Towards the end of the 19th Century, Elijah Sherry founded a timber business, initially dealing in dockyard off-cuts before opening a timber yard in Bethnal Green. The family business rapidly expanded and in 1912 “bought a site along the Hackney Cut at Homerton Bridge, kitted out with a new steam and electric plants – including band mill, sawmill, planing and mould mill.” This site closed in 1970 after a series of mergers.

Sherry’s Wharf Estate

In 1972 the land was acquired by the Greater London Council (GLC), who redeveloped it into an estate of 143 maisonettes with gardens. Of these, 43 were specially adapted sheltered flats for the elderly. This new estate was finished in early 1981 and overlooked Hackney Marshes and the River Lea. (I am unclear if that was desireable in 1981 or not – leave a comment if you know more!)

Residents in the adjoining and delapidated Kingsmead Estate were originally promised first refusal for the new flats by the Labour-controlled GLC. Including several pensioners who were looking forward to the new sheltered accommodation.

But there was a change of heart in May 1977 when the GLC became controlled by the Conservatives. With typical greed, the tories decided instead to put the new flats up for sale with a minimum asking price of £30,000 (£233,595 in 2024 money).

This did not go down well with local people, who protested the GLC into a minor climbdown: Some of the flats would be rented out at between £22 and £37 a week – a figure astronomically higher than the council rents of the time. New tenants were vetted by the GLC and expected to be on a wage of at least five times their rent. There is a fairly transparent agenda here to reserve the new estate for wealthier, more “respectable” people.

Protest!

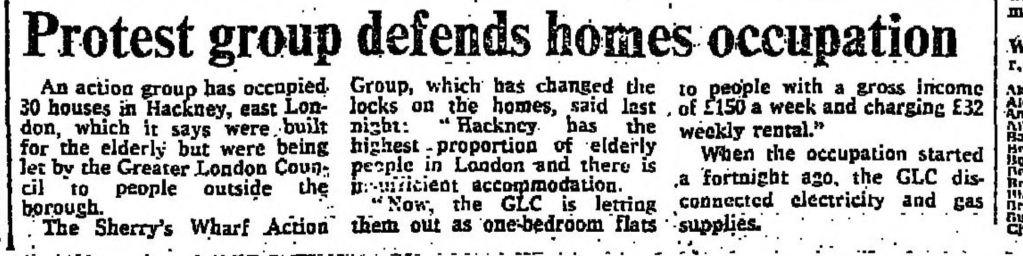

Around 50 of the flats were rented out. But then, at 1:30am on the 1st of February 1981, 200 people squatted 30-50* of the properties in Sherry’s Wharf in protest against homlessness in London and against the sell off.

(*Some accounts say 30 and some 50).

Immediately after the occupation, a leaflet was distributed round the Kingsmead Estate to explain to tenants why the flats and houses were being squatted.

The squatters have also drawn up a charter of basic aims, to be agreed by everyone living there. These include taking care of the flats and houses and of the lawns and pathways on the estate, and respecting the rights and property of fellow squatters.

Regular meetings are held, attended by representatives of all the flats ana houses, and organisational tasks are shared out.

