Content warning: archaic racist and sexist language.

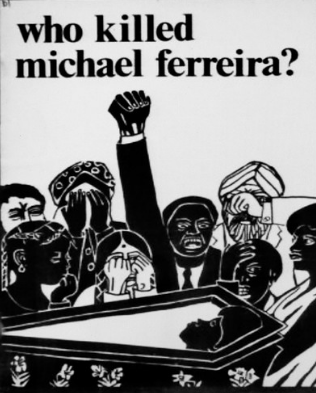

The racist killing of Michael Ferreira in December 1978 and subsequent protests inspired some local secondary school children to write a play. This was then published anonymously as a pamphlet.

Teacher, writer and activist Chris Searle later explained that the play had been written collectively by his pupils at Langdon Park School in Tower Hamlets:

“We acted out the play in the classroom, and as the campaign grew in East London, to publicise and protest against the circumstances of Michael Ferreira’s death, we decided to use the play in whatever way we could to make a contribution.

I had already met Michael’s mother and told her about the project, and she too thought it would be a useful idea to publish the short play as a pamphlet for young people. I interviewed her and learned some information about her son… and this became the basis for a short introduction.

The play… became a useful vehicle for informing people, in a narrative and dramatic form, about what happened to Michael and his friends.”

Chris searle

Searle had previously caused a furore in 1971 when he published a collection of poems by pupils at John Cass Foundation and Red Coat School in Stepney. The poems were deemed inappropriate and Searle was sacked. Kids at the school then went on strike, which along with some pressure from the National Union of Teachers, led to his reinstatment.

So that probably explains the anonymity of this play’s publication, which appears to have been well justified. When “Who Killed Michael Ferreira?” was included in an anthology in the 1980s, Searle was denounced in Parliament and the play was mischaracterised as being about “a gang of black youths”.

The full text of the booklet follows below. The biography of Michael and a related newsclipping from the last page are placed at the beginning here instead. A scan of the booklet is available at archive.org.

As Chris Searle says, the play was written by “a multi-racial group of 14 year olds” in 1979 and the words used by the protagonists reflect this: “their dialogue is steeped in sexist banter, there is no attempt to idealize them as characters or sanitize their speech.”

Much of the information above is taken from Chris Searle – None But Our Words: Critical Literacy in Classroom and Community (Open University Press, 1998). This also includes many interesting insights into how the pupils worked together to create the play (and a fascinating chapter on the Stepney incident too, amongst others).

With thanks once again to Alan Denney.

Notes:

There are a couple of references in the text that warrant further explanation in 2022:

Chapel Street Market, Islington – This was one of the National Front’s main pitches for selling their literature – as well as intimidating the local community – at the weekend (another pitch being Brick Lane). There is more informaton about this (and the effective physical resistance to it) in Anti-Fascist Actions’s The Battle For Chapel Market, republished at Libcom.

‘SUS’ – legisation that allowed the cops to stop, search and potentially arrest people on suspicion of them being in breach of section 4 of the Vagrancy Act 1824. It was widely used against black youth, and this is often cited as one of the factors that led to widespread rioting in the UK’s urban areas in 1980 and 1981.

MICHAEL FERREIRA, 1959-1978

Michael Ferreira was born in Stanleytown, Guyana in 1959. He died after being stabbed in the liver by a white youth along Stoke Newington Hight Street in December 1978.

Michael, the third child, grew up with his three sisters in the region of Berbice, the scene of a great slave revolt in the eighteenth century. Guyana is drained by huge rivers and covered in tropical forests and savannah, with a cleared coastal area of cultivated land, rice fields and small villages. In the yard of Michael’s parents’ house there were chickens, turkey and hogs, paw-paw and coconut trees- a far cry from the brick and concrete of his later home, Hackney, East London.

When he was six his mother emigrated to Britain, and gradually other members of the family, including his three sisters, left to join her. Michael went to live with his aunt in McKenzie, a mining town inland in Guyana, hacked out of the thick equatorial forest. There he continued his childhood, living near the bauxite mines and spending many happy hours fishing in the rivers and streams that abound there.

