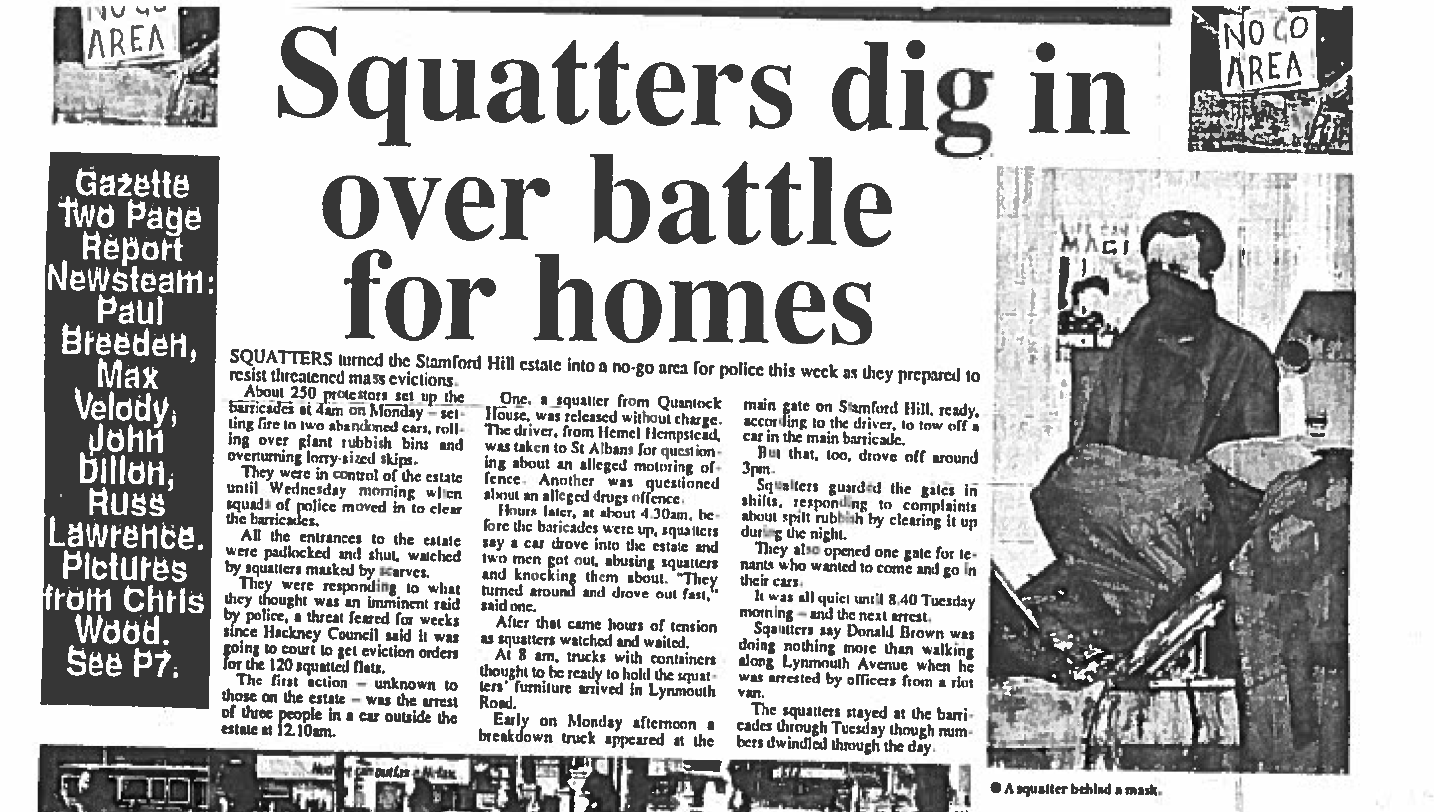

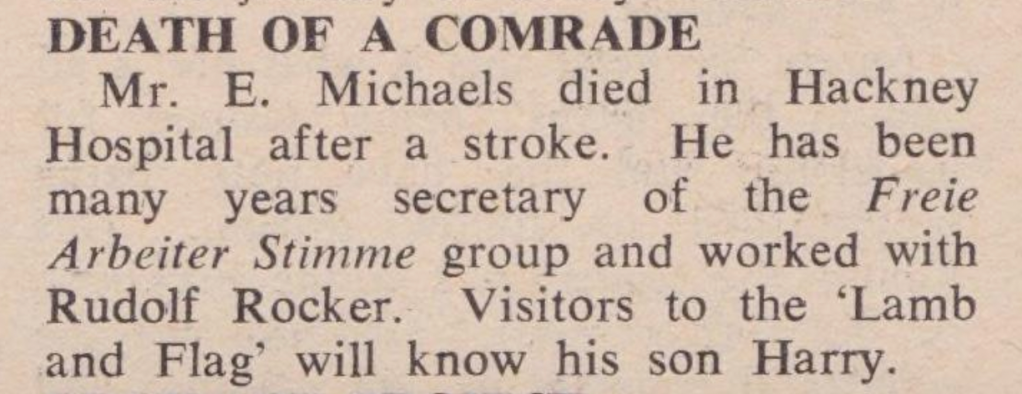

The obituary above appeared in Direct Action vol 7 #3, in March 1966. Direct Action was the newspaper of the Syndicalist Workers Federation, an anarcho-syndicalist organisation which operated from 1950 until the late 1970s. The SWF then became the Direct Action Movement before changing into the Solidarity Federation in 1994 – an organisation which is still active today.

Who was he? Everything starts with an “E.”

It’s easy to understand that a Jewish immigrant revolutionary might want to keep their personal details secret. Googling “E. Michaels” produces some good results in the anarchist archives, but that is only half of the story…

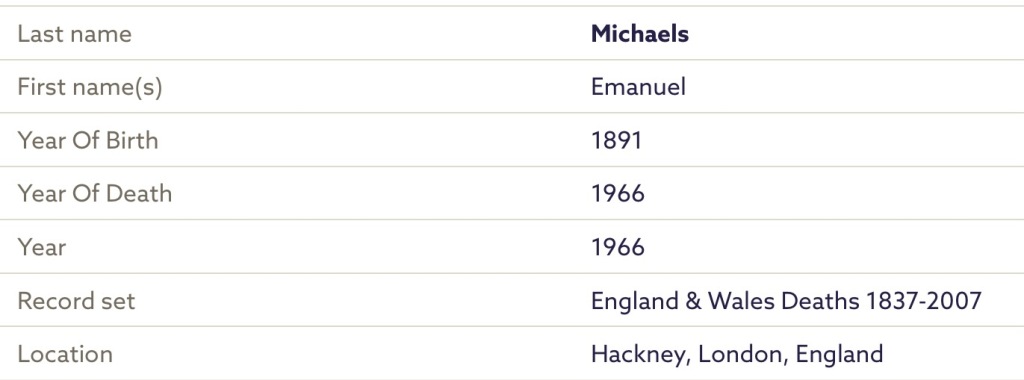

Fortunately there is only one “E. Michaels” listed in the death records for Hackney for 1966:

Further poking about turns up this lovely bit of genealogy, which suggests that Emanuel:

- Was born in Plock, central Poland on 25 Sep 1890 (near enough to 1891 listed above?)

- Emigrated to England at the age of ten in 1900.

- Married Rosie Kitman (3 Apr 1892 – 14 Jan 1963) at Mile End in 1914.

- Had four children (including Harry, as in the Freedom clipping above, which is reassuring)

- Worked as a Tailors Presser.

- Died 12 Feb 1966.

This seems to fit quite well with what we know from the obituaries above and the sort of lives that radical Jewish anarchists would be leading at this time. But I’m not an expert, so if any historians or genealogists out there have spotted any errors, let me know!

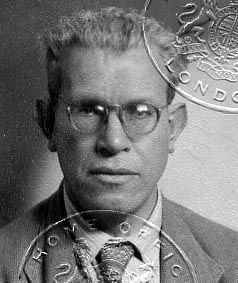

Update: a comrade has kindly supplied a passport photo of the handsome Michaels.

Anarchy in the East End!