Hackney peoples press

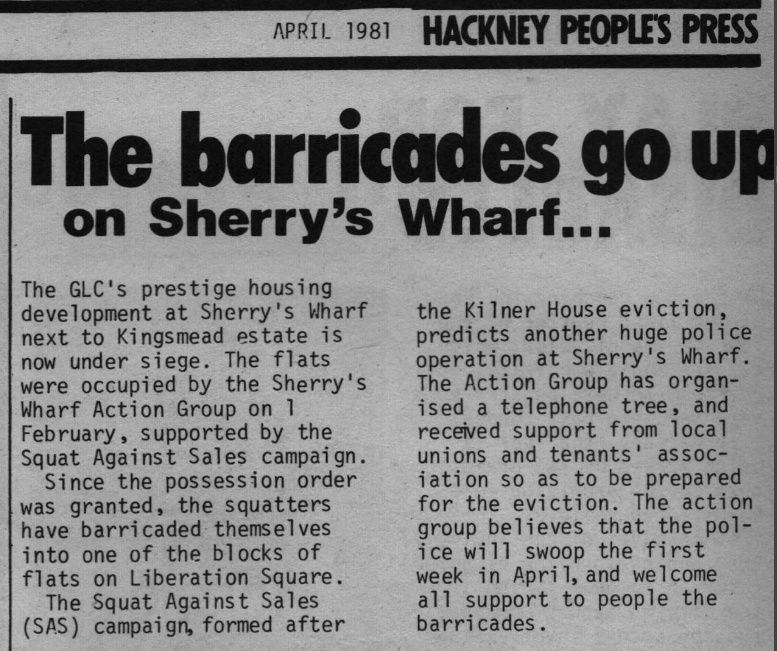

The squatters included local people organised as Sherry’s Wharf Action Group supported by activists from Squat Against Sales, who had recently been involved with an occupation of Kilner House in Kennington which was evicted in January 1981 by 600 cops from the notorious Special Patrol Group.

Hackney Peoples Press reported on the occupation and its demands:

That the sheltered accommodation should be restored and returned to the local pensioners for whom it was intended;

and that the rents on the estate should be reduced in line with the rest of Kingsmead Estate, and the income qualification removed.

The occupation has a third aim: to draw attention to the worsening problem of homelessness in London.