His family say that he was a happy, open, fun-loving boy at this stage of his life, even though he was always very small for his age. He never grew much higher than five feet, even when he reached his late teens. But his childhood in McKenzie was cut short in 1971, when he left Guyana to join his mother and sisters in Hackney. When he arrived in such a new environment his personality seemed to close up, and he became quieter and much more shy and withdrawn. It was only after he finally left school and in the last three years of his life that the liveliness and self-confidence of his childhood began to emerge again.

His years at Downsview School, Hackney, were marked by a growing interest in mechanics and practical subjects, and when he left school at 16 he went straight into a job as a motor mechanic. He had a dream of one day opening his own garage. He was never involved in any violence and had a pacific character that always sought to heal conflict rather than provoke it. Even when faced with the knife of the racist attacker he did not think of fighting, but stood his ground trustingly.

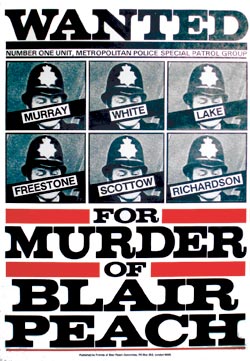

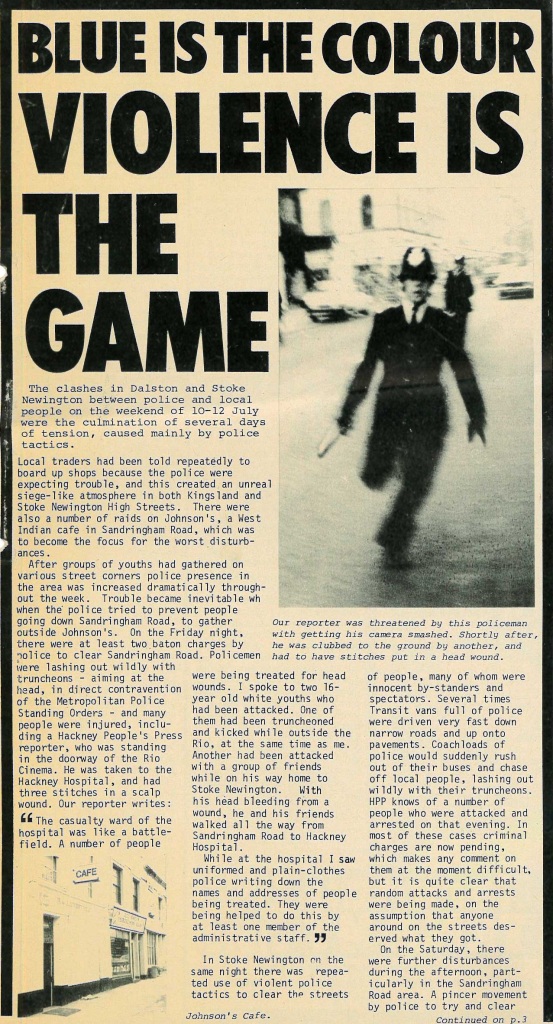

Michael’s horrific death, in the face of police connivance and delay, was not an isolated incident. We remember the brutal hounding of David Oluwale, West African, in Leeds in 1969, and the racist gibes and fists of the Leeds police that caused his persecution and death. We remember the young London Irishman, Stephen McCarthy, his head smashed by police against a steel bus stop in Islington in 1971. We remember the lack of inclination of the East London police to defend and support Asians like Altab Ali – murdered on the streets of Spitalfields last year. And we remember Kevin Gately, killed at Red Lion Square, and Blair Peach, an anti-racist teacher from a Bow school, clubbed to death at Southall by the Special Patrol Group.

How much of the reality of a peaceful, five feet one inch black teenager knifed by young white thugs who towered over him and left to bleed to death by London police, truly emerged in the courts? Clearly very little. The truth is still clear: despite a toothless and impotent Race Relations Act, overtly racist groups like the National Front and British Movement give open encouragement to white youths to attack and kill black people on the streets, and they still have the full freedom and protection of the law to continue to prompt them. British racists who publically talk of genocide and ‘one down down, a million to go’ after the murder of an Asian youth are acquitted and congratulated by British judges. The mentality of gas-chambers is upheld and promoted. Michael’s assassin, from the evidence presented in court, carried a knife for the express purpose of ‘having a go at coloureds’ and was a known associate and newspaper seller of the National Front. And yet the court and all-white jury declared that there was no racist motive for the killing.

