blair Peach – and their general harassment of youth, led Hackney Teachers’ Association to adopt a policy of non-cooperation with the police. This is documented in the excellent Police Out of School which is available in full on elsewhere on this site.

November 1979: A conference of anti-racist groups in Hackney calls for the repeal of the “sus” laws that allow police to stop and search anyone they are suspicious of. In 1977 60% of “sus” arrests in Hackney were of black people – who made up 11% of the borough.

February 1980: Five units of the Special Patrol Group began to operate in Hackney with no consultation. When the Leader of the Council criticised the police for this, Commander Mitchell responded by saying “I don’t feel obliged to tell anyone about my policing activities”.

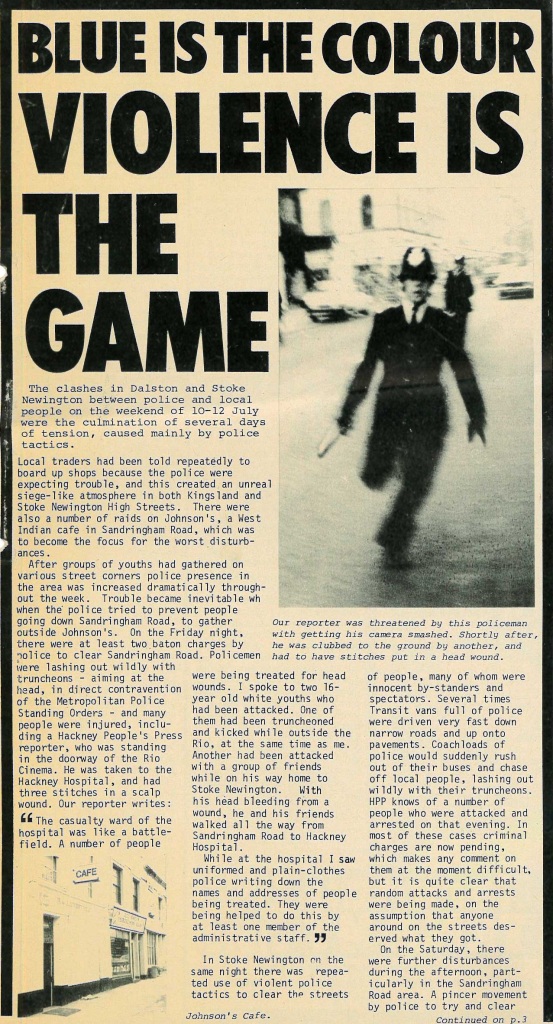

July 1981: Riot in Dalston. Searchlight magazine blamed Commander Mitchell’s hardline policies for the incident.

Also in 1981: Lewisham Council threatened not to pay the police precept.

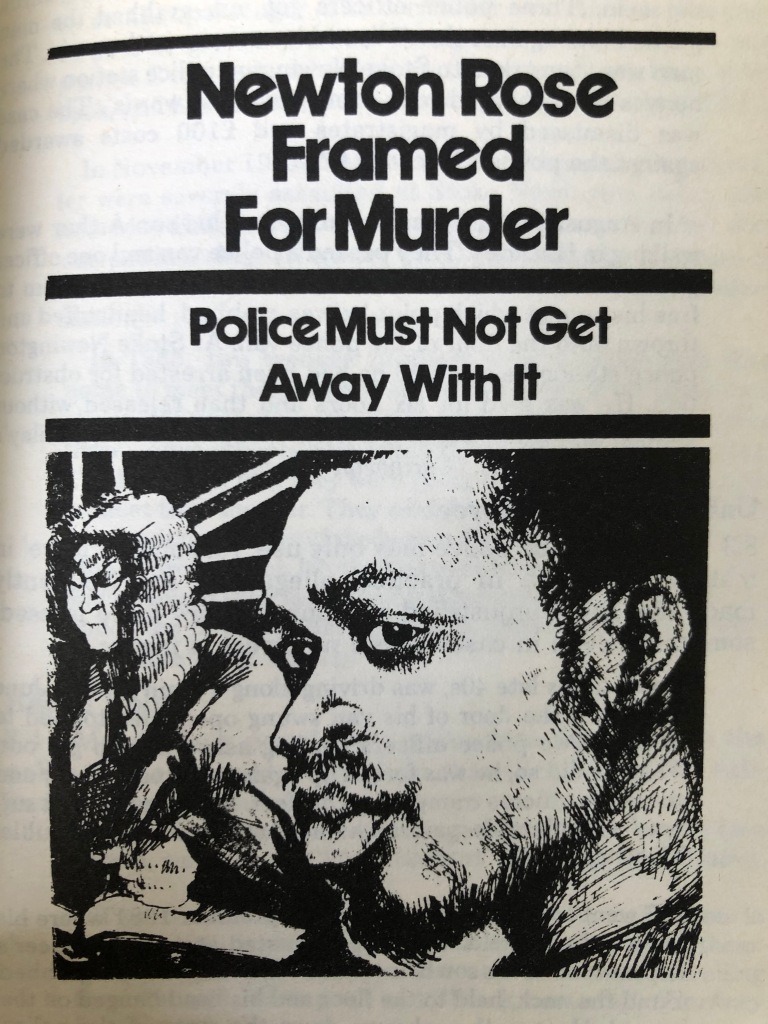

December 1981: Newton Rose falsely convicted for the murder of Anthony Donnelly, a Clapton resident with National Front connections. A successful campaign results in Rose being freed in 1982 becaue of a “grave material irregularity” in the trial.

April 1982: David and Lucille White, an elderly black couple, are awarded £51,000 damages for “a catalogue of violent and inhuman treatment” by Stoke Newington police.