Most of comrade Michaels’ political activity seems to have been in the East End of London in the first half of the 20th Century. He was involved with setting up a “free school” at 62 Fieldgate Street in Whitechapel, which also hosted The Worker’s Friend Club and the East London Anarchist Group. He was also the secretary of the prisoner support group the Anarchist Red Cross and is listed as a donor in a few issues of the London anarchist newspaper Freedom in the 1910s.

According to census data he lived at the following addresses too:

- 1911: 25 Hungerford Street, Commercial Road

- 1921: 73 Sutton Street

- 1939: 163 Jubilee Street E1

But what about Hackney, eh?

Michaels seems to have remained active up until his death. Sparrows Nest Archive has scans of some his letters from 1958 to 1964. Most of these are addressed to Ken Hawkes, the national secretary of the Syndicalist Workers Federation. Many of them mention meetings at Circle House, 13 Sylvester Path, E8. I’ve written about the Workers Circle and Jewish radicals in Hackney previously.

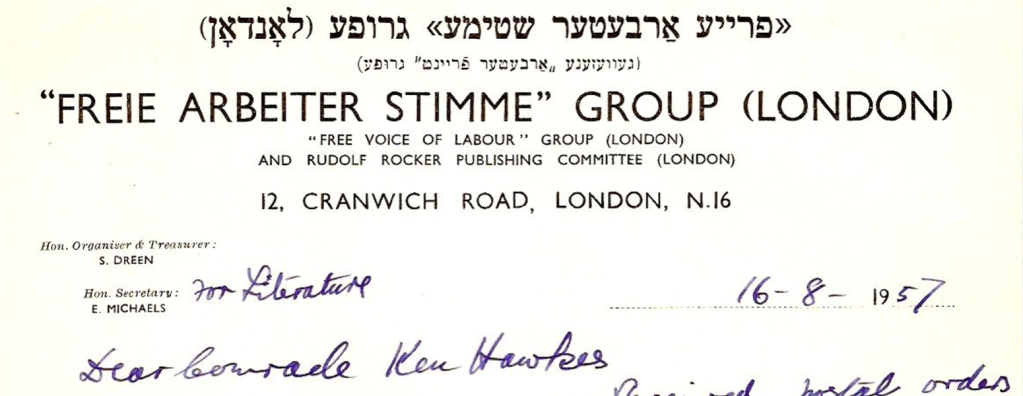

Michaels’ letters are largely administrative – donations, exchanges of publications, details of meetings etc. But the letterheads are invaluable:

Firstly, they tell us that Michaels was the Honorary Secretary of the Jewish radical organisations Freie Arbeiter Stimme (Free Voice of Labour) and Rudolf Rocker Publishing Committee. (Rocker was a German Gentile who became heavily involved with the Jewish anarchist movement).

Secondly, the letters show us where Michaels lived in Hackney. (This is my assumption, based on the nature of the addresses listed and that meetings etc seemed to take place at Circle House and not those on the letterheads). So it looks like Michaels lived at 12 Cranwich Road in Stamford Hill during the 1950s and then moved to “Morley House” N16 in 1961. Which no longer exists…

But! According to this useful blog, Morley House was one of the council blocks at the east end of Cazenove Road, Stoke Newington and was renamed Nelson Mandela House in 1984. There is a quote from Mandela on the side of it which can be seen here.

A diversion down Cazenove Road

According to Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, Morley House was built in 1937-1938 “with a meanly detailed exterior, although the planning of the individual flats was generous at the time”.

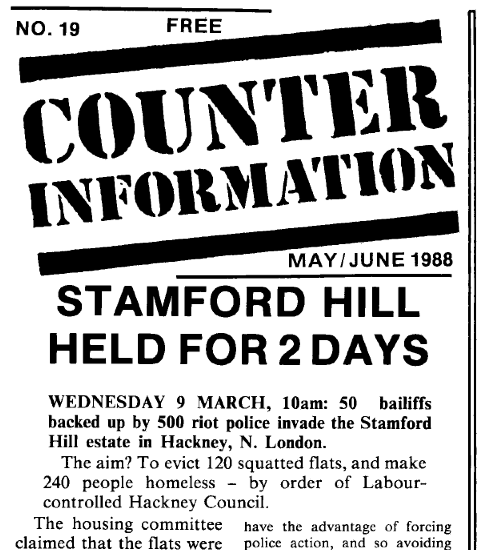

Fourteen years after Emanuel Michaels’ death, the flats and exterior would see further anarchistic action.