This short play was written collectively by secondary school children shortly after Michael’s death. They never knew Michael or his friends or his killers, and so clearly the play is their attempt, through their imaginations, to understand the incident and and the characters, rather than a strict documentary drama. The children who wrote the play have their family origins in England, Scotland. Ireland, St Lucia, St Vincent, Barbados, Jamaica, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Somalia, Morocco, Turkey, Cyprus and Mauritius. They are a part of the British People who will live and work to carve out a new life in London, and carve through the bigotry and racism that exploits and threatens us all.

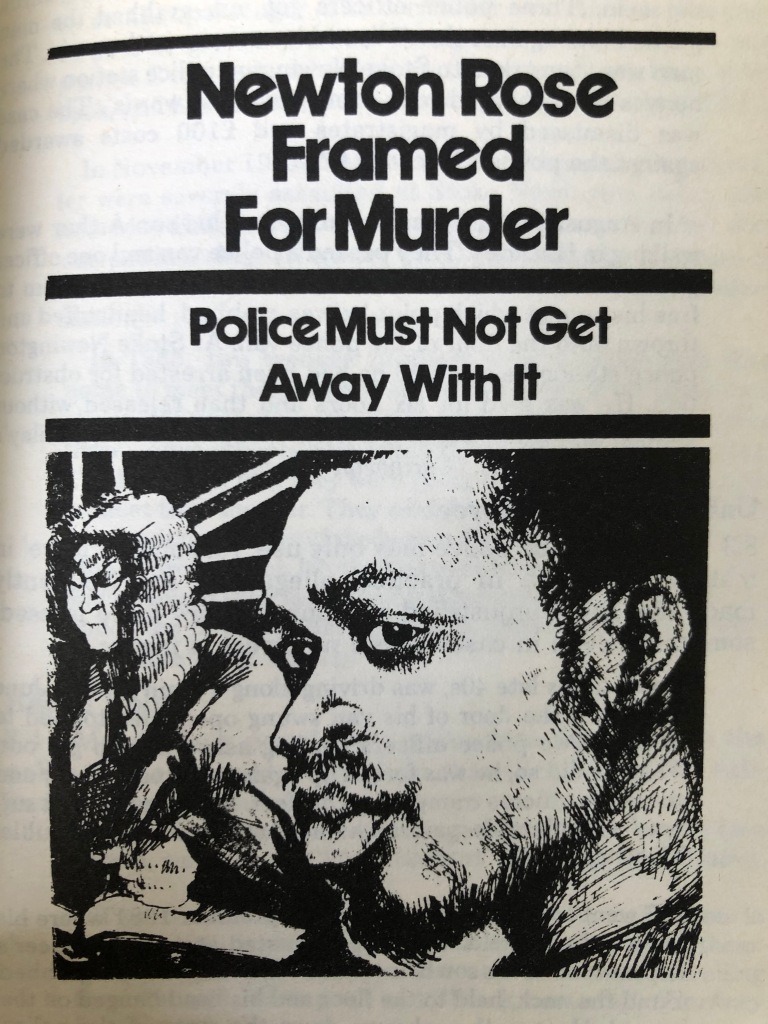

‘NO JUSTICE’

“There is no justice in this land for Black people.” That’s the way Mrs Ann Moses, the mother of 18 year old Michael Ferreira of Hackney, East London who was stabbed to death by a white thug late last year, reacted to the 5 year sentence passed against her son’s killer by Justice Stephen Brown at the Old Bailey Court, last week.