July 1982: First meeting of Hackney Council’s new Police Committee, set up to consider and monitor policing in the borough – and make the police more responsive to local needs. The committee replaced an informal police liaison group which met in private and alternated its chair between the police and the council. The committee’s meetings were public and chaired by its members. A Support Unit was also established which monitored crime and policing and published reports critical of police powers.

12 January 1983: Death of Colin Roach by gunshot in the lobby of Stoke Newington police station.

Roach’s parents are treated appallingly by the police. Demonstrations organised by the Roach Family Support Commttee (RSFC) outside the police station result in numerous protestors, including Colin’s father, being arrested.

Ernie Roberts, Hackney MP, made a statement on the public’s concern about the breakdown of community/police relations as well as his support for a public inquiry into the death of Colin Roach. The Greater London Council funded the Roach campaign to the tune of £1,500 shortly afterwards. There was outrage in the press at this use of public money to fund what they saw as “cash to fight the police” and “fostering discontent among black people”.

February 18 1983: Colin Roach’s funeral.

RFSC instigates its “break links campaign” and writes to all Hackney Councillors asking them to:

- vote to withold the police precept

- hold a vote of no confidence in Stoke Newington police

- agree to break all links with the police unless and until an independent public inquiry into the death of Colin Roach was held.

Hackney social services workers put pressure on thier union – Hackney NALGO, which passes resolution calling on members to “break links” with the police.

Meanwhile, slightly east of Hackney:

“Tower Hamlets Council is to be asked on Tuesday to follow the Hackney Council example and consider witholding the Metropolitan Police rate precept. The Newham Monitoring Project is to call upon the local council to do the same unless an independent inquiry into Forest Gate police station in Newham is set up.

Mr Unmesh Desair, the project’s full time worker, yesterday described the station as a “torture chamber”.

The Times, February 24, 1983

Afer the fuss about non-payment of the precept had died down, other aspects of the campaign were still live issues.

In May 1983 Hackney South and Shoreditch MP Ronald Brown, bemoaned the continuation of the “break links” campaign in Parliament, singling out Hackney Council for Racial Equality:

Since 10 January, the new police commander has tried desperately to establish contact between the police and that organisation. Recognising the complaints about the police in London, particularly in Hackney, as well as the difficulties in Hackney as a result of the tragedy that occurred, he has endeavoured to re-establish a relationship with the community. He has approached every group in an attempt to get a dialogue going.

What kind of response did he get from the Council for Racial Equality? In a letter of 21 February it said:

I am writing on behalf of Hackney Council for Racial Equality Executive”—not the council, but the executive—who have asked that you give instructions that the local home beat officers covering the HCRE Mare Street office, the HCRE Family Centre, Rectory Road, no longer call”—that phase is underlined—at either of these offices unless HCRE gives a specific call to the police.I trust this will be acted on with dispatch.That was signed by the community relations officer. That destroyed the relationship between the beat policemen and the community in the two areas. By common consent, that relationship had proved valuable. That one letter wiped out that relationship.”

The publication of Police out of School in 1985 generated a further furore and also a PR campaign from the police. The campaign and police response are covered in this great news report from the time:

Conclusion

Calls to defund the police in the 1980s need to be seen as the tip of the iceberg of wider community resistance. This made it much harder to dismiss the idea of defunding as “gesture politics”.

In Hackney, the antagonism between the police and community only intensified after this, with corruption at Stoke Newington police station expanding to include further deaths in custody and police officers getting involved with drug dealing, amongst other crimes. In the 1990s this would be met head on by Hackney Community Defence Association.

I am shit at reading budgets, so please laugh at me, but it looks to me like:

Total council tax donations to Greater London Authority for the year 2020/2021:

£1,010,907,032.68

Amount of this which goes to Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime:

£767,054,360.26

So that’s about 75% of the total.

Hackney’s donation to the GLA would seem to be £24,701,359.02

75% of that is roughly £18 million.

(A purely inflationary rise from the £4m in 1983 to now would be £11.59m, but you would also need to factor in the expanding population of Hackney in that time – according to Wikipedia it was 179,536 in 1981 and 280,900 in 2020 which is an increase of 56%.)

A question worth asking is: would spending this £18 million of our money on other things be better at reducing crime and harm?

Sources and Further Reading

Hackney Peoples Press (various issues)

Police Out of School (Hackney Teachers Associaton, 1985)

Policing In Hackney 1945-1984: A Report Commissioned by the Roach Family Support Committe (Karia Press & RFSC 1989)

Policing London #2 September 1982 (GLC in the Police Committee Support Unit)

John Eden – “They Hate Us, We Hate Them”: Resisting Police Corruption and Violence in Hackney in the 1980s and 1990s (Datacide #14 2014)

Paul Harrison – Inside The Inner City (Penguin , 1983)

Michael Keith – Race, Riots and Policing: Love and Disorder in a Multi-racist Society (UCL Press, 1993).

Pingback: Monument plan for H Block prisoners in Hackney (1981) | The Radical History of Hackney

Pingback: Three days of rioting kick off in Dalston and Stoke Newington, 1981 | past tense

Pingback: Today in London policing history, 1983: Colin Roach dies in Stoke Newington Police Station | past tense

Pingback: Watching us watching them: Spycop thoughts on police accountability in 1980s Hackney | The Radical History of Hackney

Pingback: Hackney Peoples Press 1973-1985: 96 issues online | The Radical History of Hackney

Pingback: Review | White Riot | rs21

Pingback: Review | White Riot – report

Pingback: Review | White Riot – 🚩 CommunistNews.net