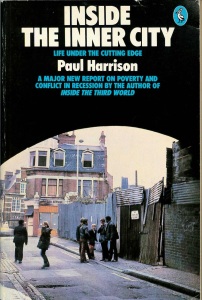

Below is an eyewitness account by journalist Paul Harrison on disturbances in Hackney. This is followed by some reports from Hackney People’s Press about the riot and its aftermath.

Harrison tries to be even-handed about the police throughout the book this is taken from, even spending some time with them on the beat as part of his research. The police’s side of the story was believed by fewer and fewer people throughout the eighties. The credibility of cops at Stoke Newington police station was severely undermined in the 1990s after numerous exposés by Hackney Community Defence Association and the police’s internal investigation “Operation Jackpot”.

But before the written account, here is a brief bit of oral history about the beginning of the riot by anti-racist campaigner Claire Hamburger, including an amusing anecdote about the non-rioting community and the police:

THE ROUGHEST BEAT: POLICING THE INNER CITY

Paul Harrison

The peacemaker gets two-thirds of the blows.

He who lights a fire should not ask to be protected from the flames.

Arab proverbs

In 1981 a Conservative government that had promised a strong approach to law and order presided over one of the most serious breakdowns in law and order in mainland Britain of this century.

On 10 April, the first Brixton riots erupted. On 3 July came disturbances in Southall, followed in rapid succession by major troubles at Toxteth in Liverpool, Moss Side in Manchester, and again in Brixton. There were smaller-scale disorders in Bristol, Southampton, Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Bradford, Halifax, Leeds, Huddersfield, Blackburn, Preston and Teesside, and across London from Acton to Walthamstow and from Haringey to Clapham. The list was a catalogue of Britain’s inner cities, finally forcing themselves dramatically into the nation’s consciousness.

Hackney, too, had its say. The year had already seen the earlier emergence of an ominous phenomenon of law-breaking by large groups of black youths. On 20 April, towards the end of a bank-holiday fair at Finsbury Park, hundreds of youths went on the rampage with sticks and bars, smashing up stalls and mugging people.

On the night of Tuesday, 5 May, about a hundred youths, most of whom had just come out of Cubie’s, the popular Afro-Caribbean disco off Dalston Lane, gathered round while some of them ripped out a jeweller’s window and stole jewellery worth £500. The retreating crowd threw bottles at the police.

In the early hours of Wednesday, 24 June, gangs of youths roaming the streets, again after chucking-out time at Cubie’s, smashed the windows of a travel agency and a fish-and-chip shop, grabbed the till of Kentucky Fried Chicken on Kingsland Road, and mugged three pedestrians.

Part of the problem was that London Transport bus crews, fearful of trouble, had been refusing to pick up passengers from Cubie’s for some months, thus leaving large gangs of black youths to walk home, along streets lined with shops, in a mood of anger and frustration.

It was not until Wednesday, 8 July, that the first attacks on police occurred [apart from chucking bottles at them on 5th May? Ed]. That night two officers on patrol in Stoke Newington were stoned [insert joke here about Stoke Newington police and drugs – Ed] and towards midnight four police cars were damaged by missiles. The next evening, police were out in force, on foot, in the Dalston area, keeping a couple of hundred youths on the move. Five shop windows were smashed and one policeman injured by missiles.

The worst disturbances occurred on 10 July. The location: the junction of Sandringham Road and Kingsland High Street. There was a certain inevitability about the site. Sandringham Road leads down into the heart of some of the worst private rented housing and the densest settlement of people of West Indian origin in Hackney. At the top, on the left, the Argos showroom windows gleam with consumer products. On the right, Johnson’s cafe, a haunt favoured by young blacks, the scene of frequent drug busts and raids in pursuit of ‘dips’ (pickpockets) escaping from their favourite hunting-ground of Ridley Road Market (a quiet back alley, Birkbeck Road, leads between Ridley and Sandringham). At the junction of Sandringham and Kingsland, there are permanent pedestrian barriers lining the road, offering support and, if necessary, shelter against attack.