All White Jury

An all-white jury sitting in judgement of the two accused men, Mark Sullivan, 17 years old and a market street trader of Kingsland Road, Shoreditch, East London and 18 year old James Barnes a meat porter of William Penn House, Shipton, Bethnal Green, returned a guilty verdict on Sullivan and set free his accomplice, Barnes,

The court was told that both men had been involved in a fight with Michael and a group of his friends in Stoke Newington Hight Street late last year when Michael was fatally stabbed by Sullivan. Half an hour after the stabbing Sullivan and Barnes were picked up by the police for questioning and admitted that they had committed the crime. A few minutes after Michael was stabbed, he was taken to St Leonards Hospital in Hackney where we was announced dead on arrival by doctors.

A mass demonstration was organised by the Hackney Trades Council and Black organisations in the area following this and other murders of Black people in East London, with the protestors claiming that supporters of the racialist party, the National Front, were responsible for Michael Ferreira’s death. In the trial however, the judge dismissed any connection with the National Front in the murder and in passing sentence on Sullivan said:

“You used a deadly weapon on a completely harmless young man who had done you no wrong.”

“It must be made plain to all those who go forth with weapons of this kind that they can expect serious punishment if they use them.”

I interviewed the bereaved mother at her home in Rushmore Road, Lower Clapton, last Saturday, and with tears streaking down her cheeks, she said: “I am completely flabbergasted with the sentence. I cannot see Black people given proper justice in the courts of this land. I myself felt like dying when [I] heard that the judge had sent that “murderer” down for just five years. I expected that Sullivan deserved to get 14 years for killing my son.”

Mrs Ann Moses was also very critical of the racial composition of the jury and cast doubts on the integrity of the judiciary for their failure to include a black in judgement in cases of this nature.

After the trial in which the public gallery was filled with supporters of the National Front, a roar whent up in the court room when the judge announced the verdict.

Who killed Michael Ferreira?

Michael Ferreira, a West Indian youth, died during the early morning of December 10th, 1978, in Stoke Newington, East London.

This short play is a collective attempt, written by a class of third year school students from an East London secondary school, to trace the events leading up to his death.

Characters

West Indian Youths:

- George

- Dexton

- Michael

- Delroy

- Leroy

- Tony

White Youths:

- Mark

- John

- Peter

3 policemen

2 ambulancemen

Mr and Mrs Daniels: Parents of Tony and Leroy

Mr and Mrs Ferreira: Parents of Michael

Mortuary attendant

Narrator

PROLOGUE

The evil wings of racism have once again

spread over this country,

The evil that has brought fear—

and I warn my black brothers

stay clear!

The police are racist

the employers are racist

the bosses won’t give you a job

if you’re an Asian called Abdul

or even a West Indian named Bob!

The police pick on us

because we’re black,

they nick us on ‘SUS’

they beat us up

insult us…

Now, there’s a dirty word—N.F.

and when the racists insult us

we have to act deaf.

But we’re not going to act deaf no more

because we know the N.F.

are rotten to the core!

There have been demonstrations

against the N.F.

but that won’t do no good!

The racists are cowards,

they’ve got no sense—

just young hooligans.

If you’re black, brown or even colourless

but red—

the N.F. want you dead!

Get together, let the people know,

there’ll be no fun if the Nazis grow!

WHO KILLED MICHAEL FERREIRA?

SCENE 1: Stoke Newington High Sheet

NARRATOR: The time is 1.15am. A group of youths are walking home down Stoke Newington High Street from a late night disco. The date is December 1978.

Enter George, Dexton, Michael, Delroy, Leroy and Tony. They walk a group down the street, talking together and sometimes staring into lighted shop windows.

LEROY I can’t wait to get home.

MICHAEL Hey—did you see those girls in the corner?

DEXTON Yeh, did you see that one with the big tits?

GEORGE Yeh—weren’t they massive?

DEXTON Monica looked great, didn’t the?

TONY She’s really good-looking—I could fall for her myself.

DELROY Keep your eyes off man, she’s mine!

GEORGE What about that girl with the red straights on – she had a right old pair of knockers.

LEROY But it was a great disco—wasn’t it?

GEORGE Hmmm…. not bad.

LEROY What do you mean ‘not bad’—it was brilliant.

GEORGE It was quite good, but the beer was too dear.

TONY Well—maybe the disco wasn’t very good, but the birds were.

Delroy stops at a shop window.