Hackney Peoples Press reported that Morley House was due for renovation, which meant that:

“All the council tenants were moved out between 1978 and autumn 1979, and the estate was left almost completely empty.”

Perhaps inevitably some tenacious local people seized this opportunity:

“In November 1979 the first squatters started to move in, even though vandalism and thieving had reduced the building to a dilapidated eyesore.

By February 1980 approximately 80 flats were occupied and some residents approached Hackney Community Housing Resource Centre to ask about licensing the house. (A licence to occupy premises does not imply tenancy as such but makes the occupation authorised by the Council.)

They suggested a direct approach to the Council, and three Council Officers were invited to visit the estate and talk to same of the residents. These officers submitted a report to the Housing Management Committee on 31st March this year, and suggested the granting of a license through Hackney Community Housing (HCH). The Committee however, rejected the recommendations and decided to evict the residents – offering the property to HCH as short term housing instead.”

What followed was a bit of a standoff, with the Council refusing to back down and the squatters getting more organised:

“They held weekly meetings, formed themselves into an Association, cleared up rubbish, and met a number of councillors to discuss the matter. They also formally presented a deputation to the Housing Management Committee asking once again for a licence.”

That all probably seems pretty amazing to people who’ve tried squatting recently, but even in 1980, this was simply delaying the inevitable:

Six months later, the Council’s heavy squad made the 200 squatters homeless:

“Following two dramatic dawn raids by police the Morley House squat in Cazenove Road has had all its electricity and gas supplies cut off. At least 25 people were arrested, mainly on charges relating to the stealing of gas and electricity, but the police indiscriminately smashed through the doors of all the tenants on two of the blocks on the estate.

The first raid took place on 14 January and was made by a large number of police, accompanied by police dogs and gas board officials. The police carried no warrants and yet made extensive searches for drugs and stolen goods. Many doors were broken down in the raid, while others had 6-inch nails driven into their hinges to prevent tenants from re-entering their flats. Whilst searching the rooms the police took many photographs, presumably to be used later in evidence.

Using the excuse that many of the tenants were not paying for gas, the supplies to the estate were cut off, although electric cooking rings were brought in by the Gas Board for those who complained that they were in fact paying their gas bills. But in the early hours of the following morning, the police arrived again, this time with Electricity Board officials, and electricity supplies were cut off under the pretext that all the wiring on the estate was in a dangerous condition.

As a result of these raids about half of the 150 people who lived in the squat have been intimidated into leaving. Speaking to residents of Morley House HPP has discovered that these raids follow several months of police harassment. It is estimated that some 50% of the residents had been picked up by the police prior to the raids. Morley House has been a licensed squat for over one year. In that time Gas and Electricity officials have visited the estate several times, but have not ordered any repairs.”

I hope that Emanuel would have approved of the squatters, but you never know. It’s interesting that the block was subsequently renamed Mandela House – Hackney Council in the 1980s was eager to promote social struggles thousands of miles away, but renaming the block after Emanuel Michaels or celebrating the courageous battle of the squatters was off-limits…

If anyone reading this has more information about either Emanuel Michaels or the Morley House occupation, please do leave a comment or drop me an email.

Sources and further reading

Special thanks to Neil Transpontine.

The Workers’ Circle – fighting anti-semitism in Hackney

Tom Brown – Story of the Syndicalist Workers Federation: Born in Struggle at Libcom, who also have an archive of the SWF’s Direct Action newspaper.

Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner – The Buildings of England: London 4: North, Yale University Press 1999.

George Cores – Personal recollections of the anarchist past (published by Kate Sharpley Library, available at Libcom)

Nick Heath – Echoes of Ferrer in an East End back street at Libcom

Albert Meltzer – The Anarchists in London 1935-1955. A personal memoir (online at Libcom, hardcopy from Freedom Press.)

Rob Ray – A Beautiful Idea: History of the Freedom Press Anarchists (Freedom Press, 2018)

Philip Ruff – Book Review – The Tragic Procession: Alexander Berkman and Russian Prisoner Aid, 1923-1931 (KSL/ABSC, 2010) at Kate Sharpley Library