Johnson’s Cafe, Sandringham Road, from the 1976 UK reggae documentary “Aquarius”

The trouble that day began around 5 p.m. when a group of youths robbed a jewellers’ shop in Kingsland High Street. The police closed down Johnson’s cafe and moved on groups that formed outside: a few bricks and bottles were thrown. Then larger groups of blacks began to congregate. At around 7.30 p.m. two fire-bombs were thrown: one at the Argos showrooms, followed by looting; and one at a policeman in Arcola Street, site of the main social-security office in Stoke Newington. The police charged down Sandringham Road, but were pushed back by the youths for a distance of about 40 metres before making a successful counter-charge. Just before midnight bricks were thrown at the police stationed at the mouth of Sandringham Road, from the barrier railings outside the Rio cinema, opposite. Under attack, exhausted from working days of fourteen and sixteen hours around London’s riot areas, some officers lost their cool. A unit of helmeted police charged across the road, truncheons drawn, and used them to `disperse’ the crowd at the railings. One girl suffered a head wound and was rushed to hospital.

I arrived on the scene just after midnight. There was an atmosphere of Sweeney and Starsky and Hutch. It was just after the stoning incident, and police Rovers, Escorts and blue-and-white vans packed with men were using Kingsland Road as a race-track, hooters wailing and lights flashing, in pursuit of the suspected assailants. For the meanwhile, the protection of property took a back seat, and I watched for half an hour as menswear shop, Mr H, was looted down to the last button and buckle. The window smashed a few seconds after I had walked past it: there was no one in sight but a young black boy of about thirteen, looking a picture of innocence. A few minutes later five or ten youths, black and white, began to arrive, clambering over the railings from the road, then leaning against them and looking around themselves with great caution before acting. One boy set the example, snatching a white sweatshirt and stuffing it down the front of his jacket. The others helped themselves, each one walking away in a relaxed manner calculated to allay suspicion. Mr H’s alarm was ringing noisily: but so were many others. After a lull more wardrobe hunters arrived, and some of the first wave returned for second helpings. The first time they’d snatched anything that came to hand. This time they were more discriminating, checking sizes and colours and discarding unsuitable ones.

Three whites in their late twenties stood opposite, smiling benevolently and shouting ‘Police’, with the accent on the first syllable, whenever men in blue came near. A skinhead in a long Edwardian jacket, attracted by the Victoria Wine off-licence next door to Mr H, wrapped a brick in a paper bag and hurled it at the window with all his might. It bounced off. A boy slipped on the glass outside Mr H, and cut himself badly, and the others gathered round to help. The looting proceeded, while at the back, thieves were smashing their way through security bars and looting the racks inside. Some of the earliest looters had the opportunity to saunter by five or six times, while the skinhead persisted in his increasingly desperate attempts to smash the off-licence window, the only effect being to leave a dusting of brick powder on the glass.

At about 1 a.m. a big black bearded youth in a long leather raincoat took out a pair of model legs from the window and threw them into the middle of the road. Police vehicles had passed the scene at least forty or fifty times, but this act finally attracted their attention. A van screeched to a halt, a dozen officers leapt out, and one of them stayed behind to stand guard over what, by now, was a totally empty window.

The whole evening had been, by the standards of Brixton, Toxteth and Moss Side, a mere affray, but it was a disturbing pointer to what could happen when police attention was diverted and the thin veneer of ice that caps Hackney’s troubled waters was cracked. In all forty premises were damaged that night and sixty arrests were made. The score of injuries was even: twenty-three police, twenty-three members of the public.

High Noon in Dalston

The following day, Saturday, 11 July, far worse was expected. Shoppers stayed away from the High Street and the Wimpy Bar owner complained of his worst Saturday for business in twenty years. But the shopkeepers had their minds preoccupied in other ways. From Dalston Junction to Stamford Hill, they were measuring and sawing, drilling and screwing, fitting and hammering. According to means, great panels of corrugated iron, wood, plywood, chipboard, hardboard and cardboard were being battened up by those who did not already have armour-plated glass, grilles and shutters. Builders’ merchants were running out of supplies, security firms doing more business than they could cope with, employees and friends and relatives were dragooned into a frenetic race against time to put up their protective walls before the expected confrontation of the late afternoon and evening.

The media came sniffing for trouble. One camera crew arrived and interviewed people on the street. Another crew filmed a festival at London Fields where trouble had been predicted. People threw darts at images of Thatcher, drum majorettes twirled, and the Marlborough pub heavies won the tug-of-war match. But there was not a stir of trouble. When one of the organisers phoned the television company to ask why the festival had not been televised, she was told it was because ‘nothing happened’.

Up at the end of Sandringham Road, the atmosphere was High Noon. The police were scattered, in twos and threes, all down the High Street. About fifty black youths, with the merest scattering of whites, were sitting along the railings and on the wooden fence of the petrol station and crowding outside Johnson’s cafe. I talked to many of them and the grievances bubbled out, against unemployment, racialism, but above all against the police.