DELROY Hey, look in this sports shop here. They’ve got those new Adidas boots – hey George, what do they call them now?

GEORGE I don’t know!

TONY They’re called ‘World Cup’ 78′.

MICHAEL Hey—Tottenham lost 7-1 today.

LEROY That’s a lie—who was it against then?

MICHAEL The greatest team in the world.

LEROY Who’s the greatest team in the world then? I thought it was Tottenham?

MICHAEL Tottenham? Bunch of wankers! Liverpool are the best team in the world!

DELROY Hey- I like that track suit.

LEROY Do you lot know what the time is? It’s ten past one already.

MICHAEL Is it? God, my mum’s going to be worried about me man.

DELROY Look-I’m running, otherwise I’m going to get hit man. You coming?

TONY Yeh—I’ll come on with you.

LEROY Me too.

MICHAEL All right, we’ll walk on behind you then.

TONY Okay—see you!

Delroy, Leroy and Tony walk on ahead.

Enter three white youths, walking along the other side of the road, opposite George, Dexton and Michael.

Mark, John and Peter begin to signal and hoot at the boys opposite them.

LEROY Hey, who are that lot over there?

GEORGE I don’t know them, do you?

MARK (Shouting across to the other side of the road.)

Hey, look at that one (pointing to Michael) he must have come from the deepest part of the jungle by the looks of it.

PETER Pity there’s no trees here for him to swing on!

JOHN Ahhhh—there’s no bananas neither.

PETER Funny—I’ve never seen a monkey fight, have you?

MICHAEL (Shouting back to them) Come on then you….

DEXTON No it’s not worth it, Michael. We’ve already had that trouble with the police.

GEORGE Yeh, we don’t want no trouble with them.

DEXTON All right then, let’s move on a bit.

GEORGE (Pointing) I know them boys. I’ve seen them down Chapel Street Market giving out National Front leaflets.

MARK Oi-you black bastards! Get back to your own country before I kick you there!

DEXTON You know, I feel like going over there and smashing their faces in.

GEORGE No, we can’t do that. That’s asking for it. We’ve had enough trouble with the cops – you remember that SUS business?

PETER All you blacks are chickens! If you had any guts you’d come over and fight, you bloody monkey-chasers!

DEXTON Why don’t we go and do them?

GEORGE Cool it man—the Babylon shop’s just down the road.

DEXTON No—let’s go and teach them a lesson.

MICHAEL Look—it’s not worth it, is it? They’ve done us enough times for SUS, we don’t want no more trouble.

MICHAEL But don’t walk any faster because of them or they’ll think we’re a bunch of shitters.

George, Michael and Dexton walk on up the street.

JOHN Yah, look at you lot, running up the road already.

Going home to your mammies are you?

GEORGE Come on, let’s let it.

MICHAEL No, don’t run – just ignore them.

DEXON But they’ve got to learn not to provoke us like this, man.

MARK You bloody niggers! Come and fight us you load of wankers!

GEORGE Come on, don’t take no notice, we don’t want no trouble.

MICHAEL Look – we’ve had enough of the SUS, haven’t we? Just keep walking normally.

The three white boys cross over to their side of the road. They start to sing ‘Go Home You Blacks, Go Home!’

MARK Hey, come on! Three onto three’s a fair fight.

JOHN Yeh, come on you peanut-heads!

DEXTON (Turning) Come on then, come on!

MICHAEL Knock it off Dexton! Keep on walking.

DEXTON No man! They want a fight so they’re going to get a fight – I’m not chickening out of this one.

MICHAEL You’re giving them just what they want, you berk! They’re trying to get you into trouble. Don’t take no notice of them.

DEXTON We could beat them easy.

MICHAEL Look—we’re not chickens, we just don’t want no more trouble.

MARK Come on peanut-heads, what you waiting for?

PETER What? Expect a black to fight back? You must be joking!

JOHN Right—come on, let’s get them!

John, Peter and Mark jump on George, Dexton and Michael.

DEXTON Right—you started it, now you’re going to get it.

GEORGE Watch that one there—he’s got a knife.

JOHN (To Mark) Come on, put the knife away Mark!

DEXTON Look out Michael, he’s coming at you!