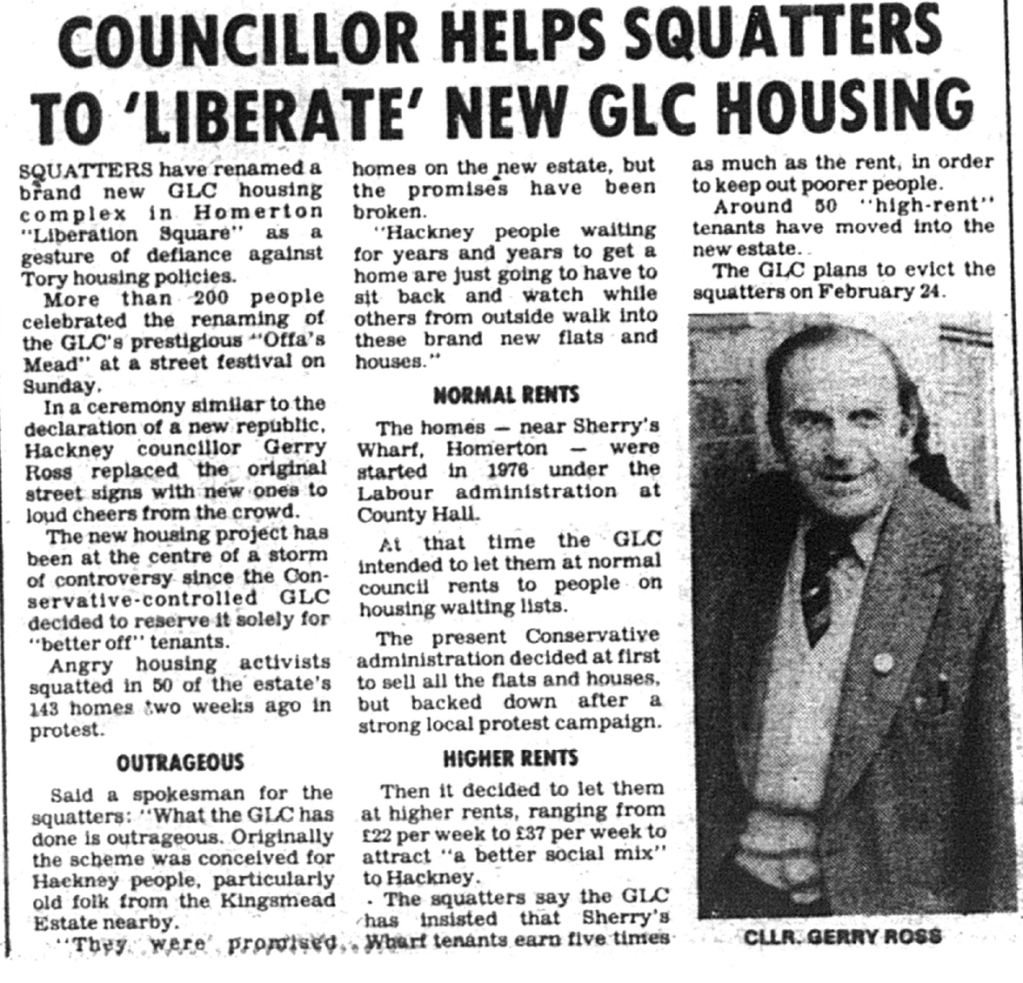

A street party was held on Sunday 15th February 1981 – opened by Hackney GLC Councillor Gerry Ross (Labour). About 200 people attended:

entertainment was provided by Smiley the Clown and local young musicians; there was play equipment for children, and local people got the chance to look round the flats and houses which had been intended for them.

Hackney peoples press

During the party the Offa’s Mead block / area of the estate was renamed “Liberation Square” with new signage. (See photo above). This all generated some decent press coverage.

But by April, the squatters were predicting a mass eviction, and according to Past Tense this came to pass on 17th April 1981.

The Labour Party regained control of the GLC in May 1981, heralding the era of “loony lefty” Ken Livingstone. This supposed municipal socialism does not appear to have made any difference to the situation at Sherry’s Wharf.

In May 1982, the anarchist newspaper Black Flag published some terrible poetry commemorating the protests:

Today!

The story of Sherry’s Wharf in the late 20th Century is the story of London in microcosm. It begins with the deindustrialisation of the river, followed by a move to residential use of the land, in which existing residents are priced out…

In 2018 the Hackney Council bought the freehold on the Sherry’s Wharf land from the Canal and River Trust.

Section 144 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 made it a criminal offence to trespass in residential properties with the intention of living there… But all is not lost!

Some handy insights from the always excellent Advisory Service for Squatters:

If people are squatting in a clearly residential property, they risk arrest and so losing their home, but it does not cover all situations. The law DOES NOT cover situations where:

• the property is not residential, people are or were tenants (including sub-tenants) of the property,

• people have (or had) an agreement with someone with a right to the property,

• people in the property are not intending to live there (maybe merely visiting, holding a short term art project, a protest,etc.)

Notes For New Squatters

So despite what you’ve heard, it might be possible for protests like the occupation of Sherry’s Wharf to happen in London today.

And it’s needed now more than ever. Hackney has one of the highest rates of homelessness in the country. And everyone knows someone who is struggling to pay their rent.

Official organisations like Hackney Night Shelter struggle on, doing incredible work with little funding. It was brilliant to attend a Hackney Anarchists benefit for the homeless earlier this month too.

Meanwhile, a three bed flat in Offa’s Mead sold for £520.000 in 2019, which is £286k above inflation. Rental prices appear to be an immoral £2300 a month, but that, dear reader, is what you get after 43 years of local and national governments colluding in price gouging, property speculation and gentrification.

There isn’t a silver bullet to solve the housing problem (although musing on who to shoot is an increasingly enticing pastime). Fundamentally a home needs to be recognised as a human right rather than a commodity – and we won’t get there by blogging eh?

But the occupation of Sherry’s Wharf and the support this got from local residents shows us what is possible. Perhaps Liberation Square was shortlived and ultimately a failure as a protest. But it was followed by a huge revival of the squatting movement – with tens of thousands of people taking matters into their own hands and turning empty properties into homes.

As late as 1993 Hackney was still the number one borough in London for squatting. After this it became increasingy “desirable”, which meant evictions and spiralling rents.

We can’t bring those days back by dreaming about them, but we can keep the idea of free and affordable housing alive and feed that into current struggles. An insightul and fun (free!) document on the squatting movement of yesteryear is “Squatting is part of the housing movement: practical squatting histories 1969-2019”.

There is loads more to read on the history of squatting in Hackney in our housing/squatting tag.

More information and sources used