A pretty girl of seventeen, with four grade ones in the Certificate of Secondary Education, out of work for ten months, said:

‘I go down the temp agency every morning. There’s only been two jobs going there all week. Since Thatcher’s come in, everything’s just fallen. She needs a knife through her heart.’

Her nineteen-year-old friend continues:

‘I got three O-levels and that’s done me no good at all. A lot of my friends are having babies. If you haven’t got a job, you might as well have a baby.’

Vengeance for colonialism and slavery, rebellion against discrimination, redress for police abuses, all mingled together as a group of boys pitched in. They were angry, agitated.

‘You can’t win,’ said a tall youth worker:

‘If a black person drive a nice car, the police say, where you get the money to drive that? You wear a gold chain, they say, where you thief that? We like to gather in a little place and have a drink and music, so what the police do? They like to close it down, so we all on the street instead. And what happen when they get hold of you? They fling you in the van, they say, come on you bunnies [short for ‘jungle bunnies’]. They play find the black man’s balls. They treat us like animals, man, they treat their dogs better than they treat us. They kick the shit out of us and put us inside to rot. They think they are OK in their uniforms. But if that one there was to walk over here naked now, we’d kick the hell out of him. Somebody said, black people will never know themselves till their back is against the wall, well, now our backs is against the wall. I’m gonna sit right here, and I ain’t gonna move.’

A boy of eighteen in a flat corduroy cap said:

‘I was driving down from Tottenham to Hackney once, I got stopped seven times on the way. Four years ago, they came to my house searching for stolen goods and asked me to provide a receipt for everything in my house. We’ve been humiliated. It’s time we show them that we want to be left alone.’

‘We’re fighting for our forefathers,’ said the seventeen-year-old secretary:

‘We’ve been watching Roots [the film series on American slavery]. They used us here for twenty years, now they got no use for us, they want us out.’

An eighteen-year-old boy in a green, red and black tea-cosy hat went on:

‘The police can call you a fucking cunt, but if you say one word at them they’ll take you down. They don’t even like you to smile at them. You try to fight them at court: you can’t fight them, because black man don’t have no rights at all in this country.’

There was a lot of military talk, for this was not seen as a challenge to law, but a matter of group honour: the police, as a clan, had humiliated young blacks, as a clan, and clan revenge had to be exacted.

‘Since they got these riot shields,’ said a boy of twenty, ‘they think they’re it. We can’t stand for that. Tonight we have to kill one of them, and now there’s a crowd of us, we’re gonna do it. If they bring in the army we’ll bring in more reinforcements and kill them.’

One boy in sunglasses, sixteen at the oldest, launched into a lecture on guerrilla tactics:

‘If you come one night and they make you run, then the next night you bring enough stones, bottles and bombs that they can’t make you run: you don’t run, they run.’

He smirks, as if he has just stormed their lines single-handed:

‘But look at everyone here. They’re all empty-handed. Last night they were wasting their petrol-bombs, throwing them on the street. It’s no use throwing one without a specific target. Look at that police bus: one bomb at the front, one at the back, and that would be thirty-two or sixty-four police less. You got to have organisation, like they got.’

There were moments of humour, too. One drunken man in a leather jacket was straining to have a go at the police. ‘What can you do?’ his girlfriend asked him, holding him back by the jacket.

‘I can at least fuck up two of them. I can take the consequences. They ain’t gonna kill me.’

‘They will kick the shit out of you,’ says his girl-friend. She pacifies him for the moment, but he eludes her and stands, slouched on one elbow, against the railings, awaiting his moment of glory. Levering himself up he staggers half-way across the road towards the main police gathering, shouting, ‘You’re all a load of fucking wankers.’ Before he has got five metres he is arrested by the district commander in person.

In the end, the brave talk remained talk. At 6 p.m. the police decided to clear the crowds that had assembled. They moved on the group on the petrol-station fence, pushing them down Sandringham Road. At the same time another cordon of police began to walk up Sandringham Road from the other end. An escape route was deliberately left open — the alley of Birkbeck Road — and the cordons let through most of those who wanted to get by.

But many of the youths believed the police had trapped them in a pincer with the intention of beating them up. Several of them started to break down the wall next to Johnson’s café to use the bricks. As one young boy explained:

‘When they come smashing you over the head with a baton one night, the next time you know you’ve got to get something to defend yourself with.’