JOHN Put that bloody knife away Mark. We don’t need that.

DEXTON Michael, look out!

Mark runs at Michael with the knife. He stabs him in the liver.

MICHAEL AE.E.E.E.E.E.

DEXTON George—he’s bloody knifed him!

GEORGE Bloody hell—Michael!

JOHN (To Mark) I told you to put that bloody thing away. Now look at what you’ve done. Let’s get the hell out of here!

MARK Yeh, you’re right—let’s split!

Mark, John and Peter run off up the road. Michael collapses on the pavement.

DEXTON Michael—come on, you’re all right really, get off the floor.

GEORGE Come on, get up Michael.

MICHAEL Ah-h-h-h-h-h-h…..

DEXTON Bloody hell, that’s all we need now.

GEORGE Dexton, help me get him up. (They support him on to his feet.) We’d better get him to the hospital.

MICHAEL Bloody hell, it hurts…. I’m bleeding all over.

Delroy, Leroy and Tony tun back to see Michael.

TONY What’s going on?

DELROY Hey, what happened to Michael?

GEORGE One of them bloody skinheads knifed him.

TONY Don’t muck about—now, what happened?

GEORGE They stabbed him, I tell you!

DEXTON Don’t stand there chatting—look, he could be bleeding to death.

TONY Where’s the nearest call box? He needs an ambulance.

DELROY It’s just round the comer.

TONY Let’s go then. (Tony and Delroy run off.)

DEXTON (Supporting Michael) It’s all right Michael, we’re going to get the ambulance for you.

GEORGE Yeh, it’ll be here in no time.

MICHAEL Ah-h-h-h-h-h-h it really hurts now.

Tony and Delroy run back, breathless.

TONY The bloody ththg was broke.

DELROY Some vandals smashed the phone in.

DEXTON That’s all we need, isn’t it?

Michael groans, almost continuously.

GEORGE What are we going to do then? He’s really hurt.

LEROY The nearest phone’s in the police station.

GEORGE What—take him to the Babylon shop? Once we’re in there we’ll never get out.

LEROY What choice have we got—look how he’s bleeding.

GEORGE All right then, let’s get him down there.

MICHAEL (Almost delirious) Yeah…. come on…. take me there.

DEXTON Oh Christ, I suppose we’ll have to.

LEROY Bloody hell, I hope it’s all right.

They support Michael to the steps of the police station. They half lift and half drag him up the steps.

GEORGE Come on all of you. Let’s get him up here and find a phone.

End of Scene I.

SCENE 2 In Stoke Newington Police Station

The boys enter the police station. There are two uniformed policemen behind the desk.

POLICEMAN 1 What do you lot want?

POLICEMAN 2 What have you been up to?

POLICEMAN 1 Yeh—what’s going on?

GEORGE Please…. look, our friend’s bleeding. Can we call an ambulance?

POLICEMAN 1 Hold your horses, I want to know exactly what’s going on here.

GEORGE There ain’t time for that—look how he’s bleeding.

POLICEMAN 1 Shut up – now first of all, give us your names and addresses.

GEORGE Look, just phone for an ambulance first, we’ll tell you all about it afterwards.

DEXTON Yeh, he’s hurt, you know.

MICHAEL Please…. help me…. phone for an ambulance.

POLICEMAN 2 Keep quiet son, we’ll attend to you in a minute. I’ve got to take a statement first.

DEXTON Look, I can tell you very quickly. In a few simple words. We were jumped on by three white kids. One of them stabbed him.

OFFICER 1 Where was this?

DEXTON Opposite the park.

POLICEMAN 1 Did you recognise any of them?

DEXTON No, but we’ve seen the all down Chapel Street handing out National Front leaflets. Now come on, please call us an ambulance.

MICHAEL (Groaning) Please…

Enter a third policeman.

POLICEMAN 3 What’s going on here?

OFFICER 2 These boys have been starting trouble.

DEXTON What? We didn’t do nothing, they set on us. Now are you going to phone for a bloody ambulance?

POLICEMAN 3 Watch your language with me Sonny. Now, have you lot been in any trouble before?

DEXTON We were picked up once for SUS.

POLICEMAN 3 Ahhh! So you started a fight eh? Picked on some white boys eh? Then you got the worst of it and come here with your lies about other kids?

GEORGE (Pushing forward) Look – can’t you see how our friend is bleeding. Send for an ambulance!

TONY Yeh—if he gets any worse, you’re to blame copper!

POLICEMAN 3 Be very careful son. Now, what time did this so-called attack occur?

DEXTON I don’t know—about half-past one.

POLICEMAN 3 Oh yeh? And what were you little boys doing out at that time of night?

MICHAEL (Groaning) An ambulance….

DEXTON Look, for the last time—are you going to help him?

POLICEMAN 3 Just answer the questions.

DEXTON Look, we’re not the bloody criminals – they set on us, they knifed our mate. Why all the questions?

POLICEMAN 3 Just answer the questions.

DEXTON All right, we were coming home from the disco.

POLICEMAN 3 A likely story.

DEXTON It’s true for Christ sake, it’s true.

POLICEMAN 3 I don’t want no lip from you Sambo. Now, what street did this happen?

DEXTON This street.

POLICEMAN 3 What street’s this then?

DEXTON Stoke Newington High Street – you bloody well know! Now phone the bloody ambulance.

POLICEMAN 1 (Stepping from behind the desk with Policeman 2) Who do you think you’re bloody swearing at? Up against the wall!

GEORGE Leave him alone!

POLICEMAN 1 You too, up against the wall! (The two policemen throw Dexton and George up against the wall.)

LEROY Look—our mate, been knifed, and you’re not doing nothing to help him.

POLICEMAN 3 There’s nothing wrong with him, just a bloody scratch—you can’t have us on.

TONY Well, let’s phone for an ambulance, then.

POLICEMAN 2 Look, the quicker you tell us what happened, the quicker your mate will see a doctor.

DEXTON That’s bloody blackmail.

POLICEMAN 2 Well, I’m using it on the right people then, aren’t I?

POLICEMAN 3 So where were you when he got stabbed?

DEXTON We’ve said already—Look, can’t you see he’s getting weaker?

POLICEMAN 3 Have you even been in trouble with the police before?

DEXTON I told you- I was picked up on SUS once.

POLICEMAN 3 Ah-well that throws a different COLOUR on it, then, doesn’t it? So you could have been out nicking tonight for all we know.

Michael does a terrible scream, followed by low groans.

DEXTON For Christ’s sake, can’t you see the blood on the floor?

POLICEMAN 3 All right Jack—phone for the ambulance.

Policeman 1 phones. The action freezes.

NARRATOR The boys were interrogated for ten minutes by the police before they called an ambulance for Michael. It took another fifteen minutes for the ambulance to arrive. All this time Michael’s condition was getting worse and his blood was dripping on the floor.

Action unfreezes.

GEORGE Look—can we phone Michael’s mum to tell her what’s happened?

POLICEMAN 1 No telephone calls!

DEXTON Look, come on man, all our mums will be worried sick.

POLICEMAN 1 Are you deaf? I said no telephone calls, do you hear?

LEROY Look, it’s our right to let our parents know what’s happened to us.

POLICEMAN 1 Sonny—you black bastards have got no rights in this country. Just shut up.

Enter two ambulancemen with a stretcher.

DELROY Christ, what kept you—look at our mate.

AMBULANCEMAN 1 Come on, get out of the way. Let’s see him.

AMBULANCEMAN 2 Got him Bill? Okay, let’s have him.

Michael is put onto the stretcher, stiil groaning. The other boys move as if to get into the ambulance with him.

POLICEMAN 1 Where do you think you’re going?

DEXTON We’re going with him to the hospital.

LEROY Yeh—he’s our mate, we want to go in the ambulance with him.

POLICEMAN 3 Oh no you don’t! You’re staying here, I’ve got some more questions for you lot.

DEXTON All right—then let just one of us go then.

POLICEMAN 2 Sit down Sonny—you’re staying here, you’re not going anywhere.

DEXTON For Christ’s sake, he’s our mate! We can’t leave him alone.