But this misinterpretation of police intentions itself brought on the attack it was intended to prevent. The police closed in to forestall the brick-throwers, there were scuffles, one policeman was injured, and five arrests were made.

And that was it. The expected explosion did not occur. The proceedings ended not with a bang but with a whimper. It is perhaps typical of Hackney that, although more deprived than Lambeth and most of the other scenes of disturbance, it couldn’t get together a full-blooded riot. The reason lies in Hackney’s fragmentation: it has no single core like Brixton has, where blacks predominate and congregate, no ghettos without their admixture of poor whites, Asians and Mediterraneans. The sheer numbers required to start a large-scale disturbance never came together. Police tactics, too, were flexible and effective: with the experience of Brixton to learn from, they did not offer a static, concentrated defensive line that was a sitting target for missiles. And they split up the opposition into smaller groups and kept them moving down separate side roads, preventing any larger crowds from forming.

Nevertheless, there was rioting and there was looting and there was violence. It is important to understand why. These were not the first skirmishes in the revolution, nor were they an organised protest against monetarism or mass unemployment. Many of the rioters were at school, some had jobs. The conscious motivation of those who were not just in it for the looting was, quite simply and straightforwardly, hatred of the police among the young and the desire to hit back at them for humiliations received. Monetarism and recession were, however, powerful indirect causes. The strains produced by loss of hope and faith in a society that seemed to have lost all charity certainly provided emotional fuel for the troubles. More specifically, recent recessions, each one deeper than the last, pushed up levels of violent theft and burglary, and therefore led to a greatly increased pressure of policing in the inner city, bringing police into unpleasant contact with increasing numbers of whites and blacks, guilty and innocent alike.

BLUE IS THE COLOUR: VIOLENCE IS THE GAME

Hackney People’s Press issue 71, August 1981

The clashes in Dalston and Stoke Newington between police and local people on the weekend of 10-12 July were the culmination of several days of tension, caused mainly by police tactics.

Local traders had been told repeatedly to board up shops because the police were expecting trouble, and this created an unreal siege-like atmosphere in both Kingsland and Stoke Newington High Streets. There were also a number of raids on Johnson’s, a West Indian cafe in Sandringham Road, which was to become the focus for the worst disturbances.

Our reporter was threatened by this policeman with getting his camera smashed. Shortly after, he was clubbed to the ground by another, and had to have stitches put in a head wound.

After groups of youths had gathered on various street corners police presence in the area was increased dramatically throughout the week. Trouble became inevitable when the police tried to prevent people going down Sandringham Road, to gather outside Johnson’s. On the Friday night, there were at least two baton charges by police to clear Sandringham Road. Policemen were lashing out wildly with truncheons – aiming at the head, in direct contravention of the Metropolitan Police Standing Orders – and many people were injured, including a Hackney People’s Press reporter, who was standing in the doorway of the Rio Cinema. He was taken to the Hackney Hospital, and had three stitches in a scalp wound. Our reporter writes:

“The casualty ward of the hospital was like a battle-field. A number of people were being treated for head wounds. I spoke to two 16-year old white youths who had been attacked. One of them had been truncheoned and kicked while outside the Rio, at the same time as me. Another had been attacked with a group of friends while on his way home to Stoke Newington. With his head bleeding from a wound, he and his friends walked all the way from Sandringham Road to Hackney Hospital. While at the hospital I saw uniformed and plain-clothes police writing down the names and addresses of people being treated. They were being helped to do this by at least one member of the administrative staff.”

In Stoke Newington on the same night there was repeated use of violent police tactics to clear the streets of people, many of whom were innocent bystanders and spectators. Several times Transit vans full of police were driven very fast down narrow roads and up onto pavements. Coachloads of police would suddenly rush out of their buses and chase off local people, lashing out wildly with their truncheons. HPP knows of a number of people who were attacked and arrested on that evening.

In most of these cases criminal charges are now pending, which makes any comment on them at the moment difficult, but it is quite clear that random attacks and arrests were being made, on the assumption that anyone around on the streets deserved what they got. On the Saturday, there were further disturbances during the afternoon, particularly in the Sandringham Road area. A pincer movement by police to try and clear the streets led to further violence and a number of arrests. Residents of St. Mark’s Rise were disturbed during the afternoon by groups of police chasing youths through their gardens. In one incident the police commander himself, Commander Howlett, arrested a man outside the Rio Cinema, during a conversation with a Hackney Councillor and the Secretary of the Hackney Council for Racial Equality. The man has now been charged with insulting behaviour after he had shouted at the group of people talking.