POLICEMAN 2 All of you! You’re staying here with us for the night.

POLICEMAN 3 Yeh, you’re holding your mate up now, aren’t you? I thought you said he was bleeding to death?

POLICEMAN 2 (To the ambulanceman) All right, take him away.

The ambulancemen take out Michael as the boys look on. The Action freezes again.

NARRATOR It took 45 minutes for the ambulance to reach the hospital which was only a few minutes drive away. Michael was dead when he arrived at the hospital.

Who killed Michael Ferreira?

End of Scene 2.

SCENE 3 Leroy and Tony’s House

It is 7.15am. Mr and Mrs Daniels are eating the. breakfast. They are both very worried.

Leroy and Tony enter, puffed out.

MR DANIELS Where the hell have you been? Your mother’s worried sick. (He stands up at the table).

MRS DANIELS Boys, I was so sick worrying about you.

MR DANIELS Look-it’s breakfast time. You could have been knocked down, robbed, dead on the streets-how were we to know?

MRS DANIELS I was going to phone the police about you.

TONY Sorry mum, look day, it’s a long story—but to cut it short, Michael got stabbed by a white boy last night, and we’ve been in Stoke Newington police station all night.

MR DANIELS What did you say?

TONY And we only went in there to phone for an ambulance for Michael.

LEROY And they wouldn’t even let us phone you up, or Michael’s mum.

MRS DANIELS What…. Michael stabbed?

LEROY And they kept him in the police station for ages before they called an ambulance.

MR DANIELS Have you told Michael, parents yet?

TONY No—Dexton was going to go round there, but he’s dead scared to go.

MR DANIELS Did you say they kept him there bleeding without even calling an ambulance?

The action freezes

End of Scene 3

SCENE 4 Outside the Mortuary

Mr and Mrs Ferreira are waiting to see the body of their son.

ATTENDANT (Opening the door) I’m sorry, but you can’t come in.

MR FERREIRA Look, we want to see our son’s body, that’s all.

ATTENDANT Well, you can’t come in. The coroner said that no one, only the police, can see the body yet.

MRS FERREIRA (Passionately) I want to see my son…. please let me see my son.

ATTENDANT I’m sorry madam, I can’t let you in.

MRS FERREIRA I brought him into the world-now I can’t see him now he’s dead?

POLICEMAN 1 (Entering) Move along please, we don’t want any more disturbances here.

MR FERREIRA You’ve got our son in there. We want to see him!

POLICEMAN 1 Well you can’t, now move along home or have to nick you for obstruction. (He tries to take Mrs Ferreira’s arm.)

MRS FERREIRA Don’t you touch me! You were the ones who killed my boy. You’ll never hear the last of this.

POLICEMAN 1 You don’t know what you’re on about, you blacks are all the same.

MR FERREIRA You! Racist! Listen to me—we’re going to get all our people together and we’re going to fight your dirty racism! We’re as much a part of country as anyone.

MRS FERREIRA We’ll make a movement to help all the black people, and we’ll clear racism right off the streets of this country!

The action freezes.

End of Scene 4

EPILOGUE

THE NARRATOR reads his final poem:

The boys were coming home,

They had been to the disco

in Stoke Newington—

Delroy, Gocrge, Leroy, Tony, Michael and Dexton.

Along came the blokes

looking for trouble

The racists jeered and insulted,

They crossed the road and used the knife,

the lethal weapon

which took poor Michael’s life.

The thugs shouted ‘Let’s run!’

Poor Michael

He was bleeding but nothing could be done.

His friends took him to the police station,

the cops kept him there—

against his will

as if he was the criminal,

as if they were pulling his hair.

They kept him there for quite a bit—

they treated him like shit.

They killed that kid

just like the police in Ireland,

or Hitler with the yids.

The ambulance took half an hour,

the ambulancemen could have been having their dinner

or taking a shower.

By this time he’d lost a lot of blood,

they said they did all they could.

Michael is gone now

but we’ll remember him.

We hate the one who killed him-

he’s a slut.

After this, there’s no turning back,

Black and white unite

and together we will fight!

To stop these rats from roaming the streets.

THE END