By the Sunday, the situation was a lot calmer, but there was still a massive police presence on the streets. Coachloads of them seemed to be permanently parked in Sandringham Road, and a new style of Transit van, with iron grids over the windscreen to prevent it being smashed, was seen outside Stoke Newington police station.

The organisers of two local festivals held that weekend at London Fields and Stoke Newington Common, were asked by the police to cancel their festivities. Both of these refused and, of course, there was no trouble at all. Since that weekend the inquests have started. A Hackney Legal Defence Committee has been set up and has started helping those arrested and attacked by the police during the various incidents. Already more than 50 people have been contacted by the Committee, most of whom will appear in court during August. The Borough Council, Hackney Council for Racial Equality and Hackney Community Action have all come forward in condemning police behaviour on Hackney’s streets that weekend. Below we report on a number of these initiatives. [an article on proposals for community control of the police, not included here – Ed]

UPRISING AFTERMATH

Hackney People’s Press issue 72, September 1981

Over 100 people were arrested after the uprising in July when youth took to the streets and clashed with the police. Many of them have now appeared in court, and some very severe sentences have been imposed by the magistrates. The Hackney Legal Defence Committee (HDLC) has been set up to assist those arrested during the uprising. Below we summarise what they are trying to do. First, we print an account of some reactions in the month following the uprising.

Along Kingsland and Stoke Newington High Streets, local traders were still repairing damage done to shops. I called in at Johnson’s cafe in Sandringham Road and asked about the baton charges and damage done to the West Indian cafe. I was told:

“All the glass wall and glass door at the front of the shop was kicked in, kicked in by the police – bash! and smash!”

Not doubting the fact that the police had lashed out wildly, zooming with their batons and cracking scalps, I said: “What’s your opinion of the riots that took place between the black youths and the police in the Dalston area in July?” The woman in the cafe said:

“Police came into the cafe using truncheons, slashing them in…a them head, using all their strength in murderous attacks on defenceless people. They was not concern about the frighten state of the people’s mind.”

I asked if there had been anything missing or stolen. She exclaimed: “No. Blood! Blood! Spilled by police tactics. They batter them, batter them in a tha head.”

Then I interviewed two administrative officers at the Town Hall, Mare Street. They suggested that the local authorities hadn’t any direct links with the action and movement of the local police force. They are only concerned in the parking sector and community work, and have a liaison committee with the police.

Nonetheless, I thought these questions were vital. At the time of the Civil Service dispute, the Town Hall was relied upon to share the work to help the unemployed. So I continued to ask their opinion on the riots and terrorism people suffered by the serious violence inflicted by the troops of armed police leaping from their vans, causing breach of the peace with unnecessary provocation.

One said:

“The government, in general terms, is giving the local authorities less and less money, therefore their plans for central facilities on programmes for work become fewer.”

He added:

“The riots in Hackney are minor compared with, say, Manchester or elsewhere.

“The disturbances should not cause great alarm, with the number of people who were involved. The local authorities are presently having committee meetings regarding additional educational courses. Benefits may be gained from self-organisation.”

I approached Stoke Newington Police Station enquiring about the clashes and police tactics, and asked to talk to the local home beat officer informally. I was told to write to the superintendent of police. Hercules [“Hercules” being the pseudonym of the reporter – Ed]

HOW YOU CAN HELP THE HACKNEY LEGAL DEFENCE COMMITTEE

If you are one of the arrested and require legal or financial assistance, or if you are a witness to any arrest or have any information which would help us in the legal defence of those charged, or if you received any injuries (or witnessed anyone receiving injuries) or have photographic evidence which would assist in our work, please contact us immediately at the address below.

We need financial contributions to pay for legal costs and fines, to ensure the best possible defence.

HLDC also needs your active participation in visiting courts and collecting information from those charged, those who witnessed incidents, those who were beaten up, etc.

If you want to contribute to the work of HLDC or require any further information, con-tact us at: The Co-ordinator, Hackney Legal Defence Committee (HLDC), c/o 247 Mare Street, E8; tel 986 4121.

HLDC meets every Friday evening. Contact the above for further details.

Finally, there is a suggestion on the Hackney Buildings site that the Hackney Peace Carnival mural was partly inspired by the riots of 1981, presumably including our own riot around the